Appendix: 1963, “An Exhuming Job:” Medardo Rosso, Margaret Scolari Barr, and the MoMA Exhibition

Francesco Guzzetti Francesco Guzzetti Medardo Rosso, Issue 6, December 2021https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/medardo-rosso/

A detailed reconstruction of Medardo Rosso (1858-1928) (curated by Peter Selz, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, October 2 – November 23, 1963), with a description of every work included within the exhibition.

Medardo Rosso (1858-1928), curated by Peter Selz

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, October 2 – November 23, 1963

The exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York consisted of thirty-three pieces (twenty-eight sculptures and five drawings). The reconstruction of the exhibition has been conducted by trying to recover as much information as possible in order to identify precisely each work on view. The information provided in the exhibition checklist and the more recent survey of the artist’s body of work, as determined in the catalogue raisonné of sculpture, don’t often coincide.1 In light of these discrepancies, a decision was made to provide the “official” title and date of each work, according to the catalogue raisonné, in the first line of each entry. The title and date assigned in the exhibition follow in the second line. Many of the works on view at MoMA are not included in the catalogue raisonné. The date and information of catalogued sculptures are provided according to their respective entries in the catalogue raisonné. In all other cases, the title is followed by the date of the first version in square brackets. In the case of sculptures from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the presumable date of cast is also added, according to the object files provided by the museum.2. With regards to the five drawings, a decision was made to provide the more recent titles and dates under which they have been exhibited and published. Materials and size of each work are updated to the more recent sources of information, unless no evidence of the sculptures was found, in which case the size follows the one indicated in the exhibition checklist. Essential information about provenance and relevant bibliography and exhibition history is provided in case of works documented in the catalogue raisonné. In all other cases, the entries include all information concerning the history and the installation of the works in the exhibition, which was primarily gathered through archival research. The sorting order of the entries, and their division between sculptures and drawings, comply with the checklist of the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, as published in a brochure printed on that occasion.3

- Sculpture

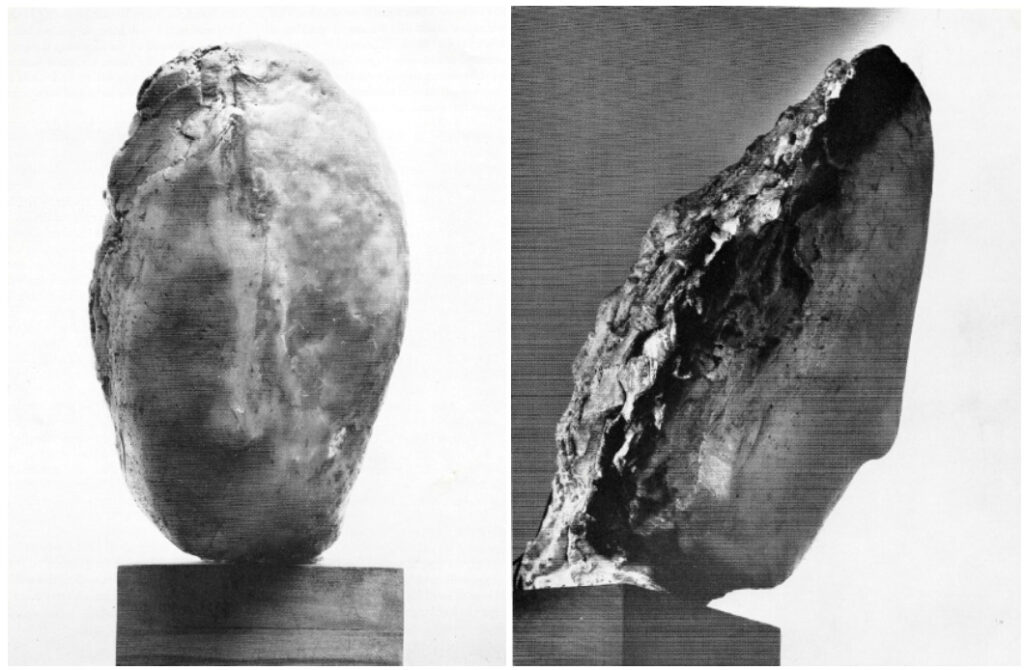

- Innamorati sotto il lampione, [1883] (Fig. 6)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Kiss under the Lamppost, 1882

Bronze, h. 18 7/8 inches

Current whereabouts unknown

Medardo Rosso, “Innamorati sotto il lampione”, [1883] (no. 1)

The piece was lent by Jack E. Berizzi. The name of the collector and the provenance of the piece are rather obscure. Jack E. Berizzi was the son of Stefano Berizzi (1881-1960), an Italian immigrant who came to the United States in 1900 and founded the silk importing firm Berizzi Brothers along with his brother Luigi (who changed his name to Louis).4 Jack worked in the textile industry and designed fabrics for firms such as Moss Rose Mfg. Co.5 The Berizzis were originally from Northern Italy, as attested by the fact that Louis Berizzi studied business in Milan before migrating.6 They were prominent figures in the Italian community in New York, as Stefano also directed the Banca Commerciale Italiana Trust Company.7 It has been impossible so far to determine how the bronze of Innamorati sotto il lampione ended up in the collection of Jack E. Berizzi. He might have inherited it from his father. It could be a coincidence, but it is worth noting, in this respect, that Margaret Scolari Barr included the name of Stefano Berizzi among the people she wanted to acknowledge in her book on Rosso, “for investigation, documentation, assistance in procuring photographic material, and reporting references in books and periodicals I had not thought of exploring.”8 Even if it has not been possible to confirm it so far, it can be argued that Stefano Berizzi was related to Guido Berizzi, an acquaintance of Medardo Rosso and his son, Francesco. Guido Berizzi owned works by Rosso, such as Aetas Aurea and Enfant juif in wax, which were sold through Galleria Il Milione in Milan to Galleria Odyssia in New York in 1964.9 One can assume kinship between Stefano and Guido Berizzi, considering that the latter was an Italian accountant who sat on the board of “Stagionatura Anonima,” a silk manufacturing firm in Milan.10 Another artwork is documented in the collection of Jack E. Berizzi, which is a small scale bronze by the 19th century sculptor Giuseppe Grandi. The sculpture was a cast of La Pleureuse (The Mourning Woman), published by Scolari Barr in her monograph under the title of Misery.11 It was photographed by the technicians at the Museum of Modern Art on the occasion of the exhibition.12 It was not a sculpture one might easily buy in New York, so it might have been inherited from the family as well.13 The version of Innamorati sotto il lampione once owned by Berizzi is consistent with the bronze that Francesco Rosso donated to Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome in 1931 and could therefore be considered one of the copies cast at the foundry Strada, according to the reconstruction of the history of the piece and its variants compiled by Paola Mola in the catalogue raisonné.14 Thanks to the photograph reproduced in the book by Scolari Barr and the information concerning the size, the sculpture can be identified with the bronze auctioned at Sotheby’s in 1996.15

- Birichino, [1882]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Street Boy (Gavroche), 1882

Bronze, h. 13 7/8 inches

Current whereabouts unknown

Although credited to the collection of Paul Josefowitz in the catalogue and exhibition brochure, the sculpture was borrowed from his father, Samuel.16 The businessman gathered an extensive collection of 19th century and early 20th century art, including a major selection of works by the School of Ponte-Aven, which was donated to the Indianapolis Museum of Art.17 Paul followed in his father’s footsteps, by expanding the collection and eventually becoming director of the magazine Apollo.18 A few documents concerning the version of Birichino in the Josefowitz collection are held at Archivio Medardo Rosso in Milan, according to which the piece was acquired from Galleria Ferrario in Milan in 1950.19 Based on the documentation provided, the sculpture is a posthumous bronze cast, made by MAF foundry in Milan.20 Such an identification is confirmed by an installation view of the exhibition and the illustration of the piece in the monograph by Scolari Barr, which is mistakenly credited as belonging to the collection of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome.21 In fact, the work does not correspond to the version held in that museum. On the other hand, the round base on the lower part of the illustrated piece is distinctive of the replicas cast at MAF foundry. It could be assumed, then, that the piece illustrated in the book is the version owned by Josefowitz.

- Amor materno, 1883-86 (see Fig. 4 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Mother and Child Sleeping, 1883

Bronze, 13 7/8 x 11 7/8 inches

Current whereabouts unknown22

The piece came from the collection of Cesare Fasola. It is the only known version of this subject, and was probably the first bronze to be cast from the plaster. Knowing that the piece was unique, Fasola was concerned about the practice of making replicas after Rosso’s works. In fact, in his correspondence with “Bruno Tartaglia,” the company which shipped all the loans from Italy, he specified that a condition should be included in the agreement, that no copies of any kind were made after the work.23 It was one of the most relevant works in the exhibition, and it was illustrated in the book by Scolari Barr.24

- Sagrestano, [1883]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: The Sacristan, 1883

Glazed plaster on a wooden base, h. 15 ¾ inches

Private collection

The work was lent by Peridot Gallery in New York, where it had already been exhibited on the occasion of the retrospective of Medardo Rosso’s sculpture, running from December 14, 1959, to January 16, 1960.25 It is first documented in a photograph authenticated by Giorgio Nicodemi, the former director of the museums of the city of Milan, who recorded its provenance from the Mascioni collection.26 The name of Mascioni should be associated to the figure of Enrico Mascioni, a businessman who owned and managed some of the most important hotels in Milan in the early 20th century.27 An avid collector, Mascioni gathered an extensive group of works, mostly by major representative of the modern tendencies in Italian art of the late 19th century, such as Scapigliatura and Divisionismo.[28]28 More recently, the piece has been consigned by the estate of Louis Pollack, owner of Peridot Gallery, to Sotheby’s and sold at auction in London.29 Paola Mola compiled a detailed expertise and description in 2018, in which she argued that the work should be considered a replica not made by the artist.30 It is illustrated in Scolari Barr’s volume.31

- Carne altrui, 1895-1896 [1883-1884]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: The Flesh of Others, 1883

Bronze, 16 x 13 x 10 ¾ inches

Washington, DC, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.32

The work was borrowed from the collection of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, who had acquired it from Peridot Gallery in 1961.33 By the time of the exhibition, the sculpture had already been presented in the show of the collection of sculptures gathered by Hirshhorn, held at the Guggenheim Museum from October 2, 1962 to January 6, 1963, and featured in the accompanying catalogue.34 It originally belonged to the Uruguayan artist Milo Beretta, who was a pupil and assistant of Rosso in Paris until 1898, when he moved back to his native country. In the monograph by Scolari Barr, published on the occasion of the exhibition, a wax version of the sculpture is reproduced.35

- Portinaia, [1883-84]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Concierge, 1883

Wax over plaster, 14 5/8 x 12 ½ x 6 ½ inches

New York, The Museum of Modern Art36

The work was acquired by the museum from the Peridot Gallery in May 1959.37 It was originally owned by the famous composer Umberto Giordano, whom Rosso addressed in the dedication that he inscribed over the surface of the sculpture. It was included in the selection exhibited at Peridot Gallery between 1959 and 1960, on the occasion of first retrospective of the Italian artist in the United States.38 It is illustrated in Scolari Barr’s monograph.39

- Impressione d’omnibus, [1884-1885]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Impression in an Omnibus, 1883-1884

Wax over plaster, 17 x 32 ¼ x 14 inches

Minneapolis, The Minneapolis Institute of Art

The work was borrowed from the private collection of Samuel Josefowitz.40 By the time of the exhibition, Josefowitz had already tried to sell it by consigning it to Frumkin Gallery.41 It was actually Allan Frumkin who facilitated the contact between Selz and Josefowitz.42 It was sold at auction at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet in 1968,43 and finally purchased by the Minneapolis Institute of Art in 1970.44 In the checklist published in the brochure circulating on the occasion of the exhibition, the caption of the piece is accompanied by the following note: “The original version of this sculpture, comprising five figures, was smashed on its way to an exhibition in Venice in 1887. This seems to be a later reconstruction by the artist.”45 In the monograph, Scolari Barr recounted the story of the original work, its destruction, and focused on the surviving photographs of it, but didn’t mention this sculpture at all. In a confidential report sent to Peter Selz, Scolari Barr explained why she wouldn’t include it in the book. Recalling the circumstances of her first encounter with the sculpture in the collection of the dancer Rosa Sofia Moretti in Rome, where she went in 1960 “hot on the trail of MR [Medardo Rosso]”,46 the art historian articulated her doubts about the authenticity. The uncertainty surrounding the piece was such that she could not help but admit that “fake or genuine, […] I believe the work is very poor in quality. Consequently I do not want to reproduce it or refer to it in the book for anything that I could honestly say would tend to disparage it.”47 Barr’s suspicion would be somehow confirmed in the following years: as of today, the work is considered fake by the estate of the artist.

- Aetas aurea, ([1885-1887] probably cast c. 1946-50) (see Fig. 5 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: The Golden Age, 1886

Wax over plaster, 20 11/16 x 19 5/16 x 11 1/4 inches

Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

The work was lent by Joseph H. Hirshhorn. The collector had acquired it in 1961 from Peridot Gallery, which had it on consignment by Clotilde (Tilde) Longoni Rosso, the widow of Francesco, the sculptor’s son.48 The agent Anita de Cristofaro acted as intermediary in the transaction between the family and Louis Pollack, the owner of Peridot Gallery. According to the information provided by the Hirshhorn Museum, it should be considered a cast made by Francesco Rosso, approximately in the second half of the 1940s. It was first exhibited in 1962, on the occasion of the exhibition of Hirshhorn’s collection of sculptures at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.49

- Enfant au sein, [1889], cast after the version realized in 1910-14

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Child at the Breast, 1889

Bronze, h. 13 5/8 inches

Current whereabouts unknown

Little information has been found so far with regard to this piece, which was lent by Peridot Gallery. It was not included in the retrospective held at the gallery in 1959-60. Based on the illustration published in the monograph by Scolari Barr, it’s a cast of the plaster made by the artist between 1910 and 1914, in which the mother’s head was taken out of the composition.50 Considering that the plaster was in the collection of the artist’s family, and that a bronze is still today at Museo Rosso in Barzio, it might be assumed that the work was a posthumous cast made by Francesco Rosso and given on consignment to Louis Pollack by the family.51 Further research should be done, though, to confirm such a conclusion.

- Malato all’ospedale, [1889]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Man in a Hospital, 1889

Plaster, 9 1/16 x 10 1/4 x 11 1/2 inches

Washington, DC, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

By the time of the exhibition, the work had already been acquired by Joseph H. Hirshhorn and included in the exhibition of his sculpture collection, held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York a few months before.52According to the information provided by the museum, it should be considered a version cast by Rosso himself. It was originally owned by Guido Berizzi, who supposedly acquired a few sculptures directly from the artist.53 Berizzi gave it on consignment to Louis Pollack of the Peridot Gallery in 1961, when it was acquired by Hirshhorn.54 A photograph of the work is reproduced in Scolari Barr’s book.55

- Henri Rouart, 1889

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Portrait of Henri Rouart, 1890

Bronze, 40 ½ x 22 7/8 x 13 5/8 inches

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna.56

The piece was lent by the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome. It was cast by the artist’s son, Francesco, who gifted it to the museum in 1931. Palma Bucarelli, the director of the museum in Rome, was extremely helpful in securing loans for the exhibition from Italian museums. Bucarelli was hesitant about shipping wax sculptures due to conservation issues, so she refused to lend the wax mask of the Rieuse.57 Scolari Barr included an image of the piece among the illustrations of her monograph.58

- Rieuse, 1894 [1890] (see Fig. 5 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Petite rieuse (head), 1890.

Bronze, 14 ½ x 7 7/8 x 10 ¼ inches

Paris, Musée Rodin.59

The piece was famously given by Rosso to Auguste Rodin after the 1893 exhibition at the Bodinière in Paris. Rosso took in exchange a half-life size version of the Torso by the French sculptor. As explained in the following entry, it was not the original intention of Selz to borrow this piece from Musée Rodin. Although not reproduced, the work is mentioned by Scolari Barr in light of its significance in the relationship between Rosso and Rodin.60

- Rieuse, 1890 (see Fig. 4 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Petite rieuse (mask), 1890

Bronze, h. 8 5/8 inches

Private collection

In the original intentions of Peter Selz, the wax mask of the Rieuse held at Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome should have been exhibited alongside a version of the head in bronze, owned by Peridot Gallery.61 When the museum director, Palma Bucarelli, denied the loan, Selz changed ideas entirely on how to present Rosso’s Rieuse. The head was borrowed from Musée Rodin in Paris, while a bronze version of the mask of the Rieuse was borrowed from Peridot Gallery.62 The piece was first presented in the first retrospective of Medardo Rosso held at the gallery in 1959-60.63 It should be therefore identified with the bronze version of the sculpture which has recently resurfaced. According to Paola Mola, the sculpture is a posthumous cast made by Francesco Rosso64.

- Grande Rieuse, [1891-1892] (see Fig. 5 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Grande Rieuse (mask), 1891

Wax over plaster, h. 10 ¾ inches

Current whereabouts unknown

The mask of the Grande Rieuse hung next to Aetas aurea in the vitrine installed at the center of the exhibition room, as depicted in an installation view. It was lent by Count Vittorio Cini, an important Italian politician, based in Venice, who gathered an extensive collection, with special focus on old masters.65 The work is no longer part of the collection. Besides the documents held in the exhibition files at the archives of the Museum of Modern Art, thus far no additional documentation has been found concerning the provenance of the piece and its presence in the Cini collection. In her book, Scolari Barr decided to illustrate the head of Grande Rieuse instead of the bust, too.66 The art historian chose the photograph of the version held at the Civica Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan.67

- Enfant au soleil, [1891-1892]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Child in the Sun, 1892

Bronze, 13 1/4 × 8 1/4 × 7 inches

Milwaukee, Milwaukee Art Museum

The work was initially lent by Louis Pollack of the Peridot Gallery. Nonetheless, Pollack had already sold it to the Milwaukee Art Museum by the time when the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art opened. The museum in Milwaukee agreed to keep the sculpture in the exhibition, with the new credit line.68 It had already been presented in the retrospective of Medardo Rosso, taking place at Peridot Gallery between 1959 and 1960.69Apparently, the work was consigned to Pollack by Pietro Biffi, a Milanese friend and collector of Medardo Rosso in the artist’s later years.70 Biffi was also involved in the loans for the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.71 Further research should be done to confirm the provenance and assess the quality of the piece. It is illustrated in the monograph by Scolari Barr.72

- Enfant juif, [1893]

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Jewish Boy, 1892

Wax over plaster, 8 7/8 x 6 5/8 x 6 inches

New York, The Museum of Modern Art

The piece was lent by Peridot Gallery. It was subsequently acquired by Harriet H. Jonas, and finally entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of Jonas’ bequest in 1974.73 So far, it has been impossible to determine the provenance of the sculpture before its consignment to Peridot Gallery. This specific version is also illustrated in Scolari Barr’s book.74

- Enfant à la Bouchée de pain, [1897], cast c. 1943-44

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Baby Chewing Bread, 1893

Wax over plaster, 19 7/8 x 19 1/4 x 7 1/8 inches

Washington, D.C., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

At the time of the exhibition, the piece belonged to Joseph H. Hirshhorn and had already been presented, with the rest of his collection of sculptures, at the Guggenheim Museum in 1962-63.75 On that occasion, it was assigned the title Child in Poorhouse. According to the object files held in the archives of Hirshhorn Museum, the collector bought it from Peridot Gallery on February 1, 1962.76 The cast was most likely made by the artist’s son, Francesco, in the 1940s. It was consigned to Galleria Santo Spirito in Milan in 1946 and included in the first posthumous retrospective of Medardo Rosso organized at the gallery. It’s listed in the catalogue under the title “Bambino all’asilo dei poveri.”77 On that occasion, it was acquired by the painter Ezio Pastorio, one of the founders of the gallery, as attested by the affidavit held in the museum archive78. The dealer Bruno Grossetti, who founded Galleria dell’Annunciata in Milan, bought the sculpture from Pastorio and sold it to Pollack. A photograph of the work is published in the book by Scolari Barr.79

- Enfant malade, [1895] (see Fig. 4 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Sick Boy, 1893

Wax over plaster, 12 x 9 ¼ x 7 inches, including base

Washington, D.C., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

The sculpture was lent by Peridot Gallery. Despite the lack of documentation and the absence of illustrations in Scolari Barr’s monograph,80 it could be presumably identified with the version of Enfant malade which was acquired by Joseph H. Hirshhorn at auction in 1968.81 Based on the installation views of the exhibition, the sculpture was mounted on a rectangular wooden base, which made it stand higher than the bronze version displayed nearby. The wax in the Hirshhorn collection has an extremely similar base. In addition, stylistic elements and the size included in the caption of the work published in the brochure of the MoMA exhibition coincide. Before being acquired at auction, this sculpture had been consigned in the late 1950s to Peridot Gallery, where it was exhibited in the Rosso retrospective between 1959 and 1960. Enfant malade is reproduced without the base in the catalogue produced by the gallery, but the spots in the lower part of the wax layer and the diagonal crack running through the forehead coincide between the photograph and the sculpture currently at the Hirshhorn Museum.82 According to the catalogue of the Parke-Bernet sale in 1968, it was originally owned by Giorgio Chierichetti, an important Milanese industrialist and patron of the arts.83 The provenance could explain the presence of a metal plate attached to the wooden base with an inscription in Italian, which includes the artist’s name, the title of the work and the reference to the city of Paris. On a side note, Josefowitz bought the wax Impressione d’omnibus at the same auction in 1968.84

- Enfant malade, [1895] (see Fig. 4 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Sick Boy, 1893

Bronze, h. 9 ¾ inches

Current whereabouts unknown

At the time of the exhibition, the piece belonged to the collection of Samuel Josefowitz. It was still credited to the same collection a few years later, when a photograph of the piece was illustrated in the survey on sculpture of the 19th and 20th century, which Fred Licht authored in 1967 for the series of books on the history of Western sculpture edited by John Pope-Hennessy.85 The sculpture had to be photographed by the photographer of the Museum of Modern Art when it was loaned to the exhibition.86 That image was reproduced in the book by Scolari Barr.87

- La conversazione, [1899] (see Fig. 4 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Conversation in the Garden, 1893

Bronze, 15 x 12 3/8 x 26 ¼ inches

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporeanea.88

The bronze was the second work by Rosso borrowed from the Galleria Nazionale in Rome, after the Henri Rouart. It was given to the museum in Rome by Francesco Rosso in 1931. The reason why it was requested after the Rouart stems from a mistake made by Selz.89 In fact, the collector Gianni Mattioli was first asked for the loan of his version of La conversazione. Selz assumed that Mattioli owned a bronze, but it was actually a wax, and the collector denied the loan due to concerns about the conservation of the piece.90 Having already secured the support of Palma Bucarelli, the director of Galleria Nazionale, in expediting the loan procedures, Selz therefore turned to her and asked for the bronze version owned by the museum in Rome. The wax from the Mattioli collection was illustrated in Scolari Barr’s monograph anyway, with two photographs taken in different light conditions, to emphasize the texture of its rough surface.91 The particular of the standing figure to the left was also reproduced, alongside the images of Bookmaker and L’uomo che legge, to demonstrate Rosso’s effort to redefine the depiction of human figure within the atmosphere, in comparison with Rodin’s Balzac.92

- Bookmaker, [1894] (Fig. 7)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Bookmaker, 1894

Wax over plaster, 17 ½ x 13 x 14 inches

New York, The Museum of Modern Art.93

Medardo Rosso, “Bookmaker”, [1894] (no. 21)

- L’uomo che legge, [1894], cast 1960

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Man Reading, 1894.

Bronze, 10 x 11 ¼ x 11 inches

New York, The Museum of Modern Art98

The sculpture entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in 1960.99 It was acquired from Mario Vianello-Chiodo, who was granted by Rosso himself the right to make copies of a few sculptures that the artist sent to him.100 Vianello-Chiodo commissioned the execution of bronzes from the Fonderia Artistica Veronese between 1959 and 1960.101 It is correctly credited as a posthumous cast in the caption of the plate published in Scolari Barr’s book.102 The art historian published the image another time, alongside a detail of La conversazione and Bookmaker, in comparison with the photograph of Rodin’s Balzac.103

- Yvette Guilbert, 1895

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Plaster, 16 3/8 x 12 5/8 x 9 ½ inches

Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro104

The sculpture was borrowed from the museum of modern art in Venice through the mediation of Palma Bucarelli, the director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome.105 When Selz followed up on the loan request with Guido Perocco, the director of the museum in Venice, he was notified that an official approval request was submitted and pending.106 Due to the delay in receiving a response, Selz asked Bucarelli for the loan of the wax version of Yvette Guilbert, which belongs to the collection of the museum in Rome.107 Bucarelli was hesitant due to conservation issues, but supported the loan request to Perocco, who finally agreed. On a side note, Perocco asked in return for the support of the Museum of Modern Art in a loan request for Vittore Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.108 The panel should have been exhibited in the major Carpaccio retrospective held in Venice in 1963. Selz sent a letter to Theodore Rousseau, curator of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum encouraging the loan, which was ultimately denied due to conservation issues.109 Yvette Guilbert was one of the major loans to the exhibition, and thus illustrated in Scolari Barr’s monograph.110

- Madame X, 1896 (Fig. 8)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Madame X, 1896

Wax over plaster, 11 ¾ x 7 ½ x 9 ½ inches

Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro.111

Medardo Rosso, “Madame X”, 1896 (no. 24)

The piece was borrowed from the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, the museum of modern art in Venice. It was originally gifted to the museum by the artist himself in 1914, after the eleventh edition of the Venice Biennale. When it arrived at the Museum of Modern Art, the mounting of the sculpture was found to be insecure. Following consultation with Guido Perocco, the support was replaced.112 Alongside Yvette Guilbert, it was the major loan to the exhibition, and was illustrated and extensively discussed in the monograph by Scolari Barr.113

- Madame Noblet, 1897 (see Fig. 5 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Madame Noblet, 1897

Bronze, 20 x 19 ¾ x 13 ¾ inches

Milan, Civica Galleria d’Arte Moderna114

Selz asked Paolo Arrigoni, the director of Civica Galleria d’Arte Moderna, the museum of modern art of the city of Milan, for two loans, Femme à la voilette and Madame Noblet. Arrigoni was concerned about the fragility of the wax and denied the loan of the first piece, but agreed to lend the latter, which is a bronze.115 The sculpture was given to the museum in Milan by Francesco Rosso in 1953. In the book authored by Scolari Barr, the photograph of the dark wax version held at the museum in Ca’ Pesaro in Venice is reproduced. The work is mistakenly listed as a bronze and credited to the museum in Milan in the accompanying caption.116

- Head of a Young Woman, 1901 (?) (see Fig. 5 of main article)

Wax over plaster, h. 15 ¾

Columbus, Columbus Museum of Art

The sculpture, referred to as Head of a Young Woman in the exhibition checklist, is listed as a fake in the inventory held at Archivio Rosso in Milan. The authenticity had already been disputed in the catalogue of the retrospective held in Milan in 1979.117 At the time of the exhibition, it was still on consignment to Peridot Gallery, where it was included in the artist’s retrospective in 1959-60.118 That exhibition marked the first known presentation of the sculpture. The collectors Howard D. and Babette Sirak, who gathered an extensive collection of impressionist and modern art, acquired the sculpture shortly after the exhibition at MoMA, as attested by its inclusion in the catalogue of the exhibition of the Sirak collection, published in 1968.119 In 1991, the whole collection was given to the Columbus Museum of Art, including Head of a Young Woman.120 In her monograph on the artist, Scolari Barr published a photo of the sculpture and briefly discussed it in a footnote, in which she noted that it “formerly belonged to Alberto Capozzi, an agent of the Grubicy brothers in Paris.”121 It is probably Scolari Barr who changed the date of the piece from 1897 to 1901. In the correspondence with Giorgio Nicodemi, the art historian discussed the provenance of the piece and asked for his hypotheses about the moment when it might have been realized by the artist.122 Scolari’s troubles in positioning the sculpture within Rosso’s oeuvre help understand her decision to mention it in a footnote, instead of including it in the body text of the book. No evidence about Alberto Capozzi and his connection with Grubicy has been found so far.

- Ecce Puer, [1906], cast c. 1958-59 (Fig. 9)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Ecce Puer, 1906-07

Wax over plaster, 17 1/4 x 13 3/4 x 10 3/8 in.

Washington, D.C., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Medardo Rosso, “Ecce Puer”, [1906] cast c. 1958-59 (no. 27)

- Ecce Puer, [1906] (see Fig. 4 of main article)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Ecce Puer, 1906-07

Bronze, h. 18 5/8 inches

Current whereabouts unknown

The sculpture was lent by Pietro Biffi, the same person who gave the bronze of Enfant au soleil on consignment to Peridot Gallery.125 Biffi was presented as a Milanese friend and collector of Medardo Rosso in the artist’s later years by Giorgio Nicodemi.126 The relationship with the artist is confirmed by a letter that Biffi himself sent to Selz, in which he agreed to lend Ecce Puer, “a bronze,” as he described it, “which, more than anything else, was especially dear to the artist, whom I had the privilege to personally meet and befriend.”127 Biffi was among the first witnesses of Rosso with whom Scolari Barr reached out at the beginning of her research on Rosso, as attested by a letter to Nicodemi, in which the art historian thanked him for introducing her to Biffi and regretted that hadn’t had his remarkable Ecce Puer photographed yet.128 Biffi was trying to sell this and maybe other works by Rosso at that time. A letter by Dorothy Dudley, the exhibition registrar, to the shipping company “Bruno Tartaglia” bears witness of Biffi’s intention to put the sculpture on sale at $ 15,000, which was the same amount as the insurance value.129 In a report sent to the museum, the shipper reminded that the return of all pieces to Italy was a preliminary and mandatory condition in the request of loans from Italy, therefore warning the museum that official permission should be submitted to the Italian Government before selling anything.130 Ecce Puer was actually returned to Biffi. According to documents held at Archivio Medardo Rosso, the artwork was later sold to the sculptor Cesare Poli, who taught at the Academy of Brera in Milan.131 Poli passed away in 1964, so, should the information be correct, the sale happened shortly after the return of the sculpture. The photograph of the work was not included in the book by Scolari Barr, who instead illustrated two wax versions, belonging to the Hirshhorn and Malbin collections.132

- Works on paper

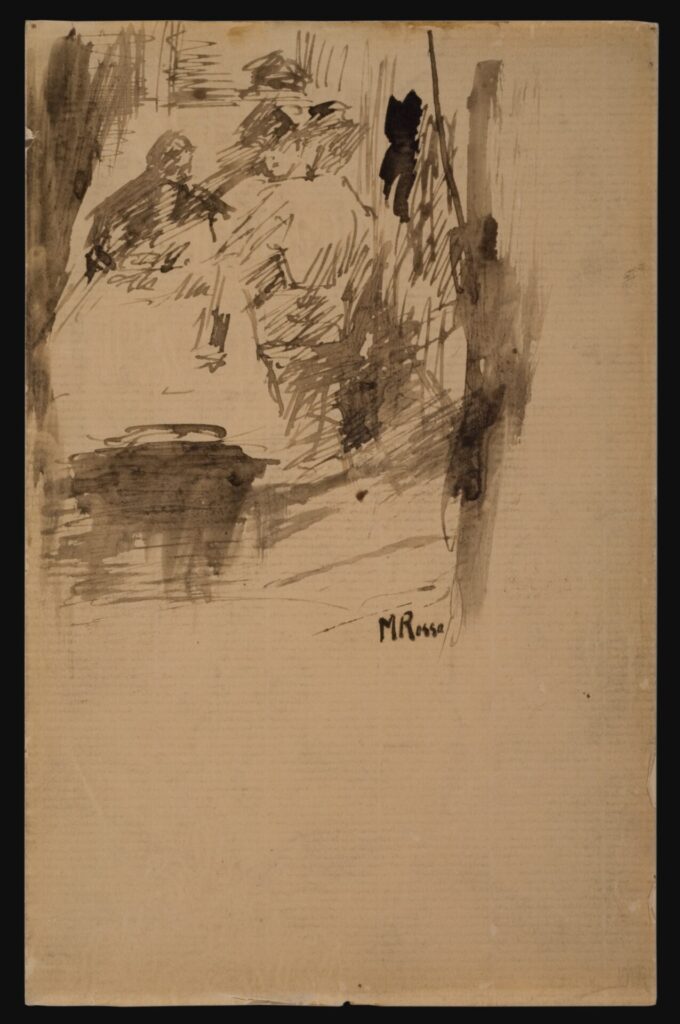

- Untitled, n.d. (Fig. 10)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: At the Café de la Roche, 1893

Ink, wash on paper, 8 x 5 ¼ inches

Private collection.133

At the time of the exhibition, the work belonged to the collection of Gianni Mattioli. The collector had already collaborated with Selz for the exhibition on Futurism, organized at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961.134 By virtue of this relationship, Mattioli was among the first collectors to whom Selz reached out for the exhibition on Medardo Rosso.135 This is one of three drawings by Rosso which Mattioli agreed to lend.136 The drawing was first illustrated in the album published on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition at Eugene Cremetti Gallery in London in 1906, which means that it was most likely shown in the exhibition as well.137 Such a prominent work on paper was also included in the solo show at Bottega di Poesia gallery in Milan in 1923, and reproduced in the accompanying catalogue under the title Effet au Café du Roches.138 Before 1963, it was reproduced in the monograph authored by Mino Borghi in 1950.139 By virtue of its relevance, Margaret Scolari Barr decided to include it in the restricted selection of artist’s sheets illustrated in her book.140

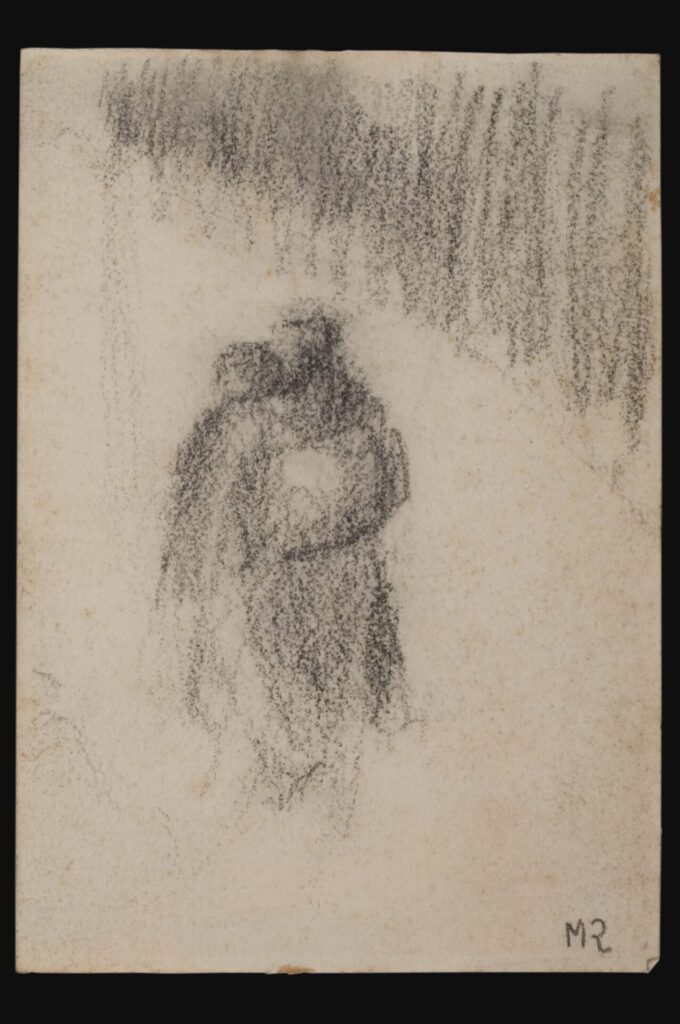

- Untitled, n.d. (Fig. 11)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: The Woods, 1893

Graphite on paper, 8 x 5 ¼ inches

Private collection141

The drawing was one of the three sheets borrowed from the collection of Gianni Mattioli. It was first published in the seminal monograph authored by Ardengo Soffici two years after the artist’s death.142 On that occasion, it was titled Giardino (Garden). It was also illustrated in the book by Mino Borghi, released in 1950.143

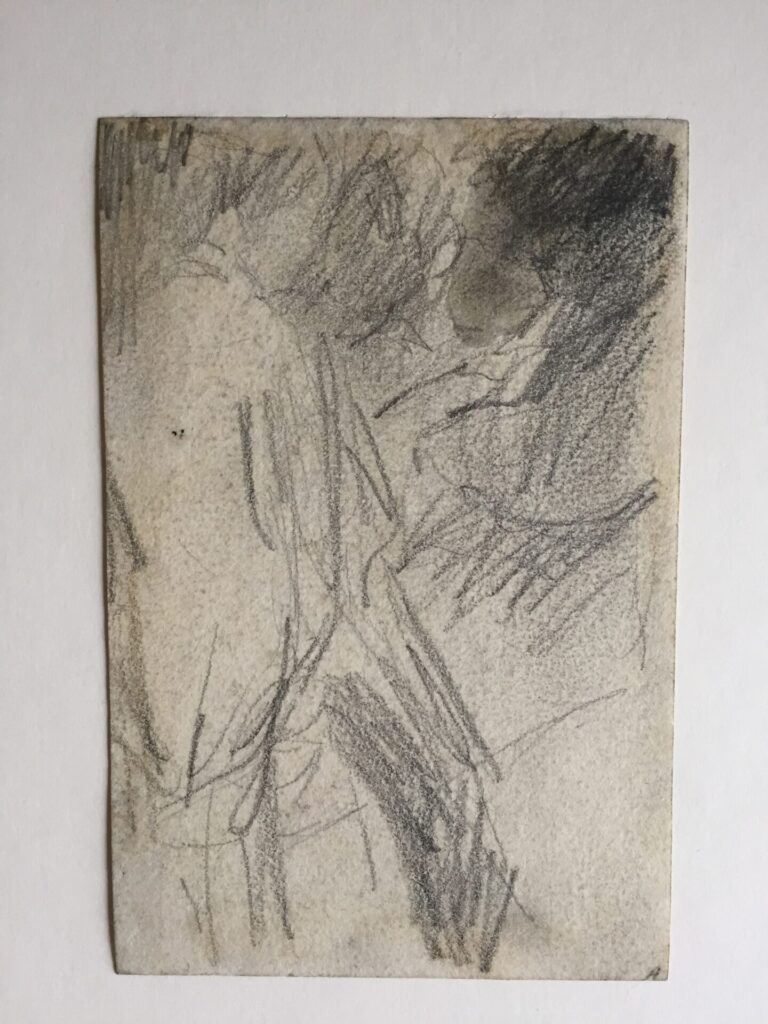

- Untitled, n.d. (Fig. 12)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Two Figures, 1893

Graphite on paper, 5 x 3 ½ inches

Private collection144

It is the third drawing lent by Gianni Mattioli. By the time of the exhibition, a photograph of the drawing had already been included among the many illustrations of the 1950 book by Mino Borghi.145

- A Londra in un bar, n.d. (Fig. 13)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Bar in London, 1906

Graphite on paper, 4 ¾ x 3 1/8 inches

Private collection

The drawing was borrowed from Peridot Gallery. It was first published in the catalogue of the Rosso exhibition held at Bottega di Poesia in Milan in 1923.146 On that occasion, it was assigned the French title Effet dans un bar à Londres. According to Giorgio Nicodemi, who presented it in 1959, this drawing and a view of Trafalgar Square – which was also shown at the Museum of Modern Art147 – originally belonged to Rosso’s friend Pietro Biffi, who lent the bronze Ecce Puer to the exhibition.148 The two sheets were exhibited together at the retrospective of Rosso held at Peridot Gallery in 1959-60.149 More recently, they were both sold at auction at Sotheby’s.[150]150

- Parco con fontana, n.d. (Fig. 14)

Title and date assigned in the exhibition: Trafalgar Square, 1906

Graphite on paper, 4 1/8 x 6 ¾ inches

Private collection

Together with the previous drawing, this work was borrowed from Peridot Gallery. Giorgio Nicodemi published the two drawings with a provenance from the collection of Pietro Biffi.151 Soon afterwards, they were exhibited at Peridot Gallery.152 More recently, the drawings were both sold at auction at Sotheby’s.153 The sheet was first illustrated in the album published by Cremetti Gallery in London in 1906, on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition.154 Scolari Barr published a photograph of the drawing in her survey on the relationship between Rosso and Etha Fles in 1962.155 In the personal files of Fles, in fact, Scolari Barr found a photograph that Rosso had taken of the drawing, which served as a postcard sent to Fles. By marking the profile of a statue on the right side of the sheet with a cross, Rosso gave Fles a rendezvous by a monument in Trafalgar Square in London.156The following year, the art historian would reproduce the drawing once again in her monograph on the artist.157

Bibliography

I mostra postuma milanese di Medardo Rosso. Milan: Edizioni Galleria Santo Spirito, 1946.

XIII catalogo d’arte: Mostra personale delle opere di Medardo Rosso. Milan: Bottega di Poesia, 1923.

20th Century Italian Art, London, Sotheby’s, October 16, 2009.

XXV Biennale di Venezia: Catalogo. Venice: Bruno Alfieri, 1950.

Annuario industriale della Provincia di Milano. Milan: Unione fascista degl’industriali della Provincia di Milano, 1937.

“Art: Rosso Re-evaluated.” Time 82, no. 15 (October 11, 1963).

Ashton, Dore. “A Sculptor of Mystical Feeling.” The New York Times 109, no. 37,227 (December 27, 1959): X17.

Ashton, Dore. “Medardo Rosso—A Long – Obscured Talent.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 85, no. 325 (November 24, 1963): 5C.

Bedarida, Raffaele, Davide Colombo, and Silvia Bignami, eds. “Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art”,” Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020): https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of-exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/.

Bignami, Silvia, and Davide Colombo, “Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby’s Grand Tour of Italy,” Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020): https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alfred-h-barr-jr-and-james-thrall-sobys-grand-tour-of-italy/.

Biografia Finanziaria Italiana: Guida degli amministratori e dei sindaci delle società anonime, delle casse di risparmio, degli enti parastatali ed assimilati, ecc. Rome: Tip. Laboremus, 1935.

Borghi, Mino. Medardo Rosso. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1950.

Boussamba, Jennifer. “Décès du collectionneur Paul Josefowitz.” Connaissance des arts (May 14, 2013): https://www.connaissancedesarts.com/arts-expositions/deces-du-collectionneur-paul-josefowitz-11893/.

Burnham, Jack. Beyond Modern Sculpture. New York: George Braziller, 1968.

Burnham, Jack. “Sculpture’s Vanishing Base.” Artforum 6, no. 3 (November 1967): 49-55.

Caramel, Luciano, and Paola Mola Kirchmayr, eds. Mostra di Medardo Rosso (1858-1928). Milan: Società per le Belle Arti ed Esposizione Permanente, 1979.

Caramel, Luciano. “La prima attività di Medardo Rosso e i suoi rapporti con l’ambiente milanese.” Arte Lombarda 6, no. 2 (July-December 1961): 265-76.

Chipp, Herschel B. “A Method for Studying the Documents of Modern Art.” Art Journal 26, no. 4 (Summer 1967): 369-76.

Claris, Edmond, ed. De l’impressionnisme en sculpture. Paris: Éditions de la “Nouvelle Revue”, 1902.

Contemporary Art, Milan, Sotheby’s, 25 November 2009.

Dobrzynski, Judith H. “Indianapolis Museum Buys 30 Gauguins From Swiss Collector.” The New York Times 148, no. 51,345 (November 18, 1998): E5.

du Plessix, Francine. “Books: Forty for Christmas.” Art in America 51, no. 6 (December 1963): 108-17.

“Elected by Banca Commerciale.” The New York Times 82, no. 27,501 (May 11, 1933): 25.

Elsen, Albert E. Auguste Rodin. New York—Garden City: The Museum of Modern Art—Doubleday, 1963.

Fles, Etha. “Medardo Rosso.” Elsevier’s Geïllustreed Maandschrift, no. 11 (November 1919).

Gamble, Antje K. “Exhibiting Italian Modernism after World War II at MoMA in “Twentieth Century Italian Art”.” Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020): https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/exhibiting-italian-modernism-after-world-war-ii-at-moma-in-twentieth-century-italian-art/.

Geist, Sidney. “Salut! Apollinaire.” in The Best in Arts: Arts Yearbook 6, edited by James R. Mellow (1962): 96-98.

Genauer, Emily. “Experiments of the Present Form Our View of the Past.” New York Herald Tribune (December 20, 1959).

Giedion-Welcker, Carola. Contemporary Sculpture: An Evolution in Volume and Space. New York: George Wittenborn, Inc., 1955.

Giedion-Welcker, Carola. Moderne Plastik. Elemente der Wirklichkeit; Masse und Auflockerung. Zurich: Girsberger, 1937.

Goldwater, Robert, and Marco Treves, eds. Artists on Art: From the XIV to the XX Century. New York: Pantheon Books, 1945.

“Good Design: 1954.” Arts & Architecture 71, no. 2 (February 1954): 16.

Guzzetti, Francesco. “Femme à la voilette, 1895-1910. Impressions in France, Germany, Great Britain and Italy,” in Medardo Rosso. Femme à la voilette (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2018): 41-59.

Hecker, Sharon. A Moment’s Monument: Medardo Rosso and the International Origins of Modern Sculpture.Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.

Hecker, Sharon. “Medardo Rosso’s First Commission.” Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1125 (December 1996): 817-22.

Important 19th-20th Century Sculpture, New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries, April 4, 1968.

Impressionist and Modern Art, Day Sale, London, Sotheby’s, February 2, 2005.

Impressionist and Modern Art, n. N08968, Sotheby’s, New York, March 13, 2013.

Impressionist, Modern and Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, n. 1529, Sotheby’s, New York, February 7, 1996.

Jewell, Edward Alden. “Recent Books on Art.” The New York Times 95, no. 32,292 (June 23, 1946): 4X.

Kozloff, Max. Jasper Johns. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1968.

Kozloff, Max. “The Equivocation of Medardo Rosso.” Art International 7, no. 9 (November 1963): 46-47.

Kramer, Hilton. “‘An Ambiance … All Too Rare’.” The New York Times 120, no. 41, 224 (December 6, 1970): D29.

Kramer, Hilton. “Medardo Rosso.” Arts 34, no. 3 (December 1959): 30-37.

Kramer, Hilton. “Medardo Rosso at The Modern.” Arts Magazine 38, no. 1 (October 1963): 44-45.

Licht, Fred. Sculpture: 19th and 20th Centuries. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1967.

Lewis Gaillet, Lynée. “Museum of Modern Art’s “Margaret Scolari Barr Papers”.” Peitho. Journal of the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rethoric & Composition 22, no. 3 (Spring 2020): https://cfshrc.org/article/museum-of-modern-arts-margaret-scolari-barr-papers/.

“Louis Berizzi.” The New York Times 100, no. 34,024 (March 21, 1951): 33.

Marchi, Anna. “Notiziario: antichità.” Domus, no. 408 (November 1963): n.p.

Medardo Rosso: Impressions. London: Eugene Cremetti, 1906.

Medardo Rosso. New York: Center for Italian Modern Art, 2015.

Medardo Rosso: Ten Bronzes. New York—Lugano-London: Peter Freeman—Amedeo Porro Fine Arts, 2016.

Messer, Thomas, and H.H. Arnason, eds. Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1962.

Modern and Contemporary Art, Chicago, Wright, 1 June 2003.

Mola, Paola, and Fabio Vittucci, eds. Medardo Rosso: Catalogo ragionato della scultura. Milan: Skira, 2009.

Mola, Paola. Rosso: Trasferimenti. Milan: Skira, 2006.

Mola, Paola. “Trasferimenti: fotografia e scultura nell’opera di Rosso.” L’uomo nero, no. 9 (2012): 40-61.

Morris, Robert. “Anti Form,” Artforum 6, no. 8 (April 1968): 33-35.

Nicodemi, Giorgio. “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso.” L’Arte 24, no. 4 (1959): 375-78.

Oral history interview with Margaret Scolari Barr relating to Alfred H. Barr, 1974 February 22-May 13. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-margaret-scolari-barr-relating-to-alfred-h-barr-13250#overview.

Page, Addison Franklin, ed. The Sirak Collection. Louisville: The Speed Art Museum, 1968.

“Painting and Sculpture Acquisitions January 1 through December 31, 1959,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art27, nos. 3-4 (1960): 1-40.

Preston, Stuart. “Art and Pathos: Medardo Rosso Shown At the Modern Museum.” The New York Times 113, no. 38,606 (October 6, 1963): X 17.

Preston, Stuart. “Museum of Modern Art Displaying 28 Sculptures by Rosso.” The New York Times 113, no. 38,602 (October 2, 1963): 38.

R.F.C. “New York: Una grande mostra di Medardo Rosso.” Emporium 139, no. 830 (February 1964): 68-71.

“Ricevuto e visto.” D’Ars Agency 5, no. 2 (February 1964): 174.

Ritchie, Andrew C., ed. Sculpture of the Twentieth Century. New York: The Museum of Modern Art—Simon and Schuster, 1952.

Ritchie, Andrew C. Sculpture of the Twentieth Century. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1952.

Rudikoff, Sonya. “New York Letter.” Art International 6, no. 9 (November 1962): 60-63

Schiff, Bennett. “In the Art Galleries.” New York Post (December 20, 1959): M12

Scolari Barr, Margaret. “Medardo Rosso and His Dutch Patroness Etha Fles.” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 13 (1962): 217-251.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. Medardo Rosso. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1963.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. ““Our Campaigns”.” The New Criterion (Summer 1987): 23-74.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. “Reviving Medardo Rosso.” Art News 58, no. 9 (January 1960): 36-38, 66-67.

Selz, Peter, ed. New Images of Man. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959.

Soby, James Thrall, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr, eds. Twentieth-Century Italian Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949.

Soffici, Ardengo. Medardo Rosso. Florence: Vallecchi, 1929.

Somarè, Enrico, ed. Raccolta Enrico Mascioni. Milan: Galleria Pesaro, 1931.

Staudacher, Elisabetta, ed. Capitani di un esercito: Milano e i suoi collezionisti. Milan: Gallerie Maspes, 2017.

“Stefano Berizzi.” The New York Times, vol. CX, no. 37,536 (October 31, 1960): 31.

Taylor, Joshua C., ed. Futurism. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1961.

T.B.H. [Thomas B. Hess]. “Reviews and Previews: Medardo Rosso.” Art News 62, no. 7 (November 1963): 14.

The first exhibition in America of sculpture by Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928. New York: Peridot Gallery, 1959.

Tillim, Sidney. “Month in Review.” Arts Magazine 38, no. 2 (November 1963): 28-31.

Treves, Marco, “Maniera, the history of a word,” Marsyas 1 (1941): 69-88.

W.R. “The Hirshhorn Collection at the Guggenheim Museum.” Art International 6, no. 9 (November 1962): 34-37.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: Catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit.

- I wish to thank Hannah Green for checking the information and providing me with updated records on the provenance of the works in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

- Medardo Rosso, exhibition brochure, MoMA Exhs., [729.2]. MoMA Archives, NY).

- See the obituary in The New York Times 110, no. 37,536 (October 31, 1960): 31.

- Fabrics designed by Berizzi were included in 13th edition of the Good Design exhibition, held at 1954 at the Museum of Modern Art, see “Good Design: 1954,” Arts & Architecture 71, no. 2 (February 1954): 16.

- See the obituary in The New York Times 100, no. 34,024 (March 21, 1951): 33.

- See the announcement in The New York Times 82, no. 27,501 (May 11, 1933): 25.

- Margaret Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1963): 6.

- The two sculptures are mentioned in the registry of Galleria Il Milione (handwritten notes held at Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan). The provenance is confirmed by the inclusion of the name of Berizzi among the collectors who owned a version of both the works, listed by Mino Borghi in his monograph on Rosso in 1950, see Mino Borghi, Medardo Rosso (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1950): 65, 66. Aetas Aurea was finally acquired by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY (https://www.albrightknox.org/artworks/19666-eta-doro).

- Biografia Finanziaria Italiana: Guida degli amministratori e dei sindaci delle società anonime, delle casse di risparmio, degli enti parastatali ed assimilati, ecc. (Rome: Tip. Laboremus, 1935): 97. For a complete account on “Stagionatura Anonima,” see Annuario industriale della Provincia di Milano (Milan: Unione fascista degl’industriali della Provincia di Milano, 1937): 479-89.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 66.

- Typewritten form “Staff Photograph Requisition,” March 11, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- The sculpture could be identified with the bronze sold at auction at Sotheby’s New York in 2013, with provenance indicating that it was gifted by the artist to the grandfather of the owner who gave it on consignment, see Impressionist and Modern Art, n. N08968, Sotheby’s, New York, March 13, 2013, lot 110.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: Catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 235-36.

- Impressionist, Modern and Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, n. 1529, Sotheby’s, New York, February 7, 1996, lot 102. The photograph of Berizzi’s sculpture is reproduced in Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 13.

- Loan receipt, May 28, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Judith H. Dobrzynski, “Indianapolis Museum Buys 30 Gauguins From Swiss Collector,” The New York Times 148, no. 51,345 (November 18, 1998): E5.

- Jennifer Boussamba, “Décès du collectionneur Paul Josefowitz,” Connaissance des arts (May 14, 2013), see the following link: https://www.connaissancedesarts.com/arts-expositions/deces-du-collectionneur-paul-josefowitz-11893/.

- Copy of receipt to Josefowitz on letterhead of Galleria Ferrario, November 20, 1950. Milan, Archivio Medardo Rosso.

- Handwritten note over the copy of loan receipt of the sculpture for the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, held in Milan, Archivio Medardo Rosso.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 15.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: Catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 236-37, no. 6b.

- Cesare Fasola, typewritten letter to Bruno Tartaglia, January 18, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Cesare Fasola, typewritten letter to Bruno Tartaglia, January 18, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- The first exhibition in America of sculpture by Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928 (New York: Peridot Gallery, 1959): cat no. 1.

- Photograph with handwritten note on the back, Tortona, Archivio della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona, Fondo Giorgio Nicodemi (from now on the citation will be as follows: Tortona, Fondazione CR)

- Saverio Almini, “Enrico Mascioni,” in Elisabetta Staudacher, ed., Capitani di un esercito: Milano e i suoi collezionisti (Milan: Gallerie Maspes, 2017): 84-85.

- Enrico Somarè, ed., Raccolta Enrico Mascioni (Milan: Galleria Pesaro, 1931).

- 20th Century Italian Art, London, Sotheby’s, October 16, 2009, lot 7.

- Expertise by Paola Mola, February 6, 2018, Milan, Archivio Medardo Rosso.

- Scolari Barri, Medardo Rosso, cit., 22.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 243-44, no. I.10c.

- According to the provenance detailed by the Hirshhorn Museum, the piece was acquired from Peridot Gallery on March 20, 1961, see https://hirshhorn.si.edu//collection/artwork/?edanUrl=edanmdm%3Ahmsg_66.4405.

- Thomas Messer, H.H. Arnason, eds., Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1962): 30, cat. no. 404.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 23. According to the caption, the location of that version was unknown. Nonetheless, the sculpture closely resembles the wax version donated by Francesco Rosso to Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome in 1931. This assumption seems to be confirmed by the credit of the image, which is the Gabinetto fotografico nazionale, the national photographic institute, in Rome, which provided all the photographs of sculptures in the collection of Galleria Nazionale.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 352, cat. no. III.8d.

- Purchase order, May 5, 1959, MoMA, Department of Painting and Sculpture, Museum Collection Files 614.1959. Documents consulted at Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan.

- The first American retrospective, cit., n.p., cat. no. 2.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 24.

- On the figure of Josefowitz, see the entry concerning Birichino above.

- Samuel Josefowitz, typewritten letter to Peter Selz, September 12, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Allan Frumkin, typewritten letter to Peter Selz on letterhead “Allan Frumkin Gallery, Inc.,” July 26, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.3], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Important 19th-20th Century Sculpture, New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries, April 4, 1968, lot 127.

- “Medardo Rosso: El Loch and Impression in an Omnibus”, MIA Bulletin 59, (1970): 45-47.

- Medardo Rosso, exhibition brochure, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Margaret Scolar Barr, typewritten report to Peter Selz, undated, MoMA Exhs., [729.4], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Ibid.

- According to the object files, the sale was finalized on June 5, 1961, see https://hirshhorn.si.edu//collection/artwork/?edanUrl=edanmdm%3Ahmsg_66.4407. In view of the date, the piece can’t be identified, as it has sometimes been done, with the wax version of Aetas aurea exhibited in the first retrospective of Rosso at Peridot Gallery in 1959-60 (The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 3). That version was in fact in private hands until 2005, when it was sold at a Sotheby’s auction, see Impressionist and Modern Art, Day Sale, London, Sotheby’s, February 2, 2005, lot 439.

- Messer, Arnason, Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection cit., 228, cat. no. 406.

- Scolari Barri, Medardo Rosso, cit., 29.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 272-73, cat. nos. I.22c.-I22e.

- Messer, Arnason, Modern Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection, cit., 31, cat. no. 407.

- For information about Guido Berizzi and his connection with Medardo and Francesco Rosso, see the entry of Innamorati sotto il lampione above. The object files held in the archive of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden mention an affidavit signed by Berizzi, which confirms the acquisition directly from the artist.

- For information about Guido Berizzi and his connection with Medardo and Francesco Rosso, see the entry of Innamorati sotto il lampione above. The object files held in the archive of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden mention an affidavit signed by Berizzi, which confirms the acquisition directly from the artist.

- Scolari Barri, Medardo Rosso, cit., 31.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 362, no. IV.6.

- Palma Bucarelli, typewritten letter to Peter Selz, March 15, 1963, MoMA Exhs., 729.2], MoMA Archives, NY

- Palma Bucarelli, typewritten letter to Peter Selz, March 15, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 277-78, no. I.24b.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 43, 72.

- That version was published by Nicodemi in 1959, see Giorgio Nicodemi, “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso,” L’Arte 24, no. 4 (1959): 377. It was subsequently exhibited at Peridot Gallery, see The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 4. More recently, it was auctioned in 2003 as part of the collection of the Chicago dealer Bud C. Holland (Modern and Contemporary Art, Chicago, Wright, 1 June 2003, lot 105).

- In a memorandum for the registrar office of the museum concerning the loan of the piece, it’s specified that it was “in exchange for bronze head Rieuse, which should be delivered to the Peridot Gallery sometime next week” (Typewritten memorandum, September 12, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY).

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 5.

- Expertise by Paola Mola, October 2, 2014, Milan, Archivio Medardo Rosso

- Typewritten letter to Peter Selz, on letterhead “Amministrazione Vittorio Cini, Venezia”, March 2, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 34.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato della scultura, cit., 285-86, cat. no. I.25d.

- Laurence V. Donovan, typewritten letter to Dorothy Dudley, on letterhead “Milwaukee Art Center,” September 20, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 7.

- This is how Biffi is described by Giorgio Nicodemi, see Nicodemi, “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso,” cit., 376.

- See the entry of the bronze version of Ecce Puer below.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 37.

- Provenance information held at Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 38.

- Messer, Arnason, Modern Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection, cit., 228, cat. no. 407

- See the provenance online: https://hirshhorn.si.edu//collection/artwork/?edanUrl=edanmdm%3Ahmsg_66.4410

- I mostra postuma milanese di Medardo Rosso (Milan: Edizioni Galleria Santo Spirito, 1946): cat. no. 9.

- Ezio Pastorio, affidavit, March 10, 1960, information provided by Hannah Green.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 39.

- An early photograph of the wax in the collection of the Staatliche Kunstammlungen in Dresden is reproduced in the book, see ivi, 40.

- See the provenance online: https://hirshhorn.si.edu//collection/artwork/?edanUrl=edanmdm%3Ahmsg_86.4049

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 10.

- Important 19th-20th Century Sculpture, New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries, sale no. 2679, April 4, 1968, lot 136.

- See the entry above.

- Fred Licht, Sculpture: 19th and 20th Centuries (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1967): 158, 323, cat. no. 147.

- T. Varveris, typewritten form on letterhead “The Museum of Modern Art”, April 25, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 40.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 357, cat. no. III.20.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Palma Bucarelli, April 26, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Gianni Mattioli, typewritten letter to Peter Selz on letterhead “Gianni Mattioli”, April 20, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Scolari Barri, Medardo Rosso, cit., 41.

- Ibid., 73.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 367, cat. no. V.5a. Due to lack of knowledge at the time of the realization of the catalogue, the piece is erroneously registered as the bronze cast by Vianello-Chiodo and given personally to Alfred Barr. That sculpture stayed in Barr’s private collection, and Margaret Scolari bequeathed it to the Princetion University Art Museum.

- “Painting and Sculpture Acquisitions January 1 through December 31, 1959,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 27, nos. 3-4 (1960): 8, 39.

- Purchase order, October 20, 1959, MoMA, Department of Painting and Sculpture, Museum Collection Files, 673.1959. Copy of object files held at Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan. See the list of works shipped from Clotilde Rosso to Louis Pollack, June 9, 1959, Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan.

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 9.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., n.p., 44, 73.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 367, cat. no. V.4a.

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Painting and Sculpture Acquisitions, 1960,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 28, nos. 3-4 (1961): 13, 58.

- Alfred H. Barr, letter to Mario Vianello-Chiodo, December 14, 1959, MoMA, Department of Painting and Sculpture, Museum Collection Files SC89.1960. Copy of object files held at Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 365-66.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 45.

- Ibid., 74.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 317-18, cat. no. I.32a

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Palma Bucarelli, May 14, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Guido Perocco, April 11, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.3], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Palma Bucarelli, May 9, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Guido Perocco, April 11, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.3], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Theodore Rousseau, April 11, 1963; Theodore Rousseau, typewritten letter to Peter Selz on letterhead “The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” April 17, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.3], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 47.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 319-20, cat. no. I.33.

- Guido Perocco, cable, September 12, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 50.

- Mola, Vittucci, Medardo Rosso: catalogo ragionato, cit., 324-26, cat. no. I.36b. The sculpture was also exhibited at CIMA, see Medardo Rosso (New York: Center for Italian Modern Art, 2015): 26-27.

- Paolo Arrigoni, typewritten letter to Peter Selz on letterhead “Comune di Milano – Castello Sforzesco,” March 12, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 52-53.

- Luciano Caramel, Paola Mola Kirchmayr, eds., Mostra di Medardo Rosso (1858-1928) (Milan: Società per le Belle Arti ed Esposizione Permanente, 1979): 145, cat. no. 43.

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 11. The work was dated 1897 in the catalogue.

- Addison Franklin Page, ed., The Sirak Collection (Louisville: The Speed Art Museum, 1968): 52, cat. no. 10.

- See the provenance indicated on the museum website: http://5095.sydneyplus.com/final/Portal/Default.aspx?lang=en-US

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 77. The sculpture is illustrated ibid., 79.

- Margaret Scolari Barr, typewritten letter to Giorgio Nicodemi, January 9, 1962, Tortona, Fondazione CR.

- The acquisition dates to January 25, 1963, see https://hirshhorn.si.edu//collection/artwork/?edanUrl=edanmdm%3Ahmsg_66.4411

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, n.p.

- See the entry above.

- Nicodemi, “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso,” cit., 376.

- Pietro Biffi, handwritten letter to Peter Selz, March 10, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Margaret Scolari Barr, typewritten letter to Giorgio Nicodemi, January 24, 1960, Tortona, Fondazione CR.

- Dorothy H. Dudley, typewritten letter to “Bruno Tartaglia” company, July 8, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.6], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Ditta Bruno Tartaglia, typewritten letter to Peter Selz on letterhead “Bruno Tartaglia,” August 24, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- The work was sold to Poli through the mediation of engineer Leopoldo Zorzi, according to notes taken after a conversation with the heir of Zorzi, see handwritten notes on letterhead “Museo Medardo Rosso,” February 18, 1998, Archivio Medardo Rosso, Milan.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., n.p., 57.

- The drawing was included in the exhibition at CIMA in 2014-15, see Medardo Rosso, cit., 45.

- According to the exhibition checklist, eleven works were borrowed from the Mattioli collection, see MoMA exhibition records, 695. Futurism [MoMA Exh. #685, May 30-September 5, 1961], 685.1, digitized at the following link: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2821.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Gianni Mattioli, February 7, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Gianni Mattioli, typewritten letter to Peter Selz on letterhead “Gianni Mattioli,” February 20, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.2], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Medardo Rosso: Impressions (London: Eugene Cremetti, 1906): 37.

- XIII catalogo d’arte: Mostra personale delle opere di Medardo Rosso (Milan: Bottega di Poesia, 1923): n.p.

- Borghi, Medardo Rosso, cit., 41.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 82. The drawing is mistakenly credited to Museo Medardo Rosso in Barzio.

- The drawing was included in the exhibition at CIMA in 2014-15, see Medardo Rosso, cit., 42.

- Ardengo Soffici, Medardo Rosso (Florence: Vallecchi, 1929): 169.

- Borghi, Medardo Rosso, cit., 39.

- The drawing was included in the exhibition at CIMA in 2014-15, see Medardo Rosso, cit., 56.

- Borghi, Medardo Rosso, cit., 31.

- XIII catalogo d’arte: Mostra personale delle opere di Medardo Rosso, cit., n.p.

- See the following entry.

- Nicodemi, “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso,” cit., 376, 378. Nicodemi mentioned the publication of the two drawings in the 1929 monograph by Ardengo Soffici, but neither of them was illustrated in the book.

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 13.

- Contemporary Art, Milan, Sotheby’s, 25 November 2009, lot 252.

- Nicodemi, “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso,” cit., 376, 378.

- The first exhibition in America, cit., cat. no. 14.

- Contemporary Art, Milan, Sotheby’s, 25 November 2009, lot 251.

- Medardo Rosso: Impressions, cit., 7.

- Margaret Scolari Barr, “Medardo Rosso and his Dutch patroness Etha Fles,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, vol. 13 (1962): 234.

- The photograph is still kept in Scolari Barr’s files held at the Museum of Modern Art, see Margaret Scolari Barr Papers, [III.C.3], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, cit., 81.