Introduction

“Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor”: Expectations, Misunderstandings, and Appropriations of Pittura Metafisica Among the 1920s European Avant-Garde

This essay is devoted to a subject that has been overlooked by scholars until now, namely, a peculiar moment of confluence among Futurism, Pittura Metafisica and Dadaism and the impact it had on the 1920s avant-garde. Focusing on the reception of Pittura Metafisica in avant-garde circles outside Italy, it retraces the interpretations of the Italian trend, highlighting the effects that a series of misunderstandings of its theoretical and ideological positions had on the aesthetic ideas of several avant-garde artists. It addresses the way in which the image of Pittura Metafisica was conflated with the legacy of Futurism and with the limited information about Constructivism coming out of Russia. This unstable conceptual merger, in turn, resulted in a new wave of reflections that compelled major German Dadaists such as Georg Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, and Hannah Höch to reconsider the role of realism and visual distortion within a specifically modernist idiom. Finally, this essay will reassess the writings of Aldo Camini, the least studied among the avant-garde personas created by De Stijl’s Theo van Doesburg. By reconstructing the reception of Pittura Metafisica abroad, my work aims to show the central role that this movement played in the debates on avant-garde identity in the 1920s.

“Dada Marshall and Propagandada” George Grosz and “Metapolitiker” Theodor Däubler: Metafisica and Politics in Berlin, 1920

The aim of this paper is to investigate the relationship of the Berlin-based artist George Grosz and the eclectic poet and art critic Theodor Däubler with reference to their mutual interest in Italian modern art, from Futurism to Metafisica. Through the prism of their interaction, it is possible to follow the double fortune of Metafisica in Berlin in the year 1920 thanks to the intricate network of contacts and collaborations that, mostly through art magazines, facilitated the circulation of images by de Chirico and Carrà as part of a shared international visual culture, open to multiple stylistic and ideological interpretations.

The Origins of an Ambiguity: Considerations on the Exhibition Strategies of Metaphysical Painting in the Exhibitions of the Valori Plastici Group, 1921–22

The magazine Valori Plastici, published in Rome between 1918 and 1922 under the direction of Mario Broglio, had a decisive role in the European artistic context after WWI. It presented the works of an innovative group of Italian artists including Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Giorgio Morandi, Alberto Savinio, Arturo Martini and Edita Walterowna von Zur Muehlen, who worked to rediscover the roots of their own artistic languages in the Italian Medieval and Renaissance traditions. The magazine was a remarkable medium for the international spread of Metaphysical painting, that took place when the artists more connected to this style outdistanced themselves from it in favor of a more naturalistic pictorial language. Moreover, Valori Plastici presented metaphysical painting both as an innovative language of the avant-garde and as well as a language that followed the Italian artistic tradition. The proposal highlights this ambiguous interpretation of Metaphysical painting given by Valori Plastici. Analyzing the exhibition activity of Valori Plastici, with an emphasis on the 1921 tour in Germany, and the participation at the Fiorentina Primaverile in Florence in 1922, it will show how Broglio intended to present Metaphysical painting during the exhibitions of Valori Plastici, and how it was a strategic move to describe the language of Metaphysics to the public in different ways.

Italienspielerei: Italian and German Painting from Metafisica to Magischer Realismus

The relationships between Italian pittura metafisica and German Neue Sachlichkeit have mostly been described in two ways: as the “history of an influence,” referring to the knowledge of De Chirico and Carrà among Grosz and other painters working in Munich and Berlin in 1919; or as “similar paths,” pointing out the autonomy of German early objectivity of Davringhausen or Schrimpf. The aim of this paper is to show that the relationship between these two modes of expression is, in fact, biunivocal, underlining figurative intercourses on both sides of their transnational encounter. I will consider the reception of the exhibition “Das Junge Italien” (1921) that showed postwar Italian art in Germany. Theodor Däubler’s writings and the early contributions by Franz Roh recognized how Valori Plastici group was linked to the rising idea of “objectivity” in Germany. Then I will focus on the category of Magic Realism elaborated by Roh in his important 1925 book Nach-Expressionismus, in which Metaphysical artworks play a central role as the roots of many features of the new painting. Many Italian artists were fascinated by metafisica as well as by contemporary German art. This mutual relationship can explain the internal coherence of Roh’s Magischer Realismus, shedding light to the lasting value of Metaphysical international language.

Metaphysical Writing and the “Return to Order”: Artistic Theorization and Modernist Magazines Between 1916 and 1922

This article looks at the extensive theorization and critical activity carried out by the artists involved in the Metaphysical movement between 1916 and 1922, with particular reference to the writings of Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. Focusing primarily on the magazines La Brigata, La Raccolta, Valori plastici, La Ronda, Il primato artistico italiano and Il Convegno, published in the crucial years between World War I and the rise of Fascism (with the exception of Il Convegno, which was published between 1920 and 1939), the article explores how these writings contributed to the theorization of Metaphysical Art and it considers their essential role in shaping the artistic debate in Italy in the years of the so-called “return to order.” It assesses the role played by Metaphysical writing in the demise of avant-garde aesthetics and in the promotion of a revision of the relationship between art and politics, which saw a reconceptualization of the classical as central to the redefinition of postwar national culture. It discusses some of the aesthetic and ideological implications attached to the redefinition of the idea of the classical in the postwar context, with particular reference to the centrality attributed to Italy in the renewal of European art.

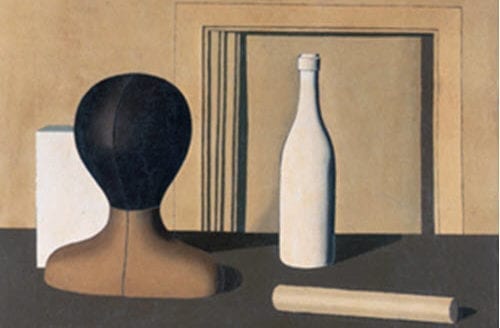

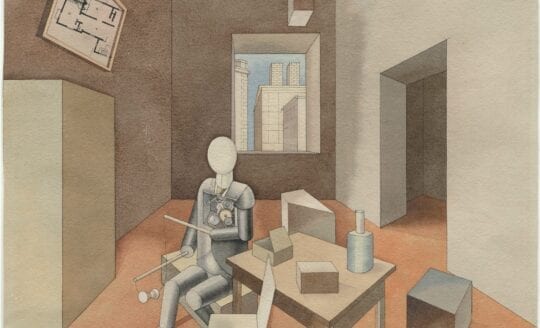

Metaphysics into Everyday Life: Traces of Metaphysical Painting in Italian Decorative Arts of the 1920s

This study addresses the process through which, during the 1920s, Metaphysical painting was appropriated by some Italian decorators. I assume that they actively responded to the novelties that were introduced by artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, and Giorgio Morandi, reflecting upon them and, when considered effective, adapting them for their own purposes. By doing so, they contributed to the definition of a particular Italian visual culture, which today we associate with the interwar period, and which had Metaphysical painting as one of its main references.

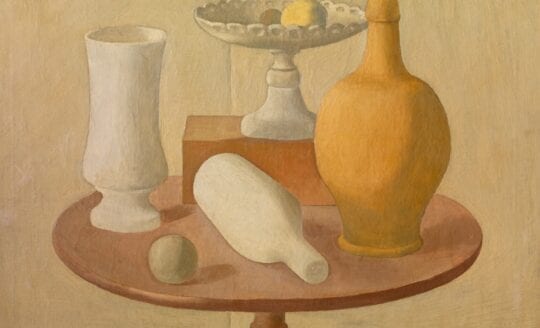

“Intellectual lucubrations”: Lamberto Vitali, Giorgio Morandi, and Metaphysical Art

Why didn’t Lamberto Vitali praise the artistic products of Morandi’s metaphysical phase as he did for works completed at other moments of the artist’s career? In Vitali’s writings on Morandi – in, for example, the different editions of his catalogue raisonné – the art historian doesn’t explicitly declare a preference. However, there is an evident change in the way he discusses the works of the artist’s metaphysical years (1918–1919). For instance, when he writes about the artist’s landscapes painted in the following years, between 1921 and 1925, he claims that they have a “tender sweetness in the representation, very far from the intellectual lucubrations of the Metaphysical Still Life.” This apparently banal and marginal question allows us, on the contrary, to consider Vitali’s reading of Morandi’s œuvre with a far broader perspective for which it becomes pivotal to take into consideration the collecting taste of the time. Through this reading of Vitali’s texts and of Morandi’s images, as well as an analysis of the contemporary market tendencies, it becomes possible to define the cultural reasons underlying Vitali’s taste.

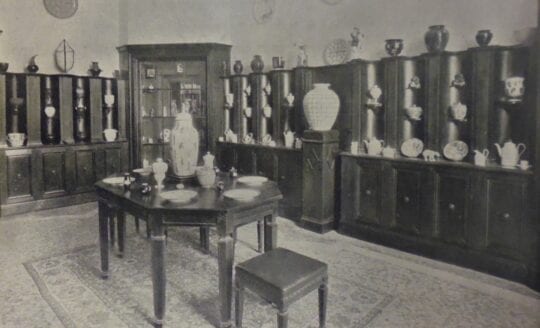

Shaping an Identity for Italian Contemporary Art During the Interwar Period: Rino Valdameri’s Collection

Rino Valdameri (Crema 1889 – Milan 1943) was a lawyer, patron, collector, and great promoter of Italian art, who in the years between the two wars built up in Milan one of the most conspicuous collections of modern paintings and sculptures, playing a central role within the system of Italian art and collectors’ market. Valdameri’s initiation into the patronage world took place sometime around 1919, almost as a consequence of his political interests and involvement in the Regime: through his friend, Gabriele D’Annunzio, he began to deal in art and made his debut curating the great edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy with illustrations by painter Amos Nattini. In two decades, he assembled more than 450 artworks, which mostly includes artists Valdameri considered to be at the forefront of international modern art, such as Giorgio de Chirico. Through his collection, Valdameri aimed to contribute to shape an Italian contemporary art as well as create a national, and international, art market for it, so that particularly important were Valdameri collaborations with art dealers and galleries in Milan, such as the Milione Gallery and the Milano Gallery. In this article I partially reconstruct the history of this large collection, the collecting taste of Valdameri, as well as his relationship with influential figures of the Italian political and artistic scene in the interwar years.

“Chiricos checked”: Metaphysical Art in James Thrall Soby’s Notebooks, Spring 1948

This essay concerns the travel notebooks that James Thrall Soby, Head of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the MoMA, filled out in the spring of 1948 during his trip to Italy, accompanied by the director of the museum collections Alfred H. Barr, Jr. The purpose of this trip was to visit the most significant art collections, both private and public, in order to select contemporary artworks for inclusion in Twentieth-century Italian Art, which would be, after the fall of Fascism, the first major North American exhibition to focus entirely on Italian modern art. Relying on the most recent studies on these newly-discovered notebooks, now preserved in the MoMA Archives, my essay will examine and further discuss a particular, arguably predominant aspect of this precious documentary material, enriched by some sketches. It is the importance given, in the great New York show, to the so-called “Metaphysical School,” and to its key protagonists Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Giorgio Morandi, focussing chiefly on Soby’s artistic sensibility and critical acumen in extricating himself from the multifaceted panorama of Italian art collecting of the 1940s.

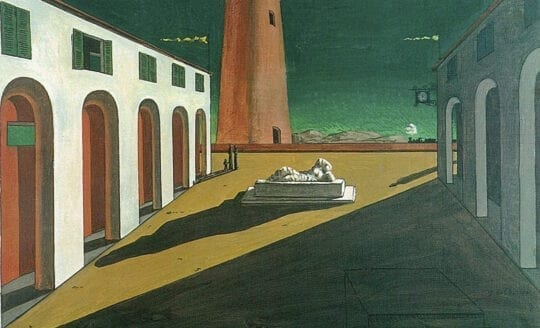

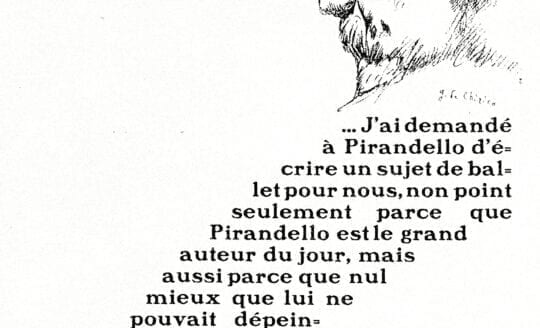

“Sentimento del contrario”: Giorgio de Chirico’s Irony and Luigi Pirandello’s Umorismo

The architectural language and color scheme of de Chirico’s Piazze Italiane is codified in terms of national identity. They reveal the artificial character of the young Italian state, dealing with the precarious hiatus between the pathetic and the ridiculous, and suggesting that the construct named “Kingdom of Italy” was, in reality, insubstantial. De Chirico shared this interest, including its ironic refraction, with Luigi Pirandello who is widely acknowledged as a writer-philosopher, just like de Chirico considered himself a painter-philosopher. Through a comparative analysis of Pirandello’s 1908 essay L’umorismo, and the paintings and writings of de Chirico’s metaphysical period, my paper aims to map out an elective affinity between the painter’s aesthetics and the author’s theoretical viewpoint. With similar diction the two specify an Italian sense of tragedy as a precondition for “humorist” art. Most strikingly, Pirandello’s rejection of logic reads like an anticipation of de Chirico’s theory of the “aspetto spettrale,” made visible by the metaphysical artwork. Hence, this paper is an attempt to enlarge the range of de Chirico’s spiritual sources, often one-sidedly identified with German philosophy (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche), by an Italian element, which may have had an even greater impact on his visual thinking.

Italian Art in the 1920s and 1970s: Affinities and Differences

This paper establishes some affinities between the creations of the 1920s (i.e. including Metapysical painting, Novecento, “rappel á l’ordre,” etc.) and those produced nearly sixty years after, in the 1970s. As is well known, artists of the 1920s – and especially the protagonists of Futurism (i.e. Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Mario Sironi, etc.), the decade’s most advanced avant-garde movement – primarily concerned themselves with a process of abandonment, of inverting their attention from the present in order to retrieve the past and recuperate the masterpieces found in museums. This retrospective impulse resulted from the influence of Giorgio de Chirico who, wholly confident in proceeding down his own artistic path, wished to conceive “originary” solutions (i.e., connected to the origins), rather than “original” ones. The same creative impetus laid at the foundation of Arte Povera, a movement established decades later whose founder, Germano Celant, in fact, was tempted to declare the movement a “New” Futurism. From this very advanced group there emerged yet another contrary spirit, represented in the work of Giulio Paolini, Luciano Fabro, and especially the young Salvo. Unlike those associated with Arte Povera, this last artist refused to condemn color and opted instead to introduce an exceptionally brilliant “palette,” that brought to mind colored images on TV and, especially, the naive world of cartoons. Almost immediately after Salvo, Luigi Ontani embarked on this same path: his colored photographs seemed dedicated to resurrecting the historical (or folkloric) figures contained in museums. Later another rich group of artists naturally emerged, to which I myself gave the name of Nuovi-Nuovi, built on the innovations of these two pioneers; however, almost simultaneously, another group (including Carlo Maria Mariani and Stefano Di Stasio) embraced the label of “anachronism” wherein the prefix “ana” proclaims going “á rebours” through the stream of time. Finally, in such a propitious situation, a third group was born: the Transavantguard (including Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, and Mimmo Paladino). Here again the prefix “trans” proclaims the artists’ refusal to respect the normal trend of time. All these very stimulating groups considered themselves to be under the protection of an eternally “revenant” de Chirico, who, while continuing his very coherent search of mythical origins, was ready to accept newer times, consisting in a spirit of lightness, of enchanted colorism, of irony, and of all aspects that would ultimately come to be considered deeply intrinsic to so-called postmodernism.