“Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor”: Expectations, Misunderstandings, and Appropriations of Pittura Metafisica Among the 1920s European Avant-Garde

Maria Elena Versari Maria Elena Versari Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

This essay is devoted to a subject that has been overlooked by scholars until now, namely, a peculiar moment of confluence among Futurism, Pittura Metafisica and Dadaism and the impact it had on the 1920s avant-garde. Focusing on the reception of Pittura Metafisica in avant-garde circles outside Italy, it retraces the interpretations of the Italian trend, highlighting the effects that a series of misunderstandings of its theoretical and ideological positions had on the aesthetic ideas of several avant-garde artists. It addresses the way in which the image of Pittura Metafisica was conflated with the legacy of Futurism and with the limited information about Constructivism coming out of Russia. This unstable conceptual merger, in turn, resulted in a new wave of reflections that compelled major German Dadaists such as Georg Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, and Hannah Höch to reconsider the role of realism and visual distortion within a specifically modernist idiom. Finally, this essay will reassess the writings of Aldo Camini, the least studied among the avant-garde personas created by De Stijl’s Theo van Doesburg. By reconstructing the reception of Pittura Metafisica abroad, my work aims to show the central role that this movement played in the debates on avant-garde identity in the 1920s.

In January 1920, the Munich-based journal Der Ararat published an essay on Vladimir Tatlin’s art by the Soviet art critic and future diplomat Konstantin Umanski.1 This unillustrated text remained for the next two years one of the only sources on Constructivism available to Western artists and critics. Umanski wrote:

Art is dead. Long live art. The machine art with its construction and logic, its rhythm, its components, its material, its metaphysical spirit. The art of the “counter-reliefs.” This art considers no type of material to be unworthy: wood, glass, paper, sheet metal, screws, nails, electric armatures, glass fragments to cover surfaces, the insertion of mobile parts, and so forth.2

Historians of Constructivism have referred to this essay extensively because of the important role it played in shaping Western artists’ expectations of the new Soviet trend. Scholars of Dada have stressed its immediate repercussions on German Dada. Just a few months after its publication, in fact, George Grosz and John Heartfield exhibited a placard at the 1920 Dada Fair in Berlin celebrating the rise of the “new machine art of Tatlin.” Directly referencing Umanski’s passage cited above, the placard read: “Art is dead. Long live Tatlin’s machine art” (figure 1). The Dadaists’ embrace of Tatlin via Umanski reflected their drive to move away from what they viewed as the idealist mire of Expressionism. As Timothy Benson has explained: “While a profound disillusionment among the Expressionists was producing somber obituaries, Raoul Hausmann appeared triumphant [… when he wrote] in the third issue of Der Dada: ‘Dada is the full absence of what is called Spirit [Geist]. Why have Spirit in a world that runs on mechanically?’”3

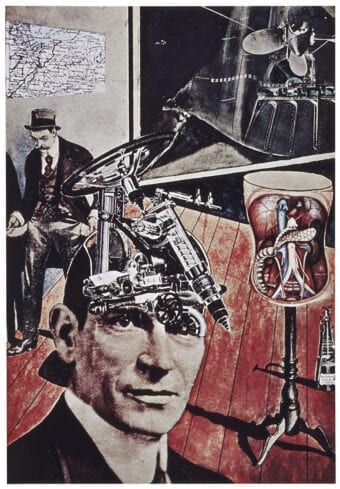

What scholars have failed to notice, however, is the peculiar confluence of other artistic trends in the debate surrounding Tatlin’s mysterious art, and in particular, the way in which its critical reception was intertwined with that of another trend making its way to Germany at the time: Pittura Metafisica. The influence of Italian art is difficult to miss when we look at the collages that Hausmann himself decided to show at the Dada Fair, such as Tatlin lebt zu Hause (Tatlin at Home, 1920; figure 2) and Dada siegt! (Dada Triumphs!, 1920).4 In these works, photographic illustrations cut from magazines (human figures, propellers, the steering wheel system of an automobile, anatomical torsos, typewriters, etc.) are glued along with sections of geographic maps onto a watercolor background reproducing the unstable perspectival setting of a Chirico–esque room. The photographic images were carefully inserted by Hausmann into objects he painted within the room, creating the illusion of a somewhat unstable, but overall visually coherent three-dimensional setting. Some of these cut-outs were placed within fictional picture frames on the walls or on an artist’s easel; others were laid on the distinctive wooden floorboards that characterize so many of Giorgio de Chirico’s interiors.

A few art historians have noticed, in passing, the German Dadaists’ stylistic appropriations of de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. In her influential monograph “Dada Triumphs!”: Dada Berlin, 1917–1923 (2003), Hanne Bergius acknowledges that the Dadaists “took over” a wide array of formal solutions proper to Pittura Metafisica. Dada, in her words, embraced the Italians’ “tendency toward abstraction, spatial illusions of urban constructions, the sobriety of architectural conceptions, geometrical elements, multifocal perspectivism, abrupt vanishing lines that only converged outside the painting, ground planes that suggested depth, the timeless blue sky, and above all the manichino, the staple of pittura metafisica.”5 Bergius’s list of appropriations is impressive, but it is presented rather matter-of-factly, with little analysis aside from the remark that the Dadaists “deprived their anthropomorphous artifacts […] of their aura of the uncanny and the sublime,” and that “in contrast to de Chirico’s enigmatic stage sets, these constructions were meant to refer to real life.”6

It would be impossible in the limited space of this essay to fully address the question of what constitutes “real life” in Dada and Pittura Metafisica. But it is important to note that, even if we were to agree with Bergius that there exists a thematic discrepancy between the two movements, this does not undermine the fact that the most striking element characterizing German Dada circa 1919–20 is the extent of its stylistic appropriation from another artistic group. Scholars have systematically failed to acknowledge the importance of this exhibited stylistic camouflage, which in turn has blurred our understanding not only of German Dada’s self-staging strategies but also of the impact of Pittura Metafisica itself. Carrà and de Chirico might indeed have played a role as significant as Tatlin’s on the international avant-garde in the early 1920s.

In his book German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder (1999), Dennis Crockett touches on the reluctance of scholars to acknowledge Pittura Metafisca’s influence on Dada: “As contradictory as it might seem today, the evidence at the Dada fair suggests that the Dadaists associated pittura metafisica with Constructivism.”7 He also quickly dismisses the extent of the Italian influence, once again reverting, like Bergius, to a theoretical disconnect between the two movements: “[T]he Italian theories seemed to have attracted no interest in Germany (how many German artists read Italian?). It was only the duotone images that interested the Germans.”8

I, for one, am not completely convinced that German artists were simply looking at pictures and a-critically copying compositional structures, especially since they would have been hard pressed to focus on the illustrations without at least glancing at the texts, in either German or Italian, that surrounded them. The Italian publications were available to these artists. In the fall of 1920, when Hannah Höch traveled to Italy, Raoul Hausmann gave her his copy of the de Chirico album published by Valori Plastici (1919) as a present.9 And even if the German Dadaists did not read Italian, as Crockett suggests, they surely would have been introduced to the ideas of Valori Plastici by the magazine’s most important German contributor, Theodor Daübler. Before, during, and after World War I, Daübler had mediated between Italian and German modernist cultures.10 In addition to contributing to the Italian journal, he was directly involved in the planning of the Valori Plastici traveling exhibition in Germany, and he gave a lecture at the opening of the show in Berlin in 1921.11

Daübler’s importance for German Dada should not be underestimated. In 1916, he had written the first important articles on George Grosz and Otto Dix, thus officially launching their careers.12 This earned him Grosz’s unabashed friendship as well as the less enviable nickname “Fat Theodor” that he coined for him.13 Daübler’s connection to the Dadaists must have extended beyond Grosz. In the lower section of Hannah Höch’s famous collage Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919),14 we find a series of distorted portraits of members of the Dada group and the phrase “Die Grosse Welt Dada” (The Great Dada World). Among them, Höch glued a photograph of Daübler’s head on top of the gigantic body of a fat baby.15

As we shall see, the critical assessment of Pittura Metafisica in Germany at the time of the Dadaists’ stylistic appropriations provided them with a set of theoretical coordinates that corresponded to their most pressing formal interests at the time. But even if the Germans had just been looking at pictures and dismissed the critical texts, as Crockett suggests, what they would have surely noticed was how Carrà and de Chirico were overtly focused on two issues central to Dada and Constructivism: first, the question of hierarchy among objects and of objecthood itself; and, second, the issue of construction and the procedural choices inherent in the practice of assembling.

Therefore, what is striking is not that the Dadaists made a connection between Pittura Metafisica and Constructivism at the time, but rather that this connection has been forcibly removed by contemporary art historians who have seemingly felt compelled to read it as puzzling and “contradictory.” In reality, and this is what I hope to demonstrate in this essay, the Dadaists’ embrace of the Metaphysical Painters’ style owed more to a complex interplay of references to Expressionism, machine art, and – to a certain extent – Futurism that characterizes the early reception of de Chirico and Carrà.

Indeed, Futurism is the unacknowledged fourth interlocutor in this inter-artistic conversation between Germany, Russia, and Italy. Between 1918 and 1919, both German art critics and German Dadaists were looking for a conceptual reference that would allow them to move forward and away from the premises of Expressionism and pure abstraction. They found it in a renewed interest in Futurism’s bruitism and in Umberto Boccioni’s theorization of the use of a plurality of materials in sculpture.16

The question had been codified in Germany already before the war. In 1913, the critic Alfred Döblin, formerly a staunch supporter of Italian Futurism, had attacked Marinetti’s theory of words in freedom in an article remarkably titled “Ecce Müll” (“Ecce Rubbish,” a play of words based on Ecce Homo, or the figurative tradition of portraying the tortured body of Christ during the Passion). Döblin rejected the Futurists’ theorization of using “brute” matter, which removed any underpinning psychological order, and thus any guarantee of a hierarchical system of meaning within the work. The debate soon extended to Cubist collage; Futurist assemblages of real materials, first defined by Boccioni in his 1912 manifesto on Futurist sculpture;17 and Luigi Russolo’s theorization of the use of noise in music.18 This controversy led to a fundamental reorganization of the theoretical standpoints of German Expressionism. German art critics throughout the 1910s saw Futurism’s chaotic materialism as one of the elements that Expressionism had to resolve. In the words of Paul Fechter:

[For the Futurists,] the distance between human experience and its form must be reduced to a minimum, so the artistic form in itself will be felt as an obstacle. […] The Futurists position themselves in open contrast with the abstraction of Cubism, since they shift their attention [away from the value of composition] and toward the instinctive and the immediate. They attempt to represent the metropolis: the disorder and confusion generated by [its] multiplicity offer automatically, through the image of chaos, [what for them is] a meaningful image.19

The debate on this particular legacy of Futurism – intended as the representation of materiality and chaos – permeated not only the visual arts, but also the entire German academic and intellectual milieu. In his 1916 speech “Die Krisis der Kultur” (The Crisis of Culture), the influential German sociologist Georg Simmel referred explicitly to Futurism when explaining the impasse of contemporary culture, which was now only capable, in his words, of producing “a mere chaos of atomized formal elements.”20

After the war, the Futurists’ chaotic materialism became for a new generation of artists – including the Dadaists – an alternative model to Expressionism. It could attract the viewer’s attention on a visual and compositional level in much the same way as pure abstraction. But, as opposed to the Expressionists’ abstraction, the brute materialism theorized by the Futurists could also reinstate a connection with the real world by integrating reality itself, with all its psychological and emotional ramifications, into the composition.

Raul Hausmann defined this exact process in his manifesto “Das Neue Material in der Malerei” (The New Material in Painting) that he read at the first official Dada soirée in Germany, on April 12, 1918 (published later that year as “Synthetisches Cino der Malerei” [Synthetic Cinema of Painting]). Hausmann declared:

Cubist Orphism and Futurism, which were able to create a true interpenetration of their [material] means (colors on the canvas, cardboard, artificial hair, paper), were later limited by their own scientific, objective concerns. L’art dada will bring you a truly refreshing innovation, an impulse toward the true experience of a plurality of relationships. […] In Dada you will be able to recognize your truest condition: wonderful constellations made of real materials: wire, glass, cardboard, cloth – which correspond organically to your personal fragility and inconsistency.21

Hausmann repeatedly used the word “true” to suggest a direct connection between Dada’s materiality and the human experience created for the spectator. However, if we compare the materials that Hausmann identified as proper to Cubism and Futurism with those promoted by this new Dada art, we find something interesting. Among the many materials listed in the first group, only “artificial hair” can be characterized as moving beyond the bidimensionality of Cubist collage. It is a reference taken straight from Boccioni’s 1912 manifesto of Futurist sculpture, and it refers, more specifically, to the fact that Boccioni had famously inserted a real wig into one of his sculptural assemblages exhibited in Paris in 1913. But if we read an early typescript of the text, we find that Hausmann had originally included “Holz,” or wood – another material cited and used by Boccioni.22 Even more significantly, Boccioni had already theorized and employed every single one of the materials that Hausmann defined as proper to the new form of art dada: wire, glass, cardboard, and cloth.23 Several of these, on the other hand, still had to find their way into a real Dadaist painting.

Following Hausmann’s suggestions, in an apparent attempt to fill this problematic gap, in the summer of 1919 Kurt Schwitters presented his new Merz art at the Der Sturm gallery in Berlin as follows:

Merz art paintings are abstract works of art. Merz means, essentially, the montage of all possible materials for an artistic goal and, technically, the principle of indifference of individual materials. […] It is inessential whether all materials used had already been formed for some goal or not. The pram’s wheel, the metal net, the twine, and the cotton are elements that have the same right to be on the canvas as the colors. The artist intervenes by choosing, distributing, and configuring the materials within the artwork.24

Schwitters reframed the question of composition, which had been a major issue of contention in the theoretical debates over Expressionism and Futurism, in light of the contemporaneous calls for a return to materiality. It is not by chance, therefore, that Schwitters’s art was interpreted at the time as a merger between Expressionism and Hausmann’s Dadaism. Not everyone welcomed Schwitter’s idea. On the one hand, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler dismissed it as a mere return to Cubist collage and Futurist multimaterial sculpture; on the other, the Dadaist Walter Mehring saw in Schwitters the permanence of a sort of generic Expressionism, based on the fact that he used real objects not for themselves, but to revive that “Romantic old junk” that is the “sensual impulse of matter.”25

As the passage cited above indicates, however, Schwitters’s idea of the “Romantic old junk” of matter resulted from another intellectual interest he shared with Hausmann: the principle of “creative indifference” as theorized in 1918 by the philosopher, critic, and contributor to Der Sturm Salomo Friedlaender.26 According to Friedlaender, knowledge is often stifled by the human mind’s tendency to view the world through binary categories; still, it is possible to regain a viewpoint that allows us to consider a middle ground in which polar opposites are actually not opposed, but instead share a common set of features. This midpoint, or point of “indifference,” is exactly what allows for new, disruptive, and “creative” understandings of the world. Schwitters, like Boccioni before him, erased the traditional distance between real objects and artistic mediums, allowing for any of these elements (objects, paint, non-artistic materials) to be freely added onto the canvas. In a 1914 debate with Giovanni Papini, Boccioni had already suggested that this process would substantially reinstate the centrality of the artist’s subjectivity, and not (as critics feared) drown art in the chaos of matter.27

As Schwitters pointed out in his text, the artist’s role was to select and configure the various elements within the picture. This return to the process of composition as a central, organizational, intellectual task demonstrated a form of control which he felt was needed to counter the Expressionists’ emotional, and substantially irrational, disengagement from the question of composition. Schwitters’s idea of a montage of real materials that would imply some kind of subjective control was the backdrop against which several new artistic trends were starting to be welcomed and understood in Germany. We can therefore see why, in 1920, critics quickly linked Tatlin’s art to Schwitters’s exhibition from the year before. But this convergence of experiments in montage had even more unexpected consequences.

In the issue of Der Ararat featuring Umanski’s article on Tatlin, the critic and gallery owner Leopold Zahn published an essay introducing the Valori Plastici group to the German public. Here is a passage from Zahn’s article:

A strange, motionless world – almost sinisterly motionless – takes form. […] Things are not there because of some sort of love for their material existence, but instead as mathematical symbols and geometric laws. […] [The idea of] man as a vital organism is banned from this crystalline world. He has the right to enter it only as a mannequin, the proof of the mechanical functioning of the human body.28

Zahn’s account of Pittura Metafisica and Umanski’s reading of Tatlin’s art do not simply appear in the same issue of the journal. They are also conceptually linked in a note by the journal’s editorial board, published as a coda to Umanski’s article:

This Art of the Machine has already had its first introduction in Germany through the Merzbildern exhibition, which was recently held at the Der Sturm gallery. Daniel-Henry [Kahnweiler] has reminded us in the November issue of Das Kunstblatt – and with reason – that Picasso and Braque already started this artistic tendency in Paris in 1913. The Italian Futurists and members of the Dada group followed the example of the Cubists. These intentions, underlying all attempts of this kind, also play a role in the metaphysical inclinations found in the new Italian art (see above).29

At the very beginning of 1920, Tatlin and his new “art of the machine” are therefore described as inherently connected to the new Italian Metaphysical art. This is not a mere quip on the part of the journal. What Zahn and Der Ararat found attractive in the Valori Plastici group is exactly its overtly staged internal organization. For Zahn, this exhibited, inner construction of the elements in the painting could signify a new return to rationality and order.

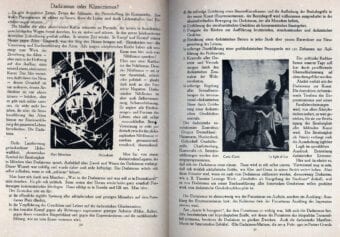

Soon after the publication of these two essays, in April 1920 Der Ararat summarized the state of art by way of a striking visual alternative. Under the slogan “Dadaism or Classicism?,” it published reproductions of two artworks on subsequent pages: a woodcut by Schwitters followed by Carrà’s painting Le figlie di Lot (The Daughters of Lot, 1919; figure 3). The article, written again by Zahn, is structured as an attack against Dadaism as a radical, destructive force, and it is framed by two rhetorical questions: “Self-irony or self-evolution?” and “Demolition or destruction?” Interestingly, to bolster his interpretation, Zahn referred to Italian Futurism and set up a parallel between the German and Italian movements: “Dadaism is not a prelude, but a conclusion, just like Futurism was a conclusion: it’s the end of Expressionism, or Cubism (just like Futurism was the end of Impressionism).”30 If German Dada had embraced the Italian Futurists’ use of raw reality (noise, matter, found objects) to counter the Expressionists’ spiritualization of art, Zahn here reunited them in one single indictment: “All the bruitist and scatological witty remarks that the Futurists used to irritate the bourgeoisie’s eardrums, the Dadaists use them with the same goal.”31 For Zahn, Italian and German identities run parallel and one offers responses to the problems of the other. Binding Dadaism and Futurism together, he proposed a return to figuration as an anti-avant-garde, or better, a post-avant-garde move, for which the icon of the “converted Futurist” Carlo Carrà provided a convincing justification.

We are familiar with the idea that Pittura Metafisica constituted a major figural and theoretical reference for the retour à l’ordre tendency of the 1920s. What I would like to highlight in the rest of this essay are some lesser-known interpretations that directly countered this narrative at the time. In order to do so, we must go back to that very successful definition of Tatlin’s art as “of the machine,” and to the way in which machine art was seen as a form of extreme realism coupled with a long-awaited detachment from Expressionist spiritualism. Already in 1918, in a letter to Hannah Höch, Hausmann had written: “You don’t regard my new artistic efforts as a way of distancing myself from Expressionism. […] The Dadaist […] will not translate something which today has a specifically mechanical character, like typography, or its dynamic form, like the Dadaist kind of typography, into another material. It is exactly the mechanical element that we need to highlight.”32

Now, confronted by the art of the Valori Plastici group, during 1919–20, Hausmann codified the confluence of Futurism, Dada, and Pittura Metafisica under the new, overarching category of “art of the machine.” He did not renounce, however, his previous theorization of materiality, but moved onward from it. De Chirico’s and Carrà’s treatment of space became, for him, a functional tool to merge extreme realism with the return of the principle of composition: an attempt to create a visual container that reunites the innumerable and contradictory elements of modern life. For the Dadaists, as opposed to Zahn, the environments created in de Chirico’s and Carrà’s works were not the result of a new classicism, intended as an alternative to chaos; they were, instead, functional visual machines that allowed for more effective representations of the real, contemporary chaos of the machine age.

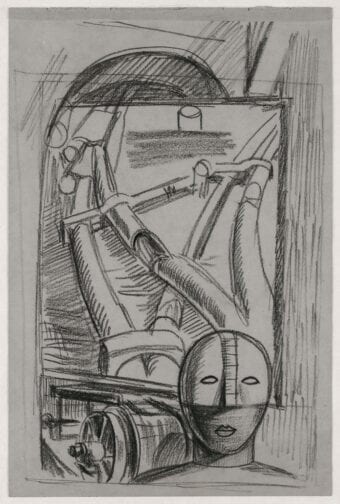

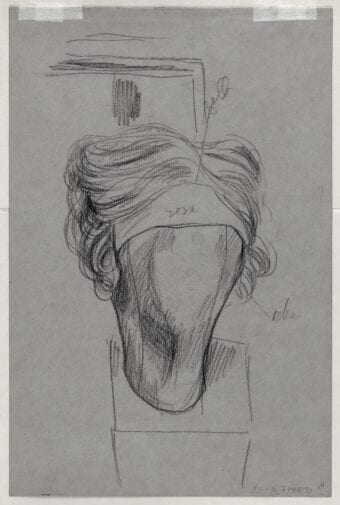

A double-sided drawing by Hausmann, Vorstudie zu ‘Mechanischer Kopf’ (Preliminary study for the Mechanical Head, c. 1920; figures 4 and 5)33 clarifies his attempt to visually translate his theories at this time. On the recto, we see an industrial setting with an intricate network of pipes converging toward a turbine. In the foreground there is a semi-mechanical figure with a mask on the upper part of the face – probably a factory worker or engineer, a recurring theme in the later work of the Italian Futurists. The verso shows a more explicitly Chirico-esque subject: a wooden mannequin head with a wig. Indeed, its wigged head is very similar to that portrayed by Carrà in his painting La camera incantata (The Enchanted Chamber, 1917).34 It is quite possible that Hausmann saw it, since it was reproduced in the same issue of Valori Plastici in which Daübler published the first part of his essay “Nostro retaggio” (Our Legacy, 1919).35 These two sketches summarize the two elements that Hausmann was trying to reunite during these months. They will finally merge in his famous assemblage Der Geist Unserer Zeit – Mechanischer Kopf (The Spirit of Our Time – Mechanical Head, c. 1920; figure 6), which was exhibited that summer at the International Dada Fair. Scholars have failed to notice that all the drawings and sketches that could be linked to this famous work are in reality the result of Hausmann’s obsessive analysis of the Metaphysical theme of the mannequin head, to which he returned over and over again that year.

Two pencil portraits that he made of the artist Conrad Felixmüller,36 for example, show a head mounted on a square base, lying on a table, in an interior. The first version is drawn in a pure Metafisica style: we notice the perspectival slats of the wooden floor; an upholstered chair on the left, in front of a closed door; and a window on the right. The top of an easel is barely visible behind Felixmüller’s head. The second version shows a Dadaist transmutation of the first: the setting is exactly the same, but some details have changed. The door is now on the right and behind the chair we see the painting of a man that is quite similar in style to Grosz’s and Dix’s works of the time; another drawing hangs at the very back of the room. The Metafisica interior is slowly transforming into one of the showrooms of that year’s Dada Fair. Felixmüller’s face is covered with writing, indicating his identity and how the image should be colored, as in a paint-by-number diagram: “Felixmüller,” “A1,” “rot” (red). His hairline marks an opening on the back part of the skull, showing his brain. Finally, his forehead is covered with a measuring line, located where Hausmann will later glue the seamstress’s tape measure onto the mechanical head of Der Geist Unserer Zeit – Mechanischer Kopf.

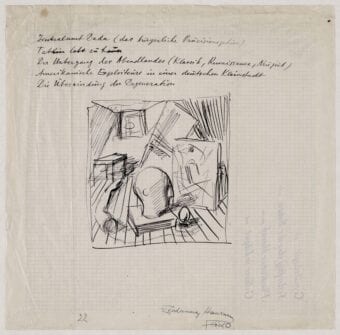

A lesser-known ink sketch created before the two Felixmüller drawings, Sketch II (1920; figure 7), reveals that Hausmann had originally conceived the subject in a manner much more reminiscent of de Chirico’s works: the head is here abandoned on the wooden floor, still mounted on its square pedestal. On the left, a puppet’s arm (maybe another excerpt of Felixmüller’s dismembered body) stretches backward. On the right, we see a large painting with an arch, matching the style of de Chirico’s urban landscapes. The progression of these works (first the two pencil sketches; the ink sketch; the two drawings of Felixmüller’s head; and finally, the sculpture) clarifies how the model of Pittura Metafisica functioned as an operational layout upon which Hausmann progressively added a series of Dadaist specifications. His handwritten notes on top of the ink drawing further link it to the series of Chirico-esque collages that he went on to exhibit at the Dada Fair that summer, and connect this series of drawings to his participation in that show.37

Hausmann’s theoretical ruminations went along with his visual experiments. In February 1920, in an essay titled “Kabarett Zum Menschen” (Cabaret for the People), he introduced for the first time in his writings the marionette as a symbolic operator of the new mechanical sensibility, clarifying: “The human consciousness consists merely of insignificant accessories that have been stuck to its surface.”38 In the second half of the year, he reconfigured the relationship between painting and photography in light of the use of new objects that he had just achieved with Der Geist Unserer Zeit – Mechanischer Kopf and the experiments in mixing watercolor and photographic collage that he exhibited at the Dada Fair. In a manuscript titled “Gesetze der Malerei” (Laws of Painting), dated September 1920 (it was co-signed by Georg Grosz, John Heartfield, and Rudold Schlichter, but never published), Hausmann put the art of Carrà and de Chirico in direct relationship with his own recent effort to move away from the dissolution of painting, caused by Rembrandt and the Expressionists, and to incorporate reality by means of photography. The manuscript reads:

In Europe, painting begins anew with Ingres; it found its final development with Carrà and de Chirico. Painting is the representation of material space through the relationship of the bodies. The concept of the bodies was identified through stereometry and perspective, which allowed us to have a clear conception of vision and of the optical milieu for the first time. Materialistic painting is based on the plasticity and the solidity of perception, and not on the uncertainty of subjective impressions or spiritual digressions. If we are compelled to accept a metaphysics, it should be grounded in matter itself and should not be represented as separated from it. […] Perspective is the rule and [inner element of] control of painting. […] We need to be capable builders in order to construct machines and buildings. [But] for a closer analysis of details we do not disdain the use of photography. [After] the predilection for the arbitrariness and formlessness of the Expressionists, in our time, we advocate a clear and definite materialistic painting.39

Hausmann’s new reconfiguration of materialism culminated, therefore, in the integration of the real object already transformed into an image through the use of photography. The photographic object thus became a tautological surrogate of reality itself. It is interesting to note, however, that by this time Hausmann was still referring to the need to draw and paint a virtual setting for these photographic scraps of reality, as he had done in the works exhibited at the Dada Fair, such as Tatlin lebt zu Hause. Carrà’s and de Chirico’s environments are the perfect choice for this goal: they provide a stage set environment that not only is overtly artificial, but displays its own artificiality as a distinctive feature of the artwork itself. The rudimentary, imperfect use of one-point perspective is what immediately betrays the presence of an artist in these compositions: this is why Pittura Metafisica seems to move one step backward from the Renaissance’s ambition of a perfect three-dimensional illusionism. De Chirico’s calls for a return to craftsmanship notwithstanding, the spatial imperfection in his and Carrà’s works constitutes visual proof of their human foundation, of the artist’s intervention in the definition of space. It is what Mario Bacchelli called, in Valori Plastici, regaining the “concept” – as opposed to the rules – of perspective.40 Because of their exhibited artificiality, moreover, these Metafisica interiors can easily be interpreted as metaphors of the human mind: containers of loosely related (or unrelated) visual experiences, of conflicting or discarded memories, that have not yet found their hierarchical structure of classification. The mysterious principle of association among Pittura Metafisica’s objects – a principle that is not a-hierarchical as much as pre-hierarchical – offers a compelling visualization of the idea of “creative indifference” that is so central to the Dadaists at this time.41

Ultimately, it was this exhibited artificiality, mixed with the psychological projection of a hierarchical indifference, that attracted the Dadaists. Since, for Hausmann, “perspective is the inner rule and element of control of the painting,” the construction of a perspectival space is the operation that most clearly links the artist’s identity with that of the constructor: the new artist-engineer personified by Tatlin. This is the fundamental meaning of a work such as Tatlin lebt zu Hause, which reunites the chaos of the modern industrial world in a Pittura Metafisica interior. Tatlin’s home is also a three-dimensional projection of the contents of Tatlin’s head, his obsession with modern life and its technological objects. The Russian artist is rendered through the photograph of an unnamed, modern-dressed man (Hausmann later stated that he had cut it out from an American magazine)42 on the forefront of the watercolor interior. Hausmann glued a second cut-out magazine illustration, of a steering wheel, onto the upper part of the man’s head, suggesting that his brain is completely filled with machinery. Similarly, Dada Siegt!, alternatively titled A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement, represents the three-dimensional projection of the contents of somebody’s mind: the collage of a head with an exposed brain is surrounded by an array of scientific and technological products.

As mentioned earlier in this essay, in the fall of 1920, Höch traveled to Italy. In her diary, we find the addresses of Enrico Prampolini and Italo Tavolato. At that time, Prampolini was busy launching the highly politicized Roman exhibition of the Novembergruppe in his gallery.43 Höch arrived in Rome too late to visit the show, which opened on October 23 with a lecture by Marinetti and included two works by Dix and two by Schwitters. Still, she obtained a copy of the gallery’s bulletin, and wrote in it a reference to Corrado Govoni’s 1915 Futurist book of experimental typography, Rarefazioni, and the note “De Chirico.”44 She also acquired, directly from Prampolini, a copy of Marinetti’s “Manifesto of Futurism” in French.45 Höch jotted down the news she heard in the artistic circles in Rome (maybe from Prampolini himself); in particular, the accusations against Valori Plastici – seen as an overtly anti-avant-gardistic, reactionary endeavor – had a deep impact on her. An unpublished diary note reads: “2 Issues of BLEU in Mantova. Marinetti in Milano. Tzara from Constantinople through Naples to Paris. Severini in Paris? Carrà in Paris! De Chirico will become a professor at the Art Academy [Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor].”46 We do not know how seriously Höch took the quip that many at that time were muttering against de Chirico.47

She surely read the unflattering article on Dada that the journalist Telesio Interlandi had published in the October issue of Noi e il mondo.48 We can imagine her surprise when, having purchased a copy of the magazine at a newsstand in Rome, she saw that the article contained a half-page photo of herself with her Dadaist dolls. References to French and German Dada had become a recurring theme in the Italian press and the movement was paraded as the latest result of avant-garde nihilism and political radicalism. “Under this mask of madness hides a desire for anarchy. […] As it used to happen in Petersburg, so [it happens] in Berlin. In the slums,” Interlandi had written.49 These readings of Dada, in turn, had pushed the Valori Plastici group to take a clear stance against it, while also trying to combat the accusation of being a mere return to academicism. It is probable that while in Rome Höch also heard about the attack that Italo Tavolato had just launched against Dadaism in the May–June issue of Valori Plastici, associating it with a larger, anti-humanistic cultural trend brought about by mechanization.50 In the same issue, Carrà had linked Dadaism and academicism as “the two inverted sides of the same lie,” dismissing the idea of the artists’ direct involvement in politics: “It might be time to acknowledge that the fiercest ambitions were finally smashed by the historical reality upon which they wanted to work.”51 Carrà was talking here first and foremost about his own Futurist past and about those artists in the contemporary Italian scene who were trying to resurrect Futurism’s involvement in politics,52 but his new stance against the merger of art and political radicalism had an echo beyond the borders of Italy.

At the end of the year, probably due in part to the news brought back by Höch, the German Dadaists finally recognized their ideological distance from Valori Plastici. In the words of Grosz: “In an effort to develop a clear and simple style, one cannot help but draw closer to Carrà. Nevertheless, everything that in him wants to be metaphysical and bourgeois distances me from him.”53 Defending his use of a clearly readable style, Grosz also reinstated the centrality of the dehumanized, mechanical character of modern life: “I am trying in my so-called works of art to construct something with a completely realistic foundation. Man is no longer an individual to be examined in subtle psychological terms, but a collective, almost mechanical concept.”54

It is exactly this mechanical concept of humanity that another avant-garde artist in Holland was reconfiguring through the lens of Valori Plastici. Constructing a veritable Italian alter ego for himself, in 1921 Theo van Doesburg started publishing texts in his journal De Stijl under the pseudonym Aldo Camini. The most famous of these is titled “Caminoscopie. ‘n Antifilosofische levenbeschouwing zonder draad of systeem” (Caminoscopy: An Anti-Philosophical View of Life, With No Wires or System), supposedly the translation of a manuscript that van Doesburg had found in the studio of a “totally unknown” painter in Milan.55 Van Doesburg had studied Italian with the Florentine intellectual Romano Guarnieri, who had introduced him to the debates of the Florentine Futurists.56 While scholars have pointed out that van Doesburg modeled the figure of Camini after the Futurist journalist and literary critic Giovanni Papini, little attention has been paid to the fact that, with Camini, van Doesburg was actually attempting to correct the development of Italian modern art by also recuperating an early Carrà.57

The fictive philosopher Camini is the impossible projection of a Carrà who has returned to his Futurist roots and started feeling like a Futurist again. The mysterious C.C., author of the text, who is presented by van Doesburg as a recently deceased “Metafisica artist,” is none other than Carrà himself. The last section of the manuscript, as Craig Eliason has noted, stages a reinterpretation of the Ovale delle Apparizioni (Oval of Apparitions, 1918; figure 8) as the portrayal of a modern-day hero, the “radio-electric man.”58 The painting, along with Carrà’s accompanying essay “Il quadrante dello spirito” (The Quadrant of the Spirit), had been published in the first issue of Valori Plastici, in November 1918.59 Carrà’s new work must have seemed of capital importance to van Doesburg, since he immediately commissioned a Dutch translation of the essay, which was published only five months later, in the May 1919 issue of De Stijl, along with a reproduction of the painting.60

In the foreground of the Ovale is a mannequin constructed of colored wooden slats. Carrà was at the time strongly influenced by Alexander Archipenko’s assembled sculptures,61 and the figure in the Ovale merges the first version of Archipenko’s assemblage Médrano (1912–13, destroyed) and the multicolored plaster sculpture Carousel Pierrot (1913).62 In his essay for Valori Plastici, Carrà had interpreted the mannequin as an “electrical man” whose bust is built out of “mobile, circular planes made of multicolored tin that make us consider reality as seen through concave and convex mirrors.”63 The figure is surrounded by “the antenna of the Marconi-telegraph,” murmuring “legends” that recur every spring, while in the background “the metaphysical house of the Milanese proletarians encloses an immense silence.”64

In 1920, one year after celebrating Carrà’s work in De Stijl, van Doesburg published a note championing the Futurists’ manifesto “Contro tutti i ritorni in pittura” (Against All Returns in Painting) while taking his distance from “certain Futurists that imitate Giotto.”65

Given this overt recognition of Carrà’s position, it is difficult to understand why, starting in 1921, van Doesburg would return to him once again. The only possible answer is that he was crafting an alternative development of modern art that salvaged and reformulated Pittura Metafisica for the sake of the contemporary avant-garde. Van Doesburg’s “Caminoscopie” went beyond a simple retelling of Carrà’s Ovale delle Apparizioni, and constructed instead a carefully staged merger of Carrà’s 1918 essay “Il quadrante dello spirito” and Marinetti’s 1910 manifesto “L’Uomo Moltiplicato e il Regno della Macchina” (Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine). Enclosed by the “future, electrifying living atmosphere that surrounds him,” Camini’s humanoid figure has “radio electric conductors as limbs” that send waves into his surrounding space. The uncanny co-presence of disparate elements in Carrà’s composition are explicable as a reversion to the Futurist concept of simultaneity.66 Reflecting the dream of the German Dadaists, Camini’s radio-electric man lives in a world of “mechano-technical diagrams.” Even his body, with truncated limbs, is constructed of “plates of different metals, auto-mechanical, moving in all known and unknown dimensions of space.”67 Camini explained this in purely Marinetti-inspired terms: “I am convinced that the well-tended relics, which you call your limbs, are totally unusable for the future.”68 His conclusion is that “in the future both will permeate each other: man and machine will form an entirely new organo-mechanism.”69

Van Doesburg’s merger of technology and Pittura Metafisica in his reading of the Ovale delle Apparizioni as the reign of the radio-electric man derives from something that Carrà himself had originally put to use: the idea of a humanlike figure that flaunts its artificial, constructed nature rather than concealing it – something that Carrà had found in the sculptures of Archipenko. This centrality of the principle of constructing, assembling, and reuniting disparate elements into a new form of reality that eludes any naturalism is the fil rouge that, for a couple of years, brought together de Chirico, Carrà, Tatlin, van Doesburg, and the German Dadaists. While the idea of a possible avant-garde kinship among them would soon fade, the interplay of construction, composition, and artificiality would remain paramount to the European avant-garde in the decade to follow. From a standpoint quite similar to that of Camini, a new generation would rework the boundaries of Constructivism and machine art, pushing the issue of mechanical identity into an analysis of the limits of human activity and ideology.70

Bibliography

Bacchelli, Mario. “Note.” Valori Plastici 2, nos. 3–4 (March–April 1920): 39.

Bacchelli, Mario. “Note (Marzo–Aprile 1920): Accademia.” Valori Plastici 2, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1920): 63.

Baljeu, Joost. Theo van Doesburg. New York: Macmillan, 1974.

Benson, Timothy O. “Dada Geographies.” In Virgin Microbe: Essays on Dada, edited by David Hopkins and Michael White, 25–39. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2014.

Benson, Timothy O. “Mysticism, Materialism, and the Machine in Berlin Dada.” Art Journal 46, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 46–55.

Benson, Timothy O. Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1987.

Bergius, Hanne. “Dada Triumphs!” Dada Berlin, 1917–1923 Artistry of Polarities. Montages – Metamechanics – Manifestations. Farmington Hills, MI: G. K. Hall, 2003.

Boccioni, Umberto. “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture” (1912). In Futurist Painting Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism), edited by Maria Elena Versari, translated by Richard Shane Agin and Versari (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2016).

Bollettino quindicinale della Casa d’Arte Italiana, no. 1 (October 15, 1920).

Bressan, Marina. “Theodor Däubler: A Mediator between Florentine Futurism and German Modernism.” International Yearbook of Futurism Studies 4 (2014): 450–76.

Cardoff, Peter. Freidlaender/Mynona Zur Einfüring. Hamburg: Edition Soak im Junius Verlag, 1988.

Carrà, Carlo. “De Wijzerplast Van Den Geest.” Translated by Mary Robbers. De Stijl 2, no. 7 (May 1919): 75–77.

Carrà, Carlo. “Il quadrante dello spirit.” Valori Plastici 1, no. 1 (November 15, 1918): 1–2.

Carrà, Carlo. “Il rinnovamento della pittura italiana (parte IV).” Valori Plastici 2, no. 5–6 (May–June 1920): 53–55.

Crockett, Dennis. German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder, 1918–1924. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1999.

Daübler, Theodor. “Nostro retaggio.” Valori Plastici 1, nos. 6–10 (June–October 1919): 1–5.

Del Puppo, Alessandro. “Lacerba” 1913–1915. Arte e critica d’arte. Bergamo: Lubrina Editore, 2000.

Eliason, Craig. The Dialectic of Dada and Constructivism: Theo van Doesburg and the Dadaists, 1920–1930. PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2002.

Eliason, Craig. “Theo van Doesburg: Italian Futurist?” In The Low Countries: Crossroads of Cultures, edited by Thomas F. Shannon, Ton J. Broos, and Margriet Bruyn Lacy, 47–56. Münster: Nodus, 2006.

Elder, R. Bruce. Dada, Surrealism and the Cinematic Effect. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013.

Frambach, Ludwig. “The Weighty World of Nothingness: Salomo Friedlaender’s Creative Indifference.” In Creative License: The Art of Gestalt Therapy, edited by Margherita Spagnuolo Lobb and Nancy Amendt-Lyon, 113–28. Vienna: Springer, 2003.

Freidlaender, Salomo. Shöpferische Indifferenz. Munich: Müller, 1918.

Grosz, George. An Autobiography. New York: MacMillan, 1983.

Grosz, George. “Zu meinen neuen Bildern” (November 1920). Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 1 (January 1921): 14.

Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, vol. 2, 1919–1920. Edited by Cornelia Thater-Schultz. Berlin: Argon/Berlinische Galerie, 1989.

Hausmann, Raoul. Am Anfang war Dada. Edited by Karl Riha und Günter Kämpf. Steinbach: Anabas, 1972.

Hausmann, Raoul. Letter to Hannah Höch, June 5, 1918, Berlin. Berlinische Galerie website https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=207276&viewType=detailView.

Hausmann, Raoul. “Technische Bemerkung zur Kunst” (Technical Notes on Art, June 17, 1918). Nachlass Hannah Höch. Berlinische Galerie website, https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=215236&viewType=detailView.

Höch, Hannah. Tagebucher, 1920. Hannah Höch Archiv, Berlinische Galerie.

Interlandi, Telesio. “Dadà.” Noi e il mondo. Rivista mensile della Tribuna, no. 10 (October 1, 1920).

Kurt Schwitters. Das Literarische Werk, V. Manifeste und kritische Prosa. Edited by Friedhem Lach. Cologne: Du Mont, 1981.

Lepik, Andres. “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico tra Italia e Germania.” In Valori Plastici. Milan: Skira, 1998. Exhibition Catalogue.

Lewis, Beth Irwin. George Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic. PhD diss., University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1969.

Lista, Giovanni. “Van Doesburg et les futurists.” In Theo van Doesburg, edited by Serge Lemoine, 150–57. Paris: Sers, 1990.

MacBride, Patrizia. “Cut with the Kitchen Knife: Visualizing Politics in Berlin Dada.” In Art and Resistance in Germany, edited by Deborah Asher Barnstone and Elizabeth Otto, 35–36. London: Bloomsbury 2019.

Mehring, Walter. “Ausstellungen: Berliner Ausstellungen – Kurt Schwitters im ‘Sturm.’” Der Cicerone 11, no. 14 (1919): 462.

Miesel, Victor H., ed. Voices of German Expressionism. New York: Harry N. Abrams and Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Off, Heinz. Hannah Höch. Berlin: Mann, 1968.

Poggi, Christine. In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992.

Presilla, Lucia. “Alcune note sulle mostre di Valori Plastici in Germania.” Commentari d’arte. Rivista di critica e storia dell’arte 5, no. 12 (January–April 1999): 51–67.

Simmel, Georg. Der Krieg und die geistigen Entscheidungen. Reden und Aufsätze. Munich and Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1917.

Thiel, Detlef. Experiment Mensch. Freidlaender/Mynona Brevier. Herrshing: Watawhile, 2014.

Tujiin, Marguerite. Mon cher ami … Lieber Does … Theo van Doesburg en de praktijk van de internationaleavant-garde. Een beschouwing over de avant-garde in de jaren 1916–1930, gevolgd door eenbecommentarieerde uitgave van de correspondentie tussen Van Doesburg en Alexander Archipenko, Tristan Tzara, Hans Richter en Enrico Prampolini. PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2003, https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.209367.

Sheppard, Richard. Modernism Dada Postmodernism. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2000.

Tavolato, Italo. “La maschera della meccanica.” Valori Plastici 2, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1920): 49–52.

Umanski, Konstantin. Neue Kunst in Russland. 1914–1919. Potsdam: Kiepenheuer; Munich: Goltz, 1920.

Umanski, Konstantin. “Russland: Neue Richtungen in Russland: I. Der Tatlinismus oder die Maschinenkunst.” Der Ararat 1, no. 4 (January 1920): 12–13.

Van Doesburg, Theo. “Caminoscopie: ’n Antifilosofische levenbeschouwing zonder draad of systeem” (Caminoscopy: An Anti-Philosophical View of Life, With No Wires or System). De Stijl, vol. 4, no. 5 (June 1921): 65–71; no. 6 (June 1921): 82–89; no. 8 (August 1921): 118–22; vol. 5, no. 6 (June 1922): 86–88; vol. 6, nos. 3–4 (May–June 1923): 33–37, and nos.6–7 (1924): 74–78.

Van Doesburg, Theo. “Rondblik.” De Stijl 3, no. 9 (July 1920): 80.

Versari, Maria Elena. “Futurist Canons and the Development of Avant-Garde Historiography (Futurism – Expressionism – Dada).” In Back to the Futurists, edited by Elza Adamowicz and Simona Storchi, 72–94. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013.

Versari, Maria Elena. “Futurist Machine Art, Constructivism and the Modernity of Mechanization.” In Futurism and the Technological Imagination, edited by Günter Berghaus, 149–76. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009.

Versari, Maria Elena. “I rapporti internazionali del Futurismo dopo il 1919.” In Il Futurismo nelle Avanguardie. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Milano del 4–6 febbraio 2010, Palazzo Reale, Sala delle Otto Colonne, edited by Walter Pedullà, 577–606. Rome: Edizioni Ponte Sisto, 2010.

Versari, Maria Elena. “The Style and Status of the Modern Artist: Archipenko in the Eyes of the Italian Futurists.” In Alexander Archipenko Revisited: An international perspective, Proceedings from the Archipenko Symposium, Cooper Union, New York City, September 17, 2005, 18–22. New York: The Archipenko Foundation, 2008.

White, Michael. “Van Doesburg: A Counter-life.” In Constructing a New World: Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing 2009.

[Zahn, Leo]. “Anmerkung der Redaktion.” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 13.

Zahn, Leo. “Dadaismus oder Klassizismus?” Der Ararat, no. 7 (April 1920): 50–52.

Zahn, Leo. “Italien: Die metaphysische Malerei.” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 8.

How to cite

Maria Elena Versari, “Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor”: Expectations, Misunderstandings, and Appropriations of Pittura Metafisica Among the 1920s European Avant-Garde,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- I would like to thank Timothy Benson for his help with my research over the years, and for the invaluable suggestions he offered for this article. I would also like to thank John J. Heartfield, Stefan Ståhle (Moderna Museet); Anne-Catherine Biedermann (RMNGP, Paris); and Christian Tagger (Berlinische Galerie).

- Konstantin Umanski, “Russland. Neue Richtungen in Russland. I. Der Tatlinismus oder die Maschinenkunst,” Der Ararat 1, no. 4 (January 1920): 12. See also Umanski’s monograph of the same year: Neue Kunst in Russland. 1914–1919 (Potsdam: Kiepenheuer; Munich: Goltz, 1920). Unless otherwise noted, all translations are mine.

- Timothy O. Benson, “Mysticism, Materialism, and the Machine in Berlin Dada,” Art Journal 46, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 46.

- Raoul Hausmann, Dada siegt! (1920), watercolor and collage mounted on board, private collection.

- Hanne Bergius, “Dada Triumphs!”: Dada Berlin, 1917–1923, Artistry of Polarities: Montages – Metamechanics – Manifestations (Farmington Hills, MI: G. K. Hall, 2003), 194.

- Ibid., 194.

- Dennis Crockett, German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder, 1918–1924 (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1999), 49.

- Ibid., 19.

- See Heinz Off, Hannah Höch (Berlin: Mann, 1968), 17; and Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, ed. Cornelia Thater-Schultz, vol. 2, 1919–1920 (Berlin: Argon/Berlinische Galerie, 1989), 637–38 and 726. Hausmann dedicated the book to Höch “in memory of her Italian trip 1920.”

- Marina Bressan, “Theodor Däubler: A Mediator between Florentine Futurism and German Modernism,” International Yearbook of Futurism Studies 4 (2014): 450–76.

- Andres Lepik, “Un nuovo Rinascimento per l’arte italiana? ‘Valori Plastici’ e il dialogo artistico tra Italia e Germania,” in Valori Plastici (Milan: Skira, 1998), 155–64; and Lucia Presilla, “Alcune note sulle mostre di Valori Plastici in Germania,” in Commentari d’arte. Rivista di critica e storia dell’arte 5, no. 12 (January–April 1999): 51–67.

- George Grosz, An Autobiography (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1983), 100. See also Beth Irwin Lewis, George Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1969), 271.

- Ibid., 101.

- Hannah Höch, Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (1919), collage of pasted papers, Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

- Patrizia MacBride, “Cut with the Kitchen Knife: Visualizing Politics in Berlin Dada,” in Art and Resistance in Germany, ed. Deborah Asher Barnstone and Elizabeth Otto (London: Bloomsbury 2019), 35–36.

- See Maria Elena Versari, “Futurist Canons and the Development of Avant-Garde Historiography (Futurism – Expressionism – Dada),” in Back to the Futurists, ed. Elza Adamowicz and Simona Storchi (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), 72–94.

- See Umberto Boccioni, “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture” (1912), in Futurist Painting Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism), ed. Maria Elena Versari, trans. Richard Shane Agin and Maria Elena Versari (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2016).

- For a reassessment of the debate, see Versari, “Futurist Canons and the Development of Avant-Garde Historiography (Futurism – Expressionism – Dada).”

- Paul Fechter, quoted in ibid., 80.

- “Nur ein Chaos atomisierter Formstücke.” Georg Simmel, “Die Krisis der Kultur,” in Der Krieg und die geistigen Entscheidungen. Reden und Aufsätze (Munich and Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1917), 51. The essay was read publicly in Vienna in January 1916 and published the following year in an anthology of Simmel’s texts on contemporary culture; see the online edition of Simmel’s works edited by Hans Geser at http://socio.ch/sim/krieg/krieg_kris.htm. On Simmel’s interpretation of Futurism, see Versari, “Futurist Canons,” 83–84.

- Raoul Hausmann, “Synthetisches Cino der Malerei” (1918), in Am Anfang war Dada, ed. Karl Riha und Günter Kämpf (Steinbach: Anabas, 1972), 28–29. See also Timothy O. Benson, Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1987), 80.

- Raul Hausmann, “Technische Bemerkung zur Kunst” (Technical Notes on Art), typescript dated June 17, 1918, Nachlass Hannah Höch, Berlinische Galerie, online at: https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=215236&viewType=detailView.

- “Thus transparent planes, glass, sheets of metal, wires, external or internal electric lights will be able to indicate the planes, tendencies, tones, and semitones of a new reality. […] We must declare that even twenty different materials can come together in a single work for the sake of the plastic emotion. Here are a few of them: glass, wood, cardboard, iron, cement, horsehair, leather, cloth, mirrors, electric lights, etc.” Boccioni, “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture,” 182–83.

- Kurt Schwitters, “Die Merzmalerei,” in Kurt Schwitters. Das Literarische Werk, V. Manifeste und kritische Prosa, ed. Friedhem Lach (Cologne: Du Mont, 1981), 37. Originally published in Der Sturm 10, no. 4 (July 4, 1919): 61.

- Walter Mehring, “Ausstellungen. Berliner Ausstellungen – Kurt Schwitters im “Sturm,” Der Cicerone 11, no. 14 (1919): 462.

- See Timothy O. Benson, “Dada Geographies,” in Virgin Microbe: Essays on Dada, ed. David Hopkins and Michael White (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2014), 25–39. See also Salomo Freidlaender, Shöpferische Indifferenz (Munich: Müller, 1918); Peter Cardoff, Freidlaender/Mynona Zur Einfüring (Hamburg: Edition Soak); Detlef Thiel, Experiment Mensch. Freidlaender/Mynona Brevier (Herrshing: Watawhile, 2014); R. Bruce Elder, Dada, Surrealism and the Cinematic Effect (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013), 99–100; and Ludwig Frambach, “The Weighty World of Nothingness: Salomo Friedlaender’s Creative Indifference,” in Creative License: The Art of Gestalt Therapy, ed. Margherita Spagnuolo Lobb and Nancy Amendt-Lyon (Vienna: Springer, 2003), 113–28.

- See Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 164–93; and Alessandro del Puppo, “La polemica tra Papini e Boccioni,” in “Lacerba” 1913–1915. Arte e critica d’arte (Bergamo: Lubrina Editore, 2000), 187–208.

- Leo Zahn, “Italien. Die metaphysische Malerei,” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 8.

- “Anmerkung der Redaktion,” Der Ararat, no. 4 (January 1920): 13.

- Leo Zahn, “Dadaismus oder Klassizismus?,” Der Ararat, no. 7 (April 1920): 51.

- Ibid.

- Letter from Raoul Hausmann to Hannah Höch, June 5, 1918, Berlinische Galerie, https://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=207276&viewType=detailView. Cited from the English translation (with slight variations) in Benson, Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada, 88.

- Both drawings are published in the online collection of the Berlinische Galerie, https://sammlungonline.berlinischegalerie.de:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=17875&viewType=detailView.

- Carlo Carrà, La camera incantata (1917), oil on canvas, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

- Theodor Daübler, “Nostro retaggio,” Valori Plastici 1, nos. 6–10 (June–October 1919): 1–5.

- Portrait of Conrad Felixmüller (1920), pencil on paper, Centre Pompidou-Musée national d’art moderne, Paris; and Portrait of Conrad Felixmüller as a Mechanical Head (1920), pencil on paper, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

- The note mentions “Zentralamt Dada (das bürgerliche Präcisionsgehirn),” which is the complete title of the collage better known as Dada siegt! that Hausmann exhibited that year at the Dada Fair, along with another work whose title is reported in the note: “Tatlin lebt zu Hause.” The other three lines of text are probably other possible titles for works that Hausmann planned to create for the Dada Fair. Translated, they read: “The Decline of the West (Classic, Renaissance, Contemporary),” “American Exploiters in a small German Town,” and “The Overcoming of Degeneration.”

- The essay was first published in Schall und Rauch 1, no. 3 (February 1920): 1–2. The English translation of this passage can be found in Richard Sheppard, Modernism Dada Postmodernism (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2000), 180.

- “Die Gesetze der Malerei,” in Thater-Schultz, Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, vol. 2, 696–98. See also Crockett, German Post-Expressionism, 47–48.

- Mario Bacchelli, “Note,” Valori plastici 2, nos. 3–4 (March–April 1920): 39.

- See note 26.

- See Crockett, German Post-Expressionism, 47.

- For Prampolini’s role in organizing two exhibitions of Expressionist and Novembergruppe artists in Rome and their political ramifications, see Maria Elena Versari, “I rapporti internazionali del Futurismo dopo il 1919,” in Il Futurismo nelle Avanguardie. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Milano del 4–6 febbraio 2010, Palazzo Reale, Sala delle Otto Colonne, ed. Walter Pedullà (Rome: Edizioni Ponte Sisto, 2010), 577–606.

- Bollettino quindicinale della Casa d’Arte Italiana, no. 1 (October 15, 1920); File “4.1.3., Rom. Novembergruppe 23.10.1920,” Hannah Höch Archiv, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin. Höch’s handwritten note is found on page two of this periodical and reads: “Edizioni Futuriste di ‘Poesia’. Rarefazioni. Parole in libertà Milano – Corso Venezia – 1915.” Höch’s copy of the periodical is reproduced in Thater-Schultz, Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, vol. 2, 706–07.

- See Thater-Schultz, Hannah Höch. Eine Lebenscollage, vol. 1, 1889–1918, 87. In a handwritten note on the Futurist manifesto, Höch stated that she received it from Prampolini.

- “2 Nummern von BLEU in Mantova, Marinetti in Milano. Tzaria [sic] von Konstantinopel über Neapel Rom nach Paris. Severini in Paris? Carra in Paris! Chiriko wird Akademikprofessor.” Handwritten note in the artist’s diary, not reproduced in the multivolume edition of her archive; Hannah Höch – Tagebucher, 1920, Hannah Höch Archiv, Berlinische Galerie.

- See Mario Bacchelli, “Note (Marzo–Aprile 1920): Accademia,” Valori plastici 2, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1920): 63.

- [Telesio] Interlandi, “Dadà,” Noi e il mondo. Rivista mensile della Tribuna, no. 10 (October 1, 1920): 750. Höch purchased a copy of this issue (now held in her archive) at a newsstand in Rome.

- Ibid., 750.

- Italo Tavolato, “La maschera della meccanica,” Valori plastici 2, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1920): 49–52.

- Carlo Carrà, “Il rinnovamento della pittura italiana (parte IV),” Valori Plastici 2, nos. 5–6 (May–June 1920): 55.

- For this issue, see Versari, “I rapporti internazionali del Futurismo dopo il 1919.”

- George Grosz, “Zu meinen neuen Bildern” (November 1920) Das Kunstblatt 5, no. 1 (January 1921): 14. For a slightly different English translation, see Voices of German Expressionism, ed. Victor H. Miesel (New York: Harry N. Abrams and Prentice-Hall, 1970), 185.

- Ibid.

- The text was published in installments in the following issues of De Stijl: vol. 4, nos. 5 (June 1921), 6 (June 1921), and 8 (August 1921); vol. 5, no. 6 (June 1922); vol. 6, nos. 3–4 (May–June 1923) and 6–7 (1924).

- See Joost Baljeu, Theo van Doesburg (New York: Macmillan, 1974), 47; Craig Eliason, The Dialectic of Dada and Constructivism: Theo van Doesburg and the Dadaists, 1920–1930 (PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2002), 88–122; and Michael White, “Van Doesburg: A Counter-life,” in Constructing a New World: Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde (London: Tate Publishing 2009), 72. On van Doesburg’s relations with Italian artists, see also Marguerite Tujiin, Mon cher ami … Lieber Does … Theo van Doesburg en de praktijk van de internationaleavant-garde. Een beschouwing over de avant-garde in de jaren 1916–1930, gevolgd door eenbecommentarieerde uitgave van de correspondentie tussen Van Doesburg en Alexander Archipenko, Tristan Tzara, Hans Richter en Enrico Prampolini (PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2003), https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.209367.

- Among the scholars of van Doesburg, Craig Eliason was the first to correctly identify and analyze Camini’s relationship to Carrà. See his “Theo Van Doesburg: Italian Futurist?,” in The Low Countries: Crossroads of Cultures, ed. Thomas F. Shannon, Ton J. Broos, and Margriet Bruyn Lacy (Münster: Nodus 2006), 47–56. See also Giovanni Lista, “Van Doesburg et les futuristes,” in Theo van Doesburg, ed. Serge Lemoine (Paris: Sers, 1990), 150–57.

- Eliason, “Theo Van Doesburg: Italian Futurist?”

- The painting is reproduced in an unpaginated table at the very beginning of the journal. It is immediately followed by Carrà’s essay. See Carlo Carrà, “Il quadrante dello spirito,” Valori Plastici 1, no. 1 (November 15, 1918): 1–2.

- Carlo Carrà, “De Wijzerplast Van Den Geest,” trans. Mary Robbers, De Stijl 2, no. 7 (May 1919): 75–77. See also Eliason, The Dialectic of Dada and Constructivism, 101.

- See Maria Elena Versari, “The Style and Status of the Modern Artist: Archipenko in the Eyes of the Italian Futurists,” in Alexander Archipenko Revisited: An international perspective, Proceedings from the Archipenko Symposium, Cooper Union, New York City, September 17, 2005 (New York: The Archipenko Foundation, 2008), 18–22.

- Alexander Archipenko, Carousel Pierrot (1913), plaster, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- Carlo Carrà, “Il quadrante dello spirito,” 2.

- Ibid.

- Theo van Doesburg, “Rondblik,” De Stijl 3, no. 9 (July 1920): 80.

- See Eliason, The Dialectic of Dada and Constructivism, 123.

- Camini, “Caminoscopie,” 68–69. English translation in Eliason, The Dialectic of Dada and Constructivism, 126.

- Ibid., 70. English trans., 127.

- Ibid.

- For some of these issues, see Maria Elena Versari, “Futurist Machine Art, Constructivism and the Modernity of Mechanization,” in Futurism and the Technological Imagination, ed. Günter Berghaus (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009), 149–76.