“Dada Marshall and Propagandada” George Grosz and “Metapolitiker” Theodor Däubler: Metafisica and Politics in Berlin, 1920

Carlotta Castellani Carlotta Castellani Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

The aim of this paper is to investigate the relationship of the Berlin-based artist George Grosz and the eclectic poet and art critic Theodor Däubler with reference to their mutual interest in Italian modern art, from Futurism to Metafisica. Through the prism of their interaction, it is possible to follow the double fortune of Metafisica in Berlin in the year 1920 thanks to the intricate network of contacts and collaborations that, mostly through art magazines, facilitated the circulation of images by de Chirico and Carrà as part of a shared international visual culture, open to multiple stylistic and ideological interpretations.

The aim of this paper is to investigate the relationship of the Berlin-based artist George Grosz and the eclectic poet and art critic Theodor Däubler with reference to their mutual interest in Italian modern art, from Futurism to Metafisica.1 Through the prism of their interaction, it is possible to understand the “double” fortune of Metafisica in Germany in the year 1920 from a political perspective. As is well known, the years 1919 to 1920 were extremely critical for Germany, from the Spartacus uprising to the Kapp Putsch, as well as for Italy, where the Biennio Rosso (Red Biennium) was taking place; during this period the cultural exchanges between the countries appear to have been inextricably linked to their political contexts. Within this historical framework, Grosz approached, in 1920, a style that can be traced back to the imaginations of Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà, an appropriation that had political meaning (figure 1); at the same time, Däubler helped Mario Broglio organize the Valori Plastici exhibition that took place in Berlin in April 1921: “I succeeded in conducting the first Italian exhibition to Berlin,” he declares in December 1920.2 Instead of analyzing the iconographic references to de Chirico and Carrà present in individual works by Grosz,3 I take up this case study to focus on the intricate network of contacts and collaborations that, mostly through art magazines between 1919 and 1920, facilitated the circulation of images by de Chirico and Carrà as part of a shared international visual culture open to multiple interpretations. These activities shed light not only on the effective extent of the Metafisica school in reconfiguring new visual possibilities, but also on political engagement with reference to this “school” in Berlin in 1920.

Theodor Däubler and George Grosz: “Futurist” Temperaments

In the spring of 1912, like many colleagues of his generation, George Grosz was deeply impressed by the exhibition on Futurism organized at Der Sturm gallery in Berlin. In 1914, with the outbreak of the First World War, Grosz volunteered to join the military; he suffered a nervous breakdown in 1917, after being called back to the front, and returned to Berlin. By this time, Grosz’s knowledge and appreciation of Italian modern art started to be linked to his friendship with the Trieste-born German poet Theodor Däubler. Grosz’s friend since 1916, and author of the Expressionist epic of about 30.000 verses entitled “Das Nordlicht” (Nothernlights, 1910), Däubler was, as Marina Bressan has shown, an important “Mediator Between Florentine Futurism and German Modernism.”4 During his extensive travels between September 1913 and April 1914 – which included time in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Leipzig, and Dresden – Däubler was in touch with the Italian Futuristists and took part in several of their “evenings” in Florence,5 as reported in his book Im Kampf für die moderne Kunst (Joining the Battle for Modern Art, 1918). Through his friendships with Aldo Palazzeschi, Giovanni Papini, Ardengo Soffici, Italo Tavolato, Carlo Stuparich, and Augusto Hermet, he published an initial piece of art criticism, on Pablo Picasso, in the magazine Lacerba.6

At the start of the war, Däubler moved to Dresden, and then, in 1916, to Berlin, where his sister Edith Schamberg worked, since 1913, as secretary for Herwarth Walden Gallery Der Sturm. In Germany, alongside his poetic production, he worked as a journalist and an art consultant for private collectors including Ida Bienert and Sally Falk. From September 1916 to October 1918, he was the Kunstreferent (art correspondent) of the magazine Berliner Börsen-Courier, where he published reviews of exhibitions organized by J. B. Neumann, Paul Cassirer, Fritz Gurlitt, and Der Sturm. Between 1916 and 1920, Däubler’s articles on art also appeared in many German art magazines, among them Die Aktion, Zeit-Echo, Die neue Rundschau, Die weißen Blätter, Neue Jugend, Das Kunstblatt, Das junge Deutschland, Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung, Die schöne Rarität, Das Hohe Ufer, Cicerone, Feuer, and Die deutsche Kunst und Dekoration.7 As a poet, Däubler was a master of eclecticism: inspired by classic Greek mythology and by popular German epic, his language is hyperbolic, full of assonances and alliterations and sometimes borders on the grotesque. The poems are often obscure but sustained by a dense visuality: the way image and word interact is synergistic and he maintains the same attitude in his art writings. The art historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub wrote in March 1917 in a review of his book Der neue Standpunkt (The New Point of View, 1916):

Däubler needs the visual arts: their history and even more their next present, which he recognizes as the necessary correlate of his own will. It is part of his creative idiosyncrasy as a poet, he productively evaluates art impressions in a completely new way. […] Däubler’s vision of art is not analytical, formal, psychological; it is not incorporated into any aesthetic category; it is an attempt to translate the visual experience directly into language to test the violent reflection of his poetic receptivity in a vivid impression.8

His idea of art linked tradition to modernity: for his article “Simultanität” (Simultaneity, 1916), Däubler characterized modernity as a simultaneity of styles that made possible the coexistence of Futurism and Expressionism with a surviving idea of classicism.9 This is a constant in his art writings and it allowed him to read Futurism as having evolved from Impressionism and, later, to promote Metaphysics because of its relation with tradition.10 In Germany, he devoted several articles to the Italian context, and in February 1916 edited a special issue of the magazine Die Aktion devoted to Italian modern literature and art: only a few images were included; while none were related to Futurism, it was a rich Italian anthology featuring poems by Aldo Palazzeschi, Giovanni Pascoli, Luciano Folgore, Marinetti, Corrado Govoni, and Paolo Buzzi; an important article on Otto Weininger by Italo Tavolato, entitled “Weininger’s soul” (Die Seele Weininger); and an image by Ardengo Soffici.11 Däubler’s collaboration with Franz Pfemfert magazine should not be understood as a leftist political stance because the writer always avoided political engagements. In this sense, his primary issue was stylistic rather than ideological, and this is true also with regard to the art of George Grosz.

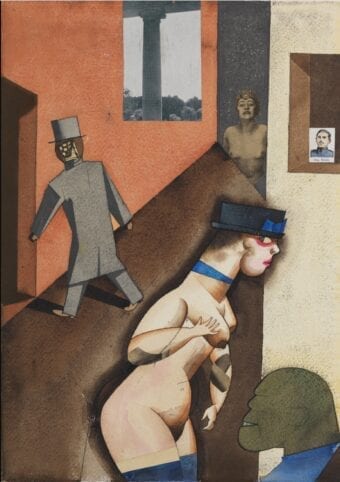

Having first met Grosz in Berlin in 1916 at the Café des Westens in Kurfürstendamm, Däubler avidly followed and promoted his work. Alongside his artistic production, Grosz was writing poetry in these years, which Däubler appreciated as a writer fascinated by the mutual exchange between literature and art. The context of their early acquaintance sheds light on how the two started their collaboration with the Munich gallerist Hans Goltz, a key figure by 1919 in the promotion of Italian modern art in Germany.12 In 1916, Grosz13 and Däubler were both contributing to the magazine Neue Jugend, which involved a group of Berlin-based poets, writers, and artists, many of whom would later take part in Dada and the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity).14 Leftist, antinationalist, and antimilitarist, in 1916 Neue Jugend was promoting Expressionism. Edited by Wieland Herzfelde, Neue Jugend published poems by Däubler, Grosz, and Herzfelde as well as Else Lasker-Schüler, Mynona, and Johannes R. Becher, and involved artists like Grosz, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, and Carlo Mense (figure 2). A letter from Raoul Hausmann to Hannah Höch attests that the magazine was in touch with him and Richard Huelsenbeck,15 which explains the publication of an early review of Zurich Dadaism in its September 1916 issue. Moreover, lectures called “Autorenabend der ‘Neuen Jugend’” (Neue Jugend’s Authors Night)16 took place in cities including Mannheim, Dresden, Munich, and Berlin.17 Hans Goltz was interested in the group and hosted six of their “soirées” in Autumn 1916 and a seventh in March 1917, with poetry readings by Däubler, Grosz, Lasker-Schüler, and Becher.18 Even if Goltz’s interest was mainly literary, thanks to these activities, a first group of artists based in Berlin – Grosz, Davringhausen, and Mense – had direct contact with Goltz’s Galerie Neue Kunst, establishing a Berlin–Munich axis.19

The year 1916 was particularly intense for Däubler’s art writing. That year, while publishing his poems in Neue Jugend and editing the abovementioned issue of the magazine Die Aktion, Däubler wrote an article on the Italian Futurists20 and contributed to the Swiss magazine Die weißen Blätter an article on Henri Rousseau21 and another on Grosz, wherein he described the artist as “the Futurist temperament of Berlin.”22 Däubler linked Futurism to a special “temperament” that he recognized not only in Grosz but also in Paul Klee.23 As Grosz later recalled, Däubler’s article gave him a sudden popularity and, over the next years, Däubler put Grosz in touch with many influential people, among them the collectors Ida Bienert, in Dresden; Sally Falk, in Mannheim; and Paul E. Küppers, from the Kestner-Gesellschaft, Hannover. In February 1917, Grosz took part in the group exhibition Moderne Graphik at Goltz’s gallery, and in 1918 signed a two-year contract with Goltz which was renewed in 1920.24

Moreover, the whole November 1918 issue of Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung, edited in Dresden by the publisher Emil Richter, was focused to Däubler, with many reproductions of works by Grosz and two of the painter’s social satirical poems: “Gesang an die Welt” (Singing to the World) and “Kaffeehaus” (Coffeehouse). The article Däubler dedicated to Grosz in this issue underlined the particular cynical “exactitude” of his style as like that of a “machine”: “no sun […] but nothing remains in the shadow […]. [Grosz] puts before us the contents of these human boxes [houses].”25 Similarly, the poem “Kaffeehaus” describes the interior of a café marked by masks, gas lamps, and rigid geometries; it ends with reference to a broken machine and neurasthenia: “Waiter! A glass of seltzer please / I am a machine whose pressure gauge has gone to pieces! / And all the cylinders run in circles / See: we are all neurasthenics!”26 Grosz’s poems, like his drawings, link to the experience of the metropolis as a shock; they provide a cynical vision of reality, with similarities drawn from the world of the machine and populated by phantom-like personages rendered in a childish and satirical graphic style. The issue reflects Däubler’s ideas on a mutual relationship between the visual arts and poetry, already evident, by 1918, in the editorial project he had with the artist Paul Klee.27

By this time, Däubler was very critic against Dadaism and was instead oriented toward a “new classicism.” As is known, thanks to his previous friendships with the Italian Futurists, he was early on aware of the new direction taken by the group surrounding Valori Plastici: he shared their renewed relation between tradition and modernity and saw many affinities with his own poetics, as can be understood in reading his book of poems Hymne an Italien (Hymn to Italy, 1916). Beginning in June 1919, he wrote several articles for Valori Plastici that served as a sort of history of modern art, from Paul Cézanne to Aristide Maillol, entitled “Nostro Retaggio” (Our Heritage), and, in parallel, promoted the Italian group in German magazines.28 In 1919, Däubler writes a new article on Grosz where, intentionally, he does not mention Grosz’s active participation in Berlin Dada but compares again his art to Futurism: “Futurism is crystallized. […] There is order in George Grosz.”29 In 1920, while representing opposite viewpoints, the names of Grosz and Klee appeared together in Goltz’s magazine Der Ararat because of their shared graphic “Infantilism,” and also in the Italian magazine Valori Plastici.30 Their “Infantilism” was considered a positive approach to a new “figuration” opposed to Dadaism, which was understood to be a mad and destructive art.31

Dadaist Discrepancy

The critical position taken by the Valori Plastici group against Dadaism is unsurprising considering that in Italy, by 1920, Dadaism didn’t have a strong impact in the art world and was often criticized.32 In Munich, this same position was more controversial. As Maria Elena Versari underlines in her essay “‘Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor’: Expectations, Misunderstandings, and Appropriations of Pittura Metafisica Among the 1920s European Avant-Garde,”33 in an article for Der Ararat entitled “Dadaismus oder Klassizismus?” (Dadaism or Classicism?), Leopold Zahn criticized Dadaism and underlined how crucially important it was not to follow it: he pointed out that the real “Revolutionary Dadaists” were Hausmann, Huelsenbeck, and Jefim Golyscheff, then cited Klee and Grosz to demonstrate their differences from Dadaism.34

As is known, the impact of a new ‘Classicism’ and of Metafisica in Germany occurred when the so-called ‘end of Expressionism’ reached its peak.35 In April 1920, the influent leftist art critic Wilhelm Hausenstein – echoing the arguments already expressed by Hartlaub, Edschmid, Worringer since 1918 – declared himself disappointed in the outcome of the Revolution and, as Joan Weinstein pointed out, “fled the world of politics for that of art, announcing the end to their political hopes with the end of Expressionism. From another quarter, though, came a more trenchant critique of expressionism, one waged still in the name of revolutionary politics. This was the assault of Berlin Dada. […] One of their prime targets soon became expressionists, whose growing success and spiritualization – they saw as part of an escapist bourgeois culture responsible for the war and its carnage.”36 By 1920, in Germany ‘Dadaismus oder Klassizismus‘ were considered the two possible solutions to overcome Expressionism.

In retrospect, what made Zahn’s article particularly controversial was its publication during Grosz’s first solo show at Goltz’s gallery, in April 1920 – for Zahn knew of Grosz’s involvement in Dada. Zahn’s article against Dadaism should be understood as a political stance. In fact, it should be pointed out that, by December 1919, as a consequence of the Bavarian Soviet Republic (April–May 1919), Hans Goltz, as owner of the magazine, was affirming that “Der Ararat, which until now has been published as a political flyer, from January 1920 will only support the new art [because] descending into the arena of daily politics one is seized by passions that obscure the view.”37 In the following months, the political situation in Germany was still very difficult: the Kapp Putsch, a failed nationalist and monarchist coup in Berlin lead by Wolfgang Kapp on March 13, 1920, was followed by widespread strikes in several German cities. By this time, Berlin Dada’s involvement with extreme leftist politics (Kulturbolschewismus) was viewed with suspicion; many Dadaists were considered Bolsheviks because they were members of the communist party (KPD). Among them, Grosz, who had joined the KDP in December 1918, represented, with John Heartfield (Helmut Herzfelde) and Wieland Herzfelde, the “left wing” of the movement.38 In their work toward a proletariat art, they battled against the bourgeois art business and against Expressionism. In March 1920, a strike on the Postplatz in Dresden between federal troops and demonstrating workers – in which fifty-nine people died – ended with the damage of Rubens’ work Bathsheba in the Zwinger Museum. Few days later, Oskar Kokoschka published his protest in forty German magazines, defending the masterpiece against any political struggle. In April 1920, coinciding with Zahn’s article against Dadaism, Grosz and Heartfield published, in the magazine Der Gegner, their article “Der Kunstlump” (The Art Scab), decrying the elitist views of Kokoschka, whom they called the “republican professor at the art academy.” They attacked the capitalist art system in favor of the proletariat:39

Today, it is more important that a red soldier cleans his rifle than the entire metaphysical work of all painters. […] With Joy we welcome the news that the bullets are whistling through the galleries and palaces, into the masterpieces of the Rubens instead of into the houses of poor in the working-class neighborhood! […] Every indifference is counter-revolutionary!40

The article underlined the importance of subverting the bourgeois and capitalist art system from within the institutions themselves: in this sense, the Dadaist appropriation of the “Metafisica” style can be interpreted, too, as an attack against this system.

Däubler, in contrast, kept himself distant from any political involvement, which meant distancing himself from Dada. On January 22, 1918, after participating by chance with Grosz in the first Dada soirée, organized in Berlin at the J. B. Neumann Gallery in Kürfurstendamm, he immediately criticized the night.41 In May 1918, Grosz wrote to Otto Schmalhausen a letter revealing that Däubler did not get along with Huelsenbeck and Franz Jung,42 for they attacked Expressionism directly and considered Däubler a “gigantosaurus of Expressionist poetry.”43 In 1918, Däubler published the statement: “Art doesn’t have anything to do with politics.”44 On March 23, 1919, Herzfelde showed to Harry Graf Kessler his disinterest in publishing any poem by Däubler in the magazines edited by the Dadaist publisher Malik Verlag.45 A few days later, on March 27, Graf Kessler wrote in his diary: “Däubler asked me how he got a pass to Switzerland and mentioned that he would be Italian after the peace will be signed. […] He is a small person. The somewhat contemptuous judgement he receives from Herzfeldes, Becher, Grosz is justified.”46

Within a few months, Däubler distanced himself from the Berlin circles and decided to move away from the city. By 1920, he was being hosted by Sally Falk for three months in Geneva. A letter that Falk wrote to Grosz – undated but probably written in this period – suggests that the artist did not defend Däubler from the Dadaist attacks:

The circle of “Dadaism” does not want to support him [Daübler] […]. What your friends are doing against Däubler – I recall the call for the Nobel Prize – is tasteless. On your behalf – [the fact] that you did not prevent such things – you owe Däubler very much. However, the word “gratitude” seems to belong to the words of “useless emotional showering” […]. Däubler as a poet is a thousand times better than Jung, Huelsenbeck etc. / your Falk.47

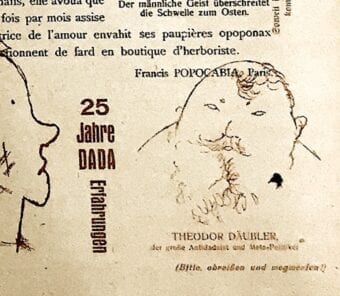

In April 1920, the separation between Däubler and Grosz because of their differing views on Dadaism and on the relation between politics and art became evident in Grosz’s caricature Theodor Däubler, der Großer Antidadaist und Metapolitiker, Bitte abreißen und wegwerfen (Theodor Däubler, the great anti-Dadaist and meta-politician, please tear off and throw away; figure 3), which was published in the third issue of the magazine Der DADA, edited by Hausmann, Grosz, and Heartfield.48 The title of “Metapolitician” refers to the distance taken by Däubler from any politic involvement.

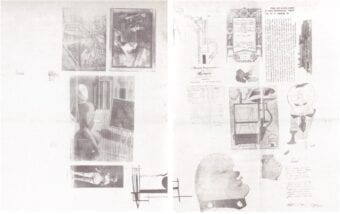

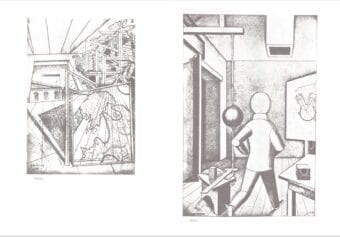

By this time, from different perspectives, Berlin Dadaists and Däubler were interested in Italian modern art and, in particular, in de Chirico: the Italian artist was mentioned in the issue of Der DADA as member of the “International Dada Company.”49 As the art historian Dennis Crockett has pointed out, because of his earlier involvement in Zurich Dada, “according to Richard Huelsenbeck and Tristan Tzara, [de Chirico] was representative of Italian Dada,”50 and this explains why a draft for the Dadaist magazine Dadaco (1919–20; figures 4a–4b) contains several illustrations by Dadaists – Grosz, Schwitters, Hausmann, Francis Picabia, and Johannes Baader – next to two works by de Chirico (Il profeta [The Prophet], 1915; Le printemps géographique [Geographic Spring], 1916).

The art of de Chirico was having a deep impact in Berlin: writing for Das Kunstblatt in January 1920, Carl Einstein – who edited with Grosz and Heartfield the magazine Der blutige Ernst (Bloody Serious) and also tried to include images of de Chirico and Carrà in the December 1919 issue of the magazine, but with no success51 – underlined the fact that “for six weeks now, futurists in the Berlin suburbs have been looking at Valori Plastici. De Chirico, who was managed in Paris in 1911, landed 20 [in 1920] in Berlin and in a short time we will be delighted with perspective.”52

Between Dadaism, Tatlinism and Metafisica: Die Neue Gegenständlichkeit

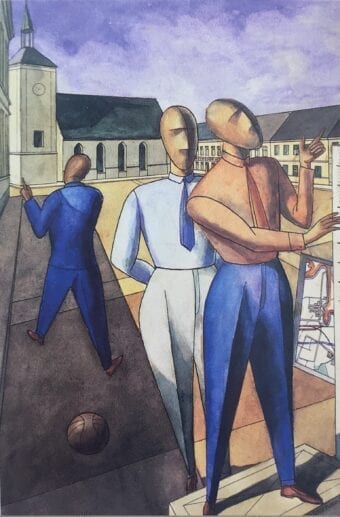

By this time George Grosz and Richard Hausmann were both referring to Metafisica in their works. In fact, by 1920, Grosz, who was called by his artist friends “Dada Marshall and Propagandada” because he was politically engaged and acted as a Prussian general to mock militarism, started working more intensively with Hausmann, the Berlin “Dadasoph,” or theorist of Dada.53 Dada strategy consisted in mocking art movements and artists, from Henri Rousseau to Picasso, nevertheless towards Valori Plastici the attitude was more complex: as demonstrated by Versari in her aforementioned essay, by this time the art of Valori Plastici was related to what was known about Tatlinism thanks to an early article by Konstantin Umansky on the new Russian art, entitled “Der Tatlinismus oder die Maschinenkunst” (Tatlinism or Machine Art) and published in Der Ararat in January 1920.54 Of course, by 1920 any reference to Tatlinism had deep political meaning – directly related to Kulturbolschewismus and collectivism. A text written by Hausmann before February 1920 in typically Dadaist satirical language, “Rückkehr zur Gegenständlichkeit in der Kunst” (Return to Representational Art), contains many references to the Italian art and the Russian art.55 Hausmann wished for Germany to overpass Expressionism with a third kind of Gegenständlichkeit, able to include both the new centrality of machines – so evident in Russian post-revolutionary art – and the clarity of perspective characteristic of Italian modern art, but free from spiritual meaning, as underlined by his pointing out the “uselessness of geometric volumes in relation to the sky.”56 In this sense, Hausmann was already skeptical against the concept of Metafisica because of its relation “to the sky” and not to reality: using Metafisica to depict dehumanized modern society was a denial of its transcendent meaning in favor of the concreteness of reality. Hausmann and Grosz made the Metaphysical meaning attributed to bourgeois art explode from within. Hausmann ended his “Rückkehr zur Gegenständlichkeit in der Kunst” with the statement that this new direction toward reality “swings from a Romanic to a Moscow pole.”57 His “Italian-Russian” reference is evident in the watercolor Die Ingenieure (The Engineers, 1920; figure 5), with its symbol of the “New Engineer” working in team toward the development of a future society. The work was inspired by photographs of Tatlin making his Monument of the Third International (also called Tatlin’s Tower, 1919–20; figure 6) as well as by de Chirico’s Il cattivo genio di un re (The Evil Genius of a King, 1914–15). A comparison of the watercolor with Tatlin’s photographs reveals many similarities in the cut of the image and the gesture of the man on the right, who holds a long board while looking up. The idea of the “New Man” able to construct the future society came from the new communist society in Russia, and its symbol was Tatlin’s Tower. In the image, the clarity of perspective is taken as instrumental, for the objectivity of expression and the geometric volumes are not “useless in relation to the sky,” but fasten to the materiality in the making of a “New Society.”

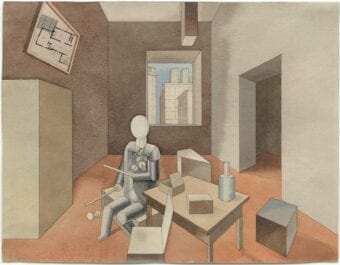

In this intricate context, Grosz also realized a group of watercolors related to Metafisica.58 Grosz’s strategy was to accompany the proletariat in a new awareness of its role in society with the foundation of a new model of man – the New Man – in the heavily industrialized suburbs of Berlin. Grosz could use the Metaphysical model as an anti-Expressionist solution to move toward a new sense of proto-Constructivist materialism: a political instrument to subvert (intentionally) the idealistic Metafisica in favor of a mechanized approach to art.59 In this sense, his primary issue was ideological rather than stylistic.

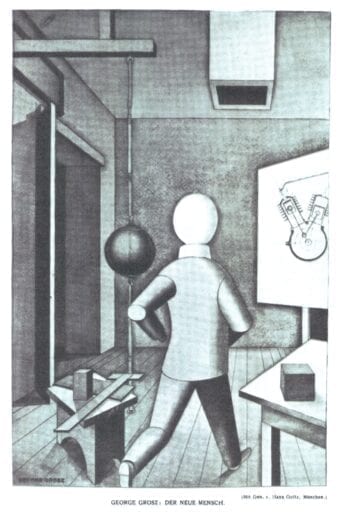

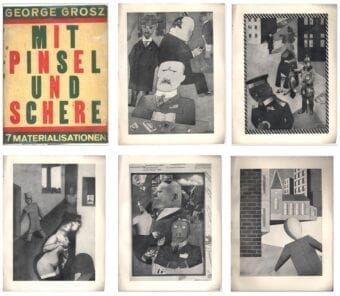

As it has been underlined, most of the articles on Grosz published around 1919 and 1920 did not mention Dadaism or Grosz’s political engagement in KPD, nevertheless the artist proceeded with an institutionalized subversion thanks to this group of works referring to the style of Metafisica: these watercolors were reproduced in art magazines such as Der Ararat or Das Kunstblatt, and they were on view at institutional art fairs and exhibitions like the Neue Kunst Gallery in Munich or at the Exposition Internationale d’Art Moderne in Geneva – but, of course, not included in the First International Dada Fair in Berlin (June 30 — August 25, 1920). Significantly, what seemed a more traditional approach to art was justified by a call for materiality in painting made clear in the unpublished manifesto “Die Gesetze der Malerei” (The Laws of Painting), which Grosz and Hausmann signed in September 1920 together with Heartfield and Rudolph Schlichter.60 This text, as Roland März underlined, confirms the fact that these artists were looking to a future society where the artist would have a new role as constructor, and the only metaphysics that would exist would be of a materiality by which painting must be collective. “Painting is a language that must increase the visual conceptions of the masses for clarity.”61 As can be observed in Grosz’s watercolor Der neue Mensch (The New Man, 1920; figure 7),62 the watercolor technique facilitated a clear style of depiction: simple backgrounds of a stage-like space with mechanical drawings on the walls and mechanized human beings holding various scientific instruments. In the manifesto, the artists mentioned also the few colors they might use in these works “to give the solidity”; they go on to say that “they are not used to represent intoxication. All shadows are brown, the brightnesses gray-blue.” For similar reasons, they praised photography and the use of photomontage for reaching a neutral and universal vision and “the disintegration of aura under the conditions of mass-reproduction and the mass media.”63 In a work by Grosz from 1920, Tatlinesque Diagramm (figure 8), both photomontage and watercolor are instrumental to abandoning individuality in favor of collectivity and universality. These techniques are equally valid, because they offer a materialization of reality “with pencil and scissors,” as shown in Grosz’s book Mit Pinsel und Schere. 7 Materialisationen (With pencil and scissors. 7 Materializations, 1922; figure 9).

In examining these works inspired by Metaphysical painting, it should not be overlooked that they occupied the artists for only a short time and that the aforementioned manifesto “Die Gesetze der Malerei” was never published probably because, with information more available by the end of 1920, opinions on de Chirico had begun to change. By October 1920, after traveling to Italy, Hannah Höch received as a gift from Raoul Hausmann the richly illustrated monograph of de Chirico’s work entitled 12 Opere di Giorgio de Chirico, edited by the Valori Plastici publishing house.64 In November 1920, Grosz wrote an article specifically intended to explain his style, “Zu meinen neuen Bildern” (On My New Paintings), which he illustrated with “metaphysical” watercolors realized in 1920 for Goltz’s gallery: “I try to give an absolute realistic image of the world.”65 The artist admitted to being very close to the art of Carrà, while underlining how totally different their artistic purposes were – because Carrà’s problems were Metaphysical and bourgeois. In contrast, the “New Man” depicted by Grosz in his watercolors was not elitist but rather a collective human being. Plasticity, Stability, Structure, Equilibrium, Control, Objectivity, and Clarity were his new principles, and they drove him away from “the temple of the arts,”66 toward real factories as the new places where modern painting could be developed. As Dennis Crockett has pointed out, this new Gegenständlichkeit as political stance to overcome Expressionism was renewed in 1921 in the “Offener Brief an die Novembergruppe” (Open letter to the November Group) signed by Grosz and Hausmann among the others and published in Der Gegner. They wished “to overcome the trade in aesthetic formulas through a new Gegenständlichkeit, which will be born out of the disgust with the exploitative bourgeois society […] in order to discard individuality for the sake of a new human type.”67

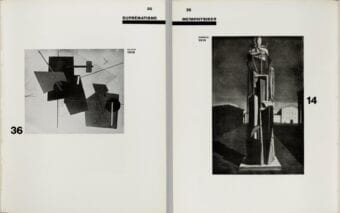

In the same months, Hausmann’s philosophical interests drove him to focus less on politics and more on “perception and thought as mechanical,”68 and to approach art as a form of scientific experimentation with perception. By 1921, he would take a new direction with his interest in Optophonie69 and science in general: he became no longer interested in representing the New Man, and instead intended to transform human perception in the modern world through technological advancements. By December 1921, Hausmann’s pseudo-scientific approach to art wasn’t convincing Grosz anymore,70 and any analogizing between their styles ends here.71 Nevertheless, other artists oriented towards collective art and Russian Constructivism inherited this constructive interpretation of the Metaphysical style, as is evident, for example, in the Buch Neuer Künstler (Book of the New Artists, 1922; figure 10), edited in Berlin by Lajos Kassák and Làszlò Moholy-Nagy, who would become a teacher at the Bauhaus in 1923. In Kassák and Moholy-Nagy’s book, to affirm their analogies, de Chirico’s Le printemps géographique (Geographic Spring, 1916) is put in parallel with Grosz’s Der neuer Mann (The New Man, 1920).72

The gallery contract between Goltz and Grosz was not renewed in 1922.73 As Dieter G. Gessner has pointed out, the reason was political: “Goltz was a wool-dyed conservative who disapproved of Grosz’s ties to the Herzfelde brothers. He broke up in 1922. With the words ‘It sucks that a person sinks into the political stump of the party with his talent.’”74 In the same year, his answers to an opinion survey entitled “Ein neuer Naturalismus? Eine Rundfrage der Kunstblatts” (A new Naturalismus? A Kunstblatt poll), published in the magazine Das Kunstblatt, underline his political decision to leaving behind this style position: “[T]he so-called Gegenständlichkeit is worthless to us today. Going back to classic French painting: Poussin, Ingres, and Corot, is a bad Biedermeier fashion. It seems that the political reaction now follows the intellectual one.”75 At the invitation of the KPD, Grosz moved in 1922 for six months to Russia with the Danish writer Martin Andersen-Nexo.

Other artists shared Grosz’s early fascination with Futurism and his later stand against Metafisica: the Constructivist artist El Lissitzky and the Dadaist Hans Arp, editing their book on modern art, Die Kunstismen, in 1925, underlined the formal analogies between constructive forms and De Chirico’s geometries (figure 11), but then they described the Metafisica as a “Futurist betrayal”:

To represent the immaterial by the material is the problem of the metaphysicians. As futurists they would put fire to the museums, as metaphysicians they are happy to use museums as asylums for the old age. This is the punishment for having wished to measure eternity with three cow tails.76

Inside a museum, in 1921, the art of Valori Plastici was finally presented to a wider German public.

Theodor Däubler and the Valori Plastici Exhibition in Berlin

By May 1920, Däubler published the article “Neueste Kunst in Italien” (Newest Art in Italy) on Valori Plastici in two different German magazines, Jahrbuch der jungen Kunst and Der Cicerone.77 Däubler ended this article with a wish for a future exhibition in Germany of these artists: by May 1920, he was already working on this exhibition project. It would take place in Berlin, opening at the Kronprinzenpalais in April 1921.78 In a letter to Hermann Schmitt dated December 2, 1920, Däubler clarified his central role: “I succeeded in conducting the first Italian exhibition to Berlin. I am very happy about this success; and it means the presentation of the Romans to the Germans.”79 By this time, his poetic work was aligned with the sense of tradition and new mythical classicism defended by the Valori Plastici group: already in 1919, Däubler’s Hymne an Italien was reviewed in Das Kunstblatt as “a metaphysics of language that leads from the phenomena to primal backgrounds and secrets.”80 On December 25, 1920, Däubler penned a postcard to Justi from Geneva, proclaiming: “Mr. Broglio wrote me!” He also asked Justi about his duties for the Italian exhibition,81 and took the opportunity to briefly comment upon artworks currently on view at the Exposition Internationale d’Art Moderne in Geneva. Däubler gave a lecture at the exhibition’s opening and read part of his writings concerning Italy, probably taken from his poem “Hymne an Italien.”82

The Valori Plastici exhibition in Berlin was deeply connected to a wider strategy of cultural politics, both institutional and private. After the First World War’s end, Germany was isolated from the rest of Europe, hit by a galloping inflation, and under stress due to the high war reparations asked by France and Britain. Berlin was still the intersectional center of an international artistic crossroads, and the starting point for many editorial and exhibition projects. Ludwig Justi, director of the German National Museums, institutionally supported a cultural politics of “exchange exhibitions” (Wechsel/Ausstellungen). After a show in December 1920 on new art tendencies coming out of Holland, Italy was the second country to be considered for this program at the National Gallery. Both of these exhibitions took place during the preparation of the “London Schedule of Payments,” which established, in 1921, the payment of reparations by the German government up to the sum of 132 billion gold marks. This explains why Mario Girardon, a financial supporter of the Valori Plastici group, wrote to Justi that the exhibition in Berlin should demonstrate to Britain and France the “unchanged friendship” between Italy and Germany.83 Justi in 1919 opened the Kronprinzenpalais, which, as an early example of a contemporary art museum, gave preeminence to German Expressionist works. The large inclusion of modern art so distant from Impressionism and “apparently” leftist was criticized by many conservatives. Justi welcomed the Italian exhibition project in part because this new tendency was clearly distant from Expressionism and Dadaism. Meanwhile, the conservative critic Karl Scheffler attacked Justi’s politics in a nationalist tone in a series of articles and a pamphlet, Berliner Museumskrieg (Berlin Museum War, 1921), that called for Justi’s removal from his position. The Italian exhibition, so deeply linked to “traditional values,” can be read as a compromise against these attacks.84

A few weeks prior to the Berlin opening, in Milan Carlo Carrà announced the exhibition in the Italian magazine I.I.I. Le Industrie Italiane Illustrate (Italian Illustrated Industries), and reported the antagonism against the exhibition on the part of Bolshevik artists: “Since there is no rose without thorns, there are also some hostilities that come from the group of pan-Germanist and Bolshevik artists – almost all from Russia and Polland […]. Do they really believe they give us great displeasure with their opposition?”85

Bibliography

12 Opere di Giorgio de Chirico precedute da giudizi critici di Soffici, Apollinaire, Louis Vauxcelles, Raynal, Jacques-Emile Blanche, Roger Marx Papini, Carrà, Etienne Charles ([Rome]: Valori Plastici, [1919]).

Beals, Kurt. “Text and the City: George Grosz, Neue Jugend, and the Political Power of Popular Media.” Dada/Surrealism, no. 19 (2013), n.p, https://doi.org/10.17077/0084-9537.1280.

Benson, Timothy O. Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1987.

Berlinische Galerie, ed., Hanna Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, 1919–1920. Archiv-Edition, vol. 1, no. 2, Berlin: Berlinische Galerie and Argon, 1989.

Biro, Matthew. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Bressan, Marina. “L’esperienza futurista di Theodor Däubler a Firenze.” Studia austriaca 22 (2014): 125–37.

Bressan, Marina. “Theodor Däubler: A Mediator Between Florentine Futurism and German Modernism.” International Yearbook of Futurism Studies 4, (2014): 450–76.

Crispolti, Enrico. “Dada a Roma. Contributo alla partecipazione italiana al Dadaismo.” Palatino 12, no. 1 (January–March 1968): 51–56; no. 2 (April–June 1968): 187–96; no. 3 (July–September 1968): 294–99.

Crockett, Dennis. German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder 1918–1924. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

Dada, no. 2 (July 1917).

Däubler, Theodor. “Georg Groß.” Die weißen Blätter 3, no. 4 (1916): 167–70.

Däubler, Theodor. “George Grosz.” Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung 1 (November 1918): 153.

Däubler, Theodor. “Futuristen.” Die neue Rundschau 27 (1916): 414–20.

Däubler, Theodor. Im Kampf für die moderne Kunst. Berlin: Erich Reiss Verlag, 1918.

Däubler, Theodor. “Henri Rousseau.” Die weißen Blätter 3, no. 1 (1916): 239–43.

Däubler, Theodor. Letter to Hermann Schmitt, December 2, 1920. Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Theodor-Däubler-Archiv.

Däubler, Theodor. Letter to Ludwig Justi, December 25, 1920. Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin, Nachlass Ludwig Justi.

Däubler, Theodor. “Moderne Italiener.” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 1 (1921): 49–53.

Däubler, Theodor. “Neueste Kunst in Italien.” Der Cicerone 12, no. 9 (May 1920): 349–55.

Däubler, Theodor. “Simultanität.” Die weißen Blätter 3, no. 1 (1916):108–21.

Däubler, Theodor. “Georg Grosz.” Das junge Deutschland 2 (1919): 175–177.

Däubler, Theodor. “Nostro retaggio.” Valori Plastici 1–3 (1919).

Däubler, Theodor, Ferdinand Hardekopf, and Titus Tautz. “Distanzierung vom ‘Club Dada’ und Verwahrung gegen des Mißbrauch ihrer Namen.” Berliner Börsen-Courier (February 2, 1918): 5.

Die Aktion 4, nos. 7–8 (February 19, 1916).

Doherty, Brigid. “The Work of Art and the Problem of Politics in Berlin Dada,” October 105 (Summer 2003): 73–92.

“Ein neues Rinascimento der italienischen Kunst.” Der Ararat, no.1 (January 1920): 10.

Einstein, Carl. “Giorgio de Chirico.” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration 31, no. 4 (1928): 259–66.

Einstein, Carl. “Giorgio de Chirico.” In Giorgio de Chirico. Berlin: Galerie A. Flechtheim, 1930. Exhibition catalogue.

Einstein, Carl. “Rudolf Schlichter.” Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 4, April 1920: 105–08.

Füllner, Karin. Dada Berlin in Zeitungen: Gedächtnisfeiern und Skandale. Siegen: Universität-Gesamthochschule-Siegen/MuK, 1986.

Gessner, Dieter K. “Avantgarde und Kunstmarkt. Der Zeichner George Grosz in der Weimarer Republik.” Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 55, 2015: 343–72.

Girardon, Mario. Letter to Ludwig Justi (March 8, 1921). Staatliche Museen Archiv Berlin, 1163/20.

Goltz, Hans. “Der ‘neue’ Ararat.” Der Ararat, no. 1 (January 1920): 1.

Grosz, George. Briefe 1913–1959. Edited by Herbert Knust. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1979.

Grosz, George. “Ein neuer Naturalismus? Eine Rundfrage des Kunstblatts.” Das Kunstblatt 9 (September 1922): 382–83.

Grosz, George. “Kaffeehaus.” Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung 1 (November 1918): 155.

Grosz, George. “Zu meinen neuen Bildern.” Das Kunstblatt 5 (January 1921): 11–14, 16.

Grosz George, Hausmann, Raoul et al. “Offener Brief an die Novembergruppe,” Der Gegner 2, 1920/21, Nos. 8–9: 297–301.

Hartlaub, Gustav F. “Däubler Standpunkt.” Das Kunstblatt 1, no. 3 (March 1917): 91–92.

Hartlaub, Gustav F. “Der Genius im Kinde.” Kunst und Jugend 1, no. 3 (1921): 41–44.

Hausmann, Raoul. “Rückkehr zur Gegenständlichkeit in der Kunst.” In Dada Almanach, edited by Richard Huelsenbeck, 147–51. Berlin: Erich Reiss Verlag, 1920.

Hausmann, Raoul, George Grosz, John Heartfield, and Rudolf Schlichter. “Die Gesetze der Malerei.” In Berlinische Galerie, ed., Hanna Höch: 696–98.

Haxthausen, Charles W. “Bloody Serious: Two Texts by Carl Einstein.” October 105 (Summer, 2003): 105–18.

Heartfield, John, and George Grosz. “Der Kunstlump.” Der Gegner 1, nos. 10–12 (April 1920): 1.

Huelsenbeck, Richard. En avant Dada. L’histoire du dadaïsme. Paris: Les presses du reel, 2005.

Interlandi, Telesio. “Dadà.” Noi e il mondo 10 (October 1920): 748–52.

Kersten, Wolfgang F. “Von der Kosmogonie zum Ikonoklasmus.” Zwitscher-Maschine. Journal on Paul Klee / Zeitschrift für internationale Klee – Studien, no. 6 (2018): 4–29.

Kessler, J. Harry Graf. “Tagebucheintragung.” In John Heartfield, Der Schnitt antlang der Zeit. Dresden: VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1981.

Klee, Paul. “Tagebücher. 1898–1918.” Cologne: DuMont Schauberg 1957: 31.

Justi, Ludwig. Letter to Mario Broglio, February 12, 1921. Staatliche Museen Archiv Berlin, 1163/20.

Laur, Elisabeth. “Theodor Däubler,” in “Porträits von Künstler seiner Zeit.” In Ernst Barlach, Theodor Däubler. Die Welt versöhnt und übertönt der Geist, edited by Volker Probst and Helga Thieme, 19–24. Güstrow: Ernst Barlach Stiftung, 2001.

Lauverjat, Ghislain. “Vision optophonique (1919–1971). Raoul Hausmann et les sources scientifiques de l’optophonie.” In Raoul Hausmann et les avant-gardes, edited by Timothy O. Benson, Hanne Bergius, and Ina Blom, 169–94. Paris: Les Presses du réel, 2015.

Lepik, Andres. “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico Italia-Germania.” In Valori Plastici, edited by P. Fossati, P. Rosazza Ferraris, and L. Velani, 154–70. Milan: Skira, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

Lochmaier, Katrin. “Die Galerie ‘Neue Kunst – Hans Goltz’ München 1912 – 1927: Aspekte der Vermittlung zeitgenössischer Kunst im ersten Drittel des 20. Jahrhundert.” PhD diss., Kassel, 1997.

Lhot, Patrick. L’indifférence créatrice de Raoul Hausmann. Aux sources du dadäisme. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaire de Provence, 2013.

März, Roland. “Republikanische Automaten. George Grosz und die Pittura metafisica.” In George Grosz: Berlin-New, edited by Peter Claus, 146–56. Berlin: Neue Nationalgalerie, 1994. Exhibition catalogue.

Maur, Karin V. “Carrà und Deutschland.” In Carrà, edited by Jochen Poetter and Dirk Teuber, 11–21. Baden-Baden: Staatliche Kunsthalle, 1987. Exhibition catalogue.

Messina, Maria Grazia. “L’espressionismo nell’area di Valori Plastici.” In L’expressionnisme. Une construction de l’autre, edited by D. Jarrassé e Maria Grazia Messina, 61–76. Paris: L’Esthétique du divers, 2012.

Neue Jugend, no. 9 (September 1916): 185.

Neue Jugend, nos. 11–12 (February–March 1917): 245.

Paoletti, Valeria. Dada in Italia. Un’invasione mancata. PhD diss., Viterbo, 2009.

Rehnolt, Juliane. Dichterbilder der Moderne. Gerhart Hauptmann, Stefan George und Theodor Däubler im Porträt. Dresden: Thelem, 2017.

Savinio, Alberto. “Bizzarrie Artistiche: Dadaismo.” Popolo d’Italia, July 28, 1919.

Scholz, Dieter. “Faschistische Bilder in der Nationalgalerie? Italienische Gegenwartskunst in Berlin 1921–1933.” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 53 (2011): 131–46.

Schwitters, Kurt. “ Merz,” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1921): 3–9.

Tavolato, Italo. “La Maschera della meccanica.” Valori Plastici, nos. 5–6 (May 1920): 50.

Tavolato, Italo. Georg Grosz. Rome: Valori Plastici, 1924.

Kemp, F., and F. Pfäfflin, eds. Theodor Däubler. Im Kampf um die modern Kunst und andere Schriften. Darmstadt: Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 1998.

Umansky, Konstantin. “Der Tatlinismus oder die Maschinenkunst.” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 12.

“Umschau,” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 2 (1919): 186.

Westheim, Paul. [Untitled]. Das Kunstblatt 3 (October 1919): 319.

Zahn, Leopold. “Dadaismus oder Klassizismus?” Der Ararat, no. 4 (April 1920): 50–52.

Zahn, Leopold. “Ein neues Rinascimento der italienischen Kunst?” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 10.

Zahn, Leopold. “George Grosz-Paul Klee.” Valori Plastici 2, nos. 7–8 (July–August 1920): 88–89.

Zahn, Leopold. “Italien. Die metaphysische Malerei.” Der Ararat 1, no. 4 (January 1920): 8.

Zahn, Leopold. “Über den Infantilismus in der neuen Kunst.” Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 3 (March 1920): 5–7.

How to cite

Carlotta Castellani, “‘Dada Marshall and Propagandada’ George Grosz and ‘Metapolitiker’ Theodor Däubler: Metafisica and Politics in Berlin, 1920,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- The interest in the connection between George Grosz and Metafisica arises as part of a study of affinities between his work and that of Mario Sironi. Scholars have analyzed the group of works realized in 1920 by the Berlin-based artists Grosz and Raoul Hausmann for their style, clearly influenced by the Italian artists Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. See Timothy O. Benson, Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1987), 163–211; and Karin V. Maur, “Carrà und Deutschland,” in Jochen Poetter and Dirk Teuber, Carrà (Milan: Mazzotta, 1987), 11–21; See Roland März, “Republikanische Automaten. George Grosz und die Pittura metafisica,” in Claus, ed., George Grosz, 146–56. All translations, unless otherwise noted, are the author’s.

- Theodor Däubler, letter to Hermann Schmitt, December 2, 1920, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Theodor-Däubler-Archiv.

- See Roland März, “Republikanische Automaten. George Grosz und die Pittura metafisica,” in Peter Claus, ed., George Grosz: Berlin-New (Berlin: Neue Nationalgalerie, 1994): 146–56.

- See Marina Bressan, “Theodor Däubler: A Mediator Between Florentine Futurism and German Modernism,” International Yearbook of Futurism Studies 4 (2014): 450–76.

- Däubler’s first stay in Florence was in 1907.

- Däubler’s first article of art criticism, “Deux Peintres Polonais,” was published in 1904 in L’Europe Artiste. On his relationship with Futurism, see Marina Bressan, “L’esperienza futurista di Theodor Däubler a Firenze,” Studia austriaca 22 (2014): 125–37.

- See F. Kemp and F. Pfäfflin, eds., Theodor Däubler. Im Kampf um die modern Kunst und andere Schriften (Darmstadt: Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 1998), 251–65.

- Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, “Däublers Standpunkt,” Das Kunstblatt 1 (March 1917): 91–92.

- Theodor Däubler, “Simultanität,” Die weißen Blätter 3, no. 1 (1916):108–21.

- Juliane Rehnolt, “Dichterbilder der Moderne. Gerhart Hauptmann, Stefan George und Theodor Däubler im Porträt” (Dresden: Thelem 2017), 170–90.

- Die Aktion 4, nos. 7–8 (February 19, 1916).

- Leopold Zahn, “Italien. Die metaphysische Malerei,” Der Ararat 1, no. 4 (January 1920): 8; and, in the same issue, “Ein neues Rinascimento der italienischen Kunst?”: 10. See also Lepik, “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana?,” 159.

- On Grosz and Neue Jugend, see Kurt Beals, “Text and the City: George Grosz, Neue Jugend, and the Political Power of Popular Media,” Dada/Surrealism, no. 19 (2013), https://doi.org/10.17077/0084-9537.1280.

- The Berlin magazine Die Freie Strasse played a similar role from 1915 to 1918.

- See Raoul Hausmann Sammlung Online, Berlinische Galerie online Sammlung, n. inv. 207213, https://uclab.fh-potsdam.de/hausmann/attributebased.html#207213.

- See Neue Jugend, no. 9 (September 1916): 185.

- See ibid. and Neue Jugend, nos. 11–12 (February–March 1917): 245. In Berlin these lectures took place at the Graphische Kabinett I. B. Neumann, Kürfurstemdamm 232.

- The first was on Mynona (September 8), then: Else Lasker-Schüler (September 26); Alfred Wolfenstein (October 10); Theodor Däubler (October 17); Franz Kafka (November 10); and Däubler, Lasker-Schüler, Joahnnes R. Becher, and George Grosz (November 17). See Katrin Lochmaier, “Die Galerie ‘Neue Kunst – Hans Goltz’ München 1912–1927: Aspekte der Vermittlung zeitgenössischer Kunst im ersten Drittel des 20. Jahrhundert,” PhD diss., Kassel, 1997, vol. 1.

- Hausmann exhibited five works in the exhibition Ersten Schwarz-Weiß Ausstellung at the Neue Kunst Gallery, Munich, early in 1914.

- The article focuses on Carlo Carrà, Luigi Severini, Ardengo Soffici and Umberto Boccioni. See Theodor Däubler, “Futuristen,” Die neue Rundschau 27 (1916): 414–20.

- Theodor Däubler, “Henri Rousseau,” Die weißen Blätter 3, no. 1: 239–43. Däubler proposed a book on Rousseau to the publishing house Valori Plastici in 1920.

- Theodor Däubler, “Georg Gross [sic],” Die weißen Blätter 3, no. 4: 167–70.

- In 1915 Däubler said to Klee: “You are a futurist temperament. You belong to a futurism linked to the German cultural tradition. I’m a futurist too, but I also write verses.” See Paul Klee, Tagebücher. 1898–1918 (Cologne: DuMont Schauberg 1957), 319.

- On Grosz’s collectors and market, see Dieter K. Gessner, “Avantgarde und Kunstmarkt. Der Zeichner George Grosz in der Weimarer Republik,” Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 55, 2015: 343–72.

- Theodor Däubler, “George Grosz,” Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung 1 (November 1918): 153.

- George Grosz, “Kaffeehaus,” Neue Blätter für Kunst und Dichtung 1 (November 1918): 155.

- In the same months, Däubler was working with Klee on a similar artistic and literary project, the illustrated book Mit Silber Sichel, which unfortunately was never published. On this particular project, see Wolfgang F. Kersten, “Von der Kosmogonie zum Ikonoklasmus,” Zwitscher-Maschine. Journal on Paul Klee / Zeitschrift für internationale Klee – Studien 6 (2018): 4–29.

- Däubler published a short history of modern art in Valori Plastici: vol. 1 (1919), “Nostro retaggio” (Our Heritage), nos. 6–10 (June–October): 1–5; “Nostro retaggio (parte II),” nos. 11–12 (November–December): 6–9; vol. 2 (1920): “Nostro retaggio (parte III),” nos. 1–2 (January–February): 14–19; “Nostro retaggio (parte IV),” nos. 3–4 (March–April): 36–38; “Nostro retaggio (parte V–fine),” nos. 5–6 (May–June): 56–58; “Henri Rousseau,” nos. 9–12: 98–100; vol. 3 (1921): “Marco Chagall,” no. 1: 11–13; and “Marc,” no. 2: 40–41.

- Theodor Däubler, “Georg Grosz,“ Das junge Deutschland 2 (1919): 176.

- Leopold Zahn, “George Grosz-Paul Klee,” Valori Plastici 2, nos. 7–8 (July–August 1920): 88–89.

- Around 1920 in Germany the subject had particular relevance. See Leopold Zahn, “Über den Infantilismus in der neuen Kunst,” Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 3 (March 1920): 5–7. In the same period, it was studied also by Gustav F. Hartlaub, see his “Der Genius im Kinde,” Kunst und Jugend 1, no. 3, 1921: 41–44.

- On the early contact between de Chirico, Enrico Prampolini, Julius Evola, and Zurich Dada, and on the fortune of Dadaism in Italy, see the series of articles by Enrico Crispolti, “Dada a Roma. Contributo alla partecipazione italiana al Dadaismo,” Palatino 12, no. 1 (January–March 1968): 51–56; no. 2 (April–June 1968): 187–96; no. 3 (July–September 1968): 294–99. See also Valeria Paoletti, Dada in Italia. Un’invasione mancata, PhD diss., Viterbo, 2009.

- See Maria Elena Versari, “‘Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor’: Expectations, Misunderstandings, and Appropriations of Pittura Metafisica Among the 1920s European Avant-Garde,” in this issue.

- Leopold Zahn, “Dadaismus oder Klassizismus?,” Der Ararat, no. 4 (April 1920): 50–52. On the differences between Dadaists, see also Kurt Schwitters, “Merz, ‘?,’” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1921): 3–9.

- See Joan Weinstein, The End of Expressionism: Art and the November Revolution in Germany, 1918–19, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 1990.

- See idem, 231–32.

- Hans Goltz, “Der ‘neue’Ararat,” Der Ararat, no. 1 (January 1920): 1. This might be interpreted as a consequence of the January uprising in Berlin (Spartakusaufstand, January 1919) and of the Bavarian Soviet Republic (April–May 1919).

- On Carl Einstein’s involvement with Berlin Dada, see Charles W. Haxthausen, “Bloody Serious: Two Texts by Carl Einstein,” October 105 (Summer, 2003): 105–18.

- For further reading, see Brigid Doherty, “The Work of Art and the Problem of Politics in Berlin Dada,” October 105 (Summer 2003): 73–92.

- John Heartfield and George Grosz, “Der Kunstlump,” Der Gegner 1, nos. 10–12 (April 1920).

- Theodor Däubler, Ferdinand Hardekopf, and Titus Tautz, “Distanzierung vom ‘Club Dada’ und Verwahrung gegen des Mißbrauch ihrer Namen,” in Berliner Börsen-Courier, February 2, 1918: 5. See also Elisabeth Laur, “Theodor Däubler,” in “Porträits von Künstler seiner Zeit,” in Ernst Barlach, Theodor Däubler. Die Welt versöhnt und übertönt der Geist, ed. Volker Probst and Helga Thieme (Güstrow: Ernst Barlach Stiftung, 2001), 19–24; and Karin Füllner, Dada Berlin in Zeitungen. Gedächtnisfeiern und Skandale (Siegen: Universität-Gesamthochschule-Siegen/MuK, 1986), 15–18.

- George Grosz, Briefe 1913–1959, ed. Herbert Knust (Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1979), 72.

- Richard Huelsenbeck, En avant Dada. L’histoire du dadaïsme (Paris: Les presses du reel, 2005), 33.

- Theodor Däubler, Im Kampf um die moderne Kunst (Berlin: Erich Reiss Verlag, 1918), 36.

- Harry Graf Kessler, “Tagebucheintragung,” March 23, 1919, in John Heartfield, Der Schnitt antlang der Zeit (Dresden: VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1981), 34.

- Harry Graf Kessler, “Tagebucheintragung,” March 27, 1919, in ibid.

- Theodor-Däubler-Archiv, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 587. Meanwhile, Hannah Höch, in her photomontage Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic, 1919), made fun of Däubler by placing his head atop a fat baby’s body.

- See Berlinische Galerie, ed., Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, 1919–1920, Archiv-Edition, vol. 1, no. 2 (Berlin: Berlinische Galerie and Argon, 1989), 632.

- See “Dada in Europa,” in Der DADA, no. 3 (April 1920): 437.

- Letter from Tristan Tzara to Richard Huelsenbeck, August 22, 1919. See Dennis Crockett, German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder 1918–1924 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 45–46. Huelsenbeck and Tzara were promoting de Chirico’s work in the review Dada as early as July 1917, when a reproduction of The Evil Genius of a King appeared in its second issue.

- See Haxthausen, “Bloody Serious,” 118. On Carl Einstein’s interest in de Chirico, see C. Einstein, “Giorgio de Chirico,” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration 31, no. 4 (1928): 259–66; and his introduction to the exhibition catalogue Giorgio de Chirico (Berlin: Galerie A. Flechtheim, 1930).

- Carl Einstein, “Rudolf Schlichter,” Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 4 (April 1920): 105–08.

- On his approaches to Dadaism, see Patrick Lhot, L’indifférence créatrice de Raoul Hausmann. Aux sources du dadäisme (Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaire de Provence, 2013).

- Konstantin Umansky, “Der Tatlinismus oder die Maschinenkunst,” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 10.

- Raoul Hausmann, “Rückkehr zur Gegenständlichkeit in der Kunst,” in Dada Almanach, ed. Richard Huelsenbeck (Berlin: Erich Reiss Verlag, 1920), 147–51. “You should read the pages 147 to 151 of the Dada-Almanach to the people in Rome.” Letter from Johannes Baader to Hannah Höch, February 6, 1920, in Berlinische Galerie, Hannah Höch, 716.

- Hausmann, “Rückkehr zur Gegenständlichkeit in der Kunst,” 150.

- Ibid., 151.

- See März, “Republikanische Automaten. George Grosz und die Pittura metafisica,” 146–56.

- As is well known, the metaphor of the machine was widespread in Dada works (e.g., Francis Picabia, Max Ernst, Jefim Golyscheff, Rudolf Schlichter, and John Heartfield). On this subject, see Matthew Biro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

- Raoul Hausmann, George Grosz, John Heartfield, and Rudolf Schlichter, “Die Gesetze der Malerei,” manuscript copy dated September 1920, published in Berlinische Galerie, Hannah Höch, 698. For an analysis in detail of this Manifesto, see März, “Republikanische Automaten,” 147.

- Hausmann et al., “Die Gesetze der Malerei,” 698.

- This was part of a series of watercolors realized by Grosz for Hans Goltz’s gallery. For an iconographic comparison of this series of watercolors by Grosz and works by de Chirico and by Carrà, see März, “Republikanische Automaten.”

- Biro, The Dada Cyborg, 115.

- The monograph included around twenty illustrations, some in color. See 12 Opere di Giorgio de Chirico precedute da giudizi critici di Soffici, Apollinaire, Louis Vauxcelles, Raynal, Jacques-Emile Blanche, Roger Marx Papini, Carrà, Etienne Charles ([Rome]: Valori Plastici, [1919]). See also Berlinische Galerie, Hannah Höch, 632. The references to de Chirico are multiple because, as can be apprehended from a review that appeared in Das Kunstblatt, by February 1920 the illustrated de Chirico monograph edited by the Valori Plastici publishing house was already available in Germany. See Das Kunstblatt 4, no. 2 (February 1920).

- George Grosz, “Zu meinen neuen Bildern,” Das Kunstblatt 5 (January 1921): 11–14, 16.

- Ibid., 14.

- George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, Otto Dix, Max Dungart, Hannah Höch, Ernst Krantz, Franz Mutzenbecher, Thomas Ring, Rudolf Schlichter, Georg Scholz, Willy Zierath, “Offener Brief an die Novembergruppe,” Der Gegner 2, Nos. 8–9, 299. See Dennis Crockett, German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder 1918–1924 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 54—56.

- Benson, Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada, 144.

- See Ghislain Lauverjat, “Vision optophonique (1919–1971). Raoul Hausmann et les sources scientifiques de l’optophonie,” in Timothy O. Benson, Hanne Bergius, and Ina Blom, eds., Raoul Hausmann et les avant-gardes (Paris: Les Presses du réel, 2015), 169–94.

- George Grosz, letter to Raoul Hausmann, Berlin, December 13, 1921, in Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, 1919–1920, Archiv-Edition, vol. 1, no. 2: 34–35.

- It should not be omitted that by 1924, the Valori Plastici publishing house had put out one of Grosz’s first monographs in Italian, edited by Däubler’s friend Italo Tavolato. Omitting any reference to his “metaphysical” turn, the art critic focused on a sociological analysis of Grosz’s satirical drawings against “bourgeois species,” and he made no references to Dadaism or communism. See I. Tavolato, Georg Grosz (Rome: Valori Plastici, 1924), 12–14.

- Oskar Schlemmer, teacher at the Bauhaus since November 1919, also reflected upon this peculiar “constructive” interpretation of the Metaphysical paintings and was deeply influenced by Carrà. See Karin V. Maur, “Carrà und Deutschland,” 15–17; and Crockett, German Post-Expressionism, 136–37.

- Katrin Lochmaier, “Die Galerie ‘Neue Kunst – Hans Goltz’ München 1912–1927,” 103–10.

- Dieter K. Gessner, “Avantgarde und Kunstmarkt. Der Zeichner George Grosz in der Weimarer Republik,” Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 55 (2015): 367.

- George Grosz, in Paul Westheim, “Ein neuer Naturalismus? Eine Rundfrage des Kunstblatts,” Das Kunstblatt 9 (September 1922): 382–83.

- El Lissitzky and Hans Arp, Die Kunstismen – Les ismes de l’art / The Isms of Art 1924–1914 (Zurich: Erlenbach; München: Eugen Rentsch Verlag, 1925).

- Theodor Däubler, “Neueste Kunst in Italien,” Der Cicerone 12, no. 9 (May 1920): 349–55; and Jahrbuch der jungen Kunst (1920): 141–46. In 1921, he published “Moderne Italiener,” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 1: 49–53.

- On the exhibition, see Dieter Scholz, “Faschistische Bilder in der Nationalgalerie? Italienische Gegenwartskunst in Berlin 1921–1933,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 53 (2011): 131–46. In Italy, the exhibition project is mentioned in a letter that Carrà writes to Soffici on November 29, 1919. See Messina, “L’Espressionismo nell’area di ‘Valori Plastici.’”

- Theodor Däubler, letter to Hermann Schmitt, December 2, 1920, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Theodor-Däubler-Archiv.

- “Umschau,” Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 2 (1919): 186.

- Theodor Däubler, letter to Ludwig Justi, December 25, 1920, Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin, Nachlass Ludwig Justi, 531.

- See Ludwig Justi, letter to Mario Broglio, February 12, 1921, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Archiv, 1163/20: 128/129.

- Mario Girardon, letter to Ludwig Justi (March 8, 1921), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Archiv, 1163/20: 130.

- See Dieter Scholz, “Faschistische Bilder in der Nationalgalerie? Italienische Gegenwartskunst in Berlin 1921–1933,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 53, (2011): 131–46. On the works included in the exhibition, see Emanuele Greco, “The Origins of an Ambiguity: Considerations of the Exhibition Strategies of Metaphysical Painting in the Exhibitions of the Valori Plastici Group, 1921–22,” in this issue.

- Carlo Carrà, “Arti Plastiche,” I.I.I. 5, no.1, series C (January 1921): 9.