Previous Issues

Featured Articles

1963, “An Exhuming Job:” Medardo Rosso, Margaret Scolari Barr, and the MoMA Exhibition*†

The article revolves around the rediscovery of Medardo Rosso in the United States in the early 1960s, with a special focus on the scholarship of Margaret Scolari Barr and the exhibition organized by Peter Selz at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1963. Scolari Barr was thoroughly committed to the reappraisal of Rosso’s art as a pioneering model of modernism, thus positioning the Italian sculptor in the lineage of Western modern and contemporary art. By analyzing her contributions on Rosso—primarily the monograph published in 1963—I aim to demonstrate that Scolari Barr was a scholar and a critic in her own right, who asserted her critical voice through the study on the artist. The book was supported by the organization of a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which is reconstructed in the appendix of the article, with as much information as I have been able to find thus far. The relevance of the exhibition lies in the possibility to investigate the early fortune of Rosso in the American art market and evaluate how the appreciation of his art fit within the taste of major collectors and museums overseas. The double initiative of Scolari Barr’s book and the MoMA exhibition marks a watershed moment in informing the international reception of Medardo Rosso and defining his legacy.

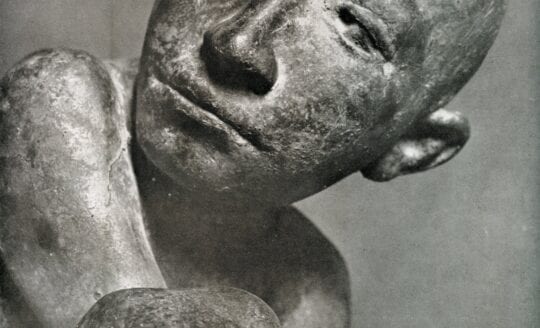

Photographing Sculpture: A Comparison between Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù from 1930 to 1950

This essay examines the crucial role that photography played in the affirmation and critical interpretation of Marino Marini (1901-1980) and Giacomo Manzù (1908-1991), two of Italy’s foremost modernist sculptors. Through a close comparison of photographs published in books, art journals, and magazines, the author demonstrates how the choices that photographers make when portraying sculpture greatly influence the legibility of a work. The importance of photographic reproduction became particularly evident in Italy during the 1940s: given the constraints that World War II imposed on the travel of artworks and the organization of art exhibitions, the circulation of photographs was a pivotal instrument in establishing the reception of Marini’s and Manzù’s sculptures, with significant reverberations in the postwar era. The photographers’ choices in terms of angle, cropping, backgrounds, and lighting thus provided a first, critical reading that is here thoroughly studied over the course of three decades.

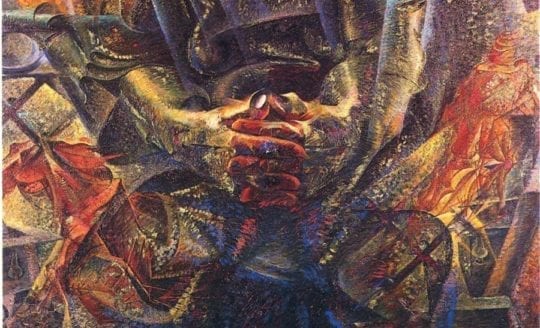

Italienspielerei: Italian and German Painting from Metafisica to Magischer Realismus

The relationships between Italian pittura metafisica and German Neue Sachlichkeit have mostly been described in two ways: as the “history of an influence,” referring to the knowledge of De Chirico and Carrà among Grosz and other painters working in Munich and Berlin in 1919; or as “similar paths,” pointing out the autonomy of German early objectivity of Davringhausen or Schrimpf. The aim of this paper is to show that the relationship between these two modes of expression is, in fact, biunivocal, underlining figurative intercourses on both sides of their transnational encounter. I will consider the reception of the exhibition “Das Junge Italien” (1921) that showed postwar Italian art in Germany. Theodor Däubler’s writings and the early contributions by Franz Roh recognized how Valori Plastici group was linked to the rising idea of “objectivity” in Germany. Then I will focus on the category of Magic Realism elaborated by Roh in his important 1925 book Nach-Expressionismus, in which Metaphysical artworks play a central role as the roots of many features of the new painting. Many Italian artists were fascinated by metafisica as well as by contemporary German art. This mutual relationship can explain the internal coherence of Roh’s Magischer Realismus, shedding light to the lasting value of Metaphysical international language.

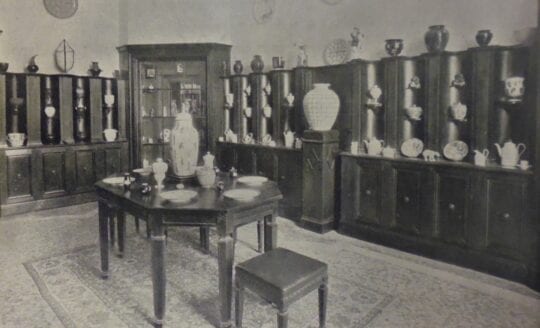

Metaphysics into Everyday Life: Traces of Metaphysical Painting in Italian Decorative Arts of the 1920s

This study addresses the process through which, during the 1920s, Metaphysical painting was appropriated by some Italian decorators. I assume that they actively responded to the novelties that were introduced by artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, and Giorgio Morandi, reflecting upon them and, when considered effective, adapting them for their own purposes. By doing so, they contributed to the definition of a particular Italian visual culture, which today we associate with the interwar period, and which had Metaphysical painting as one of its main references.

“Positively the only person who is really interested in the show”: Romeo Toninelli, Collector and Cultural Diplomat Between Milan and New York

Romeo Toninelli was a key figure in the organization of Twentieth-Century Italian Art, and given the official title of Executive Secretary for the Exhibition in Italy. An Italian art dealer, editor, and collector with an early career as a textile industrialist, Toninelli was not part of the artistic and cultural establishment during the Fascist ventennio. This was an asset in the eyes of the James Thrall Soby and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who wanted the exhibition to signal the rebirth of Italian art after the presumed break represented by the Fascist regime. Whether Toninelli agreed with this approach we do not know, but he played a major part in the tortuous transatlantic organization of the show. He acted as the intermediary between MoMA curators and Italian dealers, collectors, and artists, securing loans and paying for the shipping of the artworks. He also lent several works from his collection, and arranged for the printing of the catalogue. A recent collector and gallery owner, Toninelli was mistrusted by many Italian critics and collectors, who suspected him of having commercial motives. Yet he arranged the practical side of the operations while intervening little in the decision-making about which artists to include – exactly as MoMA wanted.

Analyzing Toninelli’s role in organizing the pioneering display of Italian modernism at MoMA provides important insights into transatlantic cultural exchanges between Italy and the U.S. in the postwar period, and illuminates critical fractures of the Italian art system in the aftermath of Fascism. Were native-born critics and artists obliged to hand the narrative of modern Italian art over to outsiders who had not been compromised by the Fascist regime, or were they entitled to an account independent from the modernist vulgate promoted by MoMA?

“Friendly Competition”: A Network of Collecting Postwar Italian Art in the American Midwest

Collecting art is usually seen as an individual occupation, motivated by personal passion, desire to possess, and economic investment. This paper suggests that there are social aspects of collecting that need to be considered as well. These aspects can lead to a form of “friendly competition” among local collectors. This is evident in the case of St. Louis and the collecting of postwar Italian art. Through interviews with family members and research into archival materials, this paper traces the identities of collectors (Pulitzer, Weil, Shoenberg, May, and Bernoudy) and examines the mechanisms through which productive rivalries arose. It concentrates on the collections of the Kemper Art Museum and the Saint Louis Art Museum, where one finds similar-looking works by Alberto Burri, Afro, and Marino Marini, made in the same years and bought by local collectors in the same period.

What were the relationships and connections that developed between St. Louis collectors of postwar art? How did this web develop into a community or social group, and how did this lead to donations of works to local museums? What were the relationships between these collectors and the 1949 MoMA exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art and its organizers? How did MoMA shows, prepackaged for further exhibition in the Midwest, influence collectors’ tastes? How did travel abroad to exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale affect acquisition habits? Whose opinion did the collectors trust and which dealers did they buy from? Such questions and their ramifications are discussed before the paper concludes with a consideration of the process through which St. Louis collectors were identified in Harold Rosenberg’s 1965 Esquire article on tastemakers in the field of contemporary art.