Medardo Rosso’s Life-Size Works

Laura Mattioli Laura Mattioli Medardo Rosso, Issue 6, December 2021https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/medardo-rosso/

The article examines Medardo Rosso’s life-size work and its relationship to photography. Given that most works of such dimensions were lost or destroyed, Rosso’s photographs prove essential not only for the study of the works themselves, but also for unpacking the artist’s creative process and approach to his subjects. The impetus behind this study was the installation of the 2014-2015 Medardo Rosso exhibition at the Center for Italian Modern Art (New York), when the cohabitation of sculptures, drawings and photographs presented both a curatorial challenge and new insights into Rosso’s practice.

The present study on Medardo Rosso’s sculptural oeuvre was born out of a series of questions that arose as I was beginning to prepare an exhibition dedicated to his work, shown at CIMA from October 17, 2014 to June 27, 2015. I wanted to place Rosso’s drawings, photographs and sculptures (in different materials) in close quarters within the exhibition, so as to better understand the link between them.

The relationship between Rosso’s photographs and his other work is fairly straightforward: Rosso’s sculptures and drawings were the only subjects of his photographic activity. Photography was a novel elaboration of themes and images already explored by the artist: it furthered an already long and complicated creative process. Rosso never used the medium for capturing pre-existing natural objects directly. The photographs of Portinaia (doorkeper), for instance, do not depict the woman that Rosso sculpted, but Rosso’s sculpture of that woman, which bore the same title as the photograph. One could argue that this process anticipates Warhol, who painted his subjects through projected and modified photographs, and never directly.

Rosso’s drawings posed more of a challenge, as none of them refer to any of his known sculptures, nor to any specific objects. The exclusive subjects of these works are landscapes, interiors, and figures within the context of a street or a room. I found this fact rather intriguing, and thought that it should lead to a reassessment of his sculptures. Reflecting on this matter, I realized that Rosso’s life-size sculptures play a fundamental role in comprehending his body of work in its totality.Their insertion into a space creates an important, one-to-one relationship with the viewer. Critics have examined these sculptures relatively little, as they all went missing shortly after their completion, and were rarely (or sometimes never) displayed in public. Rosso, however, considered them extremely important works, as his many photographs of these sculptures testify. It is for this reason that I wished to replicate these photographs true to scale for the exhibition at CIMA, and why I placed them in the focal points of the show. I believe that they constitute an element of fundamental importance within the artist’s oeuvre.

The first life-size sculpture that Rosso created (Fig. 1) was commissioned in Milan in 1883, when the artist was only 25 years old. The work in question was a funerary monument in memory of Angelo Curletti, who had died in 1881. Piero Curletti, his son, was an industrialist and a collector of Scapigliati artists. That same year he bought one of Rosso’s first works, Innamorati sotto il lampione (Lovers uner the lamppost). The funerary monument was installed in a chapel within the Porta Ticinese Cemetery (also known as the Gentilino Cemetery) on October 31, 1883, but was removed nine days later on November 9. On November 16, Rosso was officially asked to rework the sculpture, due to the sarcastic and obscene comments it attracted. The bronze work was then perhaps modified (we only know this through a single photograph of the plaster model), and was ultimately removed in June 1900, when the entire chapel was demolished.

The monument to Angelo Curletti was the only life-size bronze sculpture that Rosso ever cast. Due to its location and unfortunate removal, art critics never got a chance to view or review it. The sculpture portrayed a young woman, lying prostrate on the ground, barefoot (her commoner’s clogs, placed nearby, bring a sense of realism to the scene). The maiden leans towards the grave beneath her, and looks through an opening in the ground; perhaps she even wails and calls the name of her dearly departed. The municipal inspector Carlo Galbiati, already having complained about the statue in 1883, had the following to say in June 1885: “the fair lady is scantily clad in a tattered hide, like Eve after committing the original sin.”1

The scandal, I think, was not attributable to the sculpture’s alleged realism, nor to its most immediate subject: a lower-class, half-naked girl, lying on top of a grave and weeping in an overtly erotic pose (at least to the viewers of the time–it is said that malice lies in the eyes of the beholder and not in the beheld). It is much more likely that the furore over the work came from its atheistic view of death: it begs an unanswerable question on the common fate of all humans, and it doesn’t seem to allow for any escatological hope.

Of particular interest is the fact that the sculpture, being life-size, might convey Rosso’s desire to engage the cemetery-goers on a personal level by encouraging an identification with the weeping figure (a universal Eve), thereby making them face existential questions on death, without the possibility of an easy consolation through religion.

Impressione di Omnibus

Immediately afterwards, between 1884 and 1885, Rosso created his second life-size sculpture in Milan.2 From what one can gather from the only extant photo of the work (Fig. 2)—which we exhibited as part of the show at CIMA— it was likely around 5 meters long. Indeed, this sculpture could be described as larger than life; it is not, however, monumental. One could go so far as to deem it an “anti-monument” at a time when both funerary and public monuments abounded not only in Italy, but also further afield. It is a testament to the extreme divergence of Rosso’s views on sculpture in respect to the official culture of the time. To Rosso, sculpture was not a paean to a series of abstract public and private virtues, or an exaltation of some idealized beauty. It was rather a medium to express life in its most humble and everyday aspects, following a poetic narrative kindred to authors such as Luigi Capuana and Giovanni Verga, exponents of the Verismo school of literature.

Impressione di Omnibus (Impression of an Omnibus) portrays the half-busts of five working-class people traveling on a “tramvai” (this was the original name of the work, instead of Omnibus). One can imagine that these passengers are traveling early in the morning, perhaps to go to work, or to go home after having spent the night out. From left to right, we can see a sleeping old man with a dangling head, a young lady with a hat, an old woman with a kerchief fashioned around her head, a (possibly) drunken man with a hat, and another old lady, resting upon herself. The group revisits the theme of the disenfranchised (“Gli ultimi”) with intensified ambition and complexity. Rosso dedicated the majority of his works to this motif, including Birichino (a young street urchin), Cantante a spasso (an unemployed man) Carne altrui (a prostitute), and Portinaia3(a doorkeeper), just to name a few. The social aspects of the work intersect with themes of progress and modernity: the “tramvai” was the earliest form of public transportation in Milan, and was implemented to meet the needs of the rapidly industrializing city and its ever-growing proletariat.4The sculpture went on to become a source of inspiration for a famous futurist work by Carlo Carrà, titled Cosa mi ha detto il tram (1911).

Critics have often compared Impressione di omnibus to the works of Honoré de Daumier, in particular, his 1839 lithograph titled Intérieur d’omnibus (Interior of an Omnibus) (Fig. 3). Although both works depict analogous characters, such as the young lady with a wide hat or the drunk, sleeping man, their spirits are quite different. The French drawing is ironic and has an air of caricature; its Italian sculptural counterpart, on the other hand, is dramatic, and almost surreal in nature. Rosso temporarily stills the bobbing and jostling passengers, showing their total isolation, despite their physical closeness to one another. These five life-size figures are placed in front of the viewer so that he might come to recognise his own everyday reality through them: a modernity that essentially forbids progress and reveals a wretched existential condition composed of strife and solitude. With this sculptural group, Rosso developed his interest for portraying the marginalized, a theme which the artist had already explored in his individual portraits and the “tipi” of his milanese period—a theme that faded after Rosso moved to Paris.

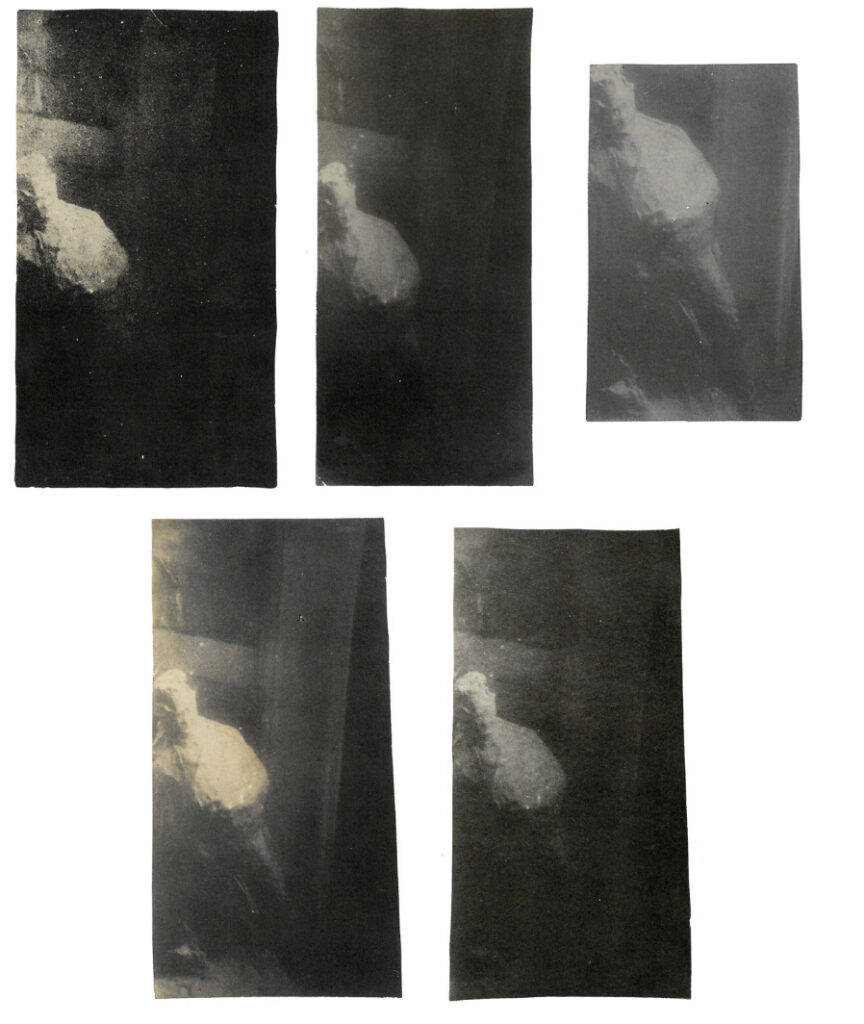

The sculpture only ever existed in plaster. Due to a lack of funds, Rosso was never able to have it cast in bronze. Considering the group to be his most important artwork, in 1887 Rosso sent it to the Esposizione Artistica Nazionale in Venice. However, due to damages sustained during transit, Intérieur d’Omnibus was returned to Rosso without ever having been publicly shown. When the artist moved to Paris in 1889, he was forced to leave it in Milan due to its considerable size and fragility. It was later destroyed by Rosso’s wife, who, fuming for having been abandoned in Milan with a young child, hacked all of her husband’s left-behind sculptures to bits. Luckily, Rosso brought a photograph of the sculpture with him to Paris and went on to re-photograph it, figure by figure, over the span of many years. In the end, roughly sixty photos of the work were created, demonstrating the importance that Rosso placed on the sculpture in understanding his artistic trajectory.

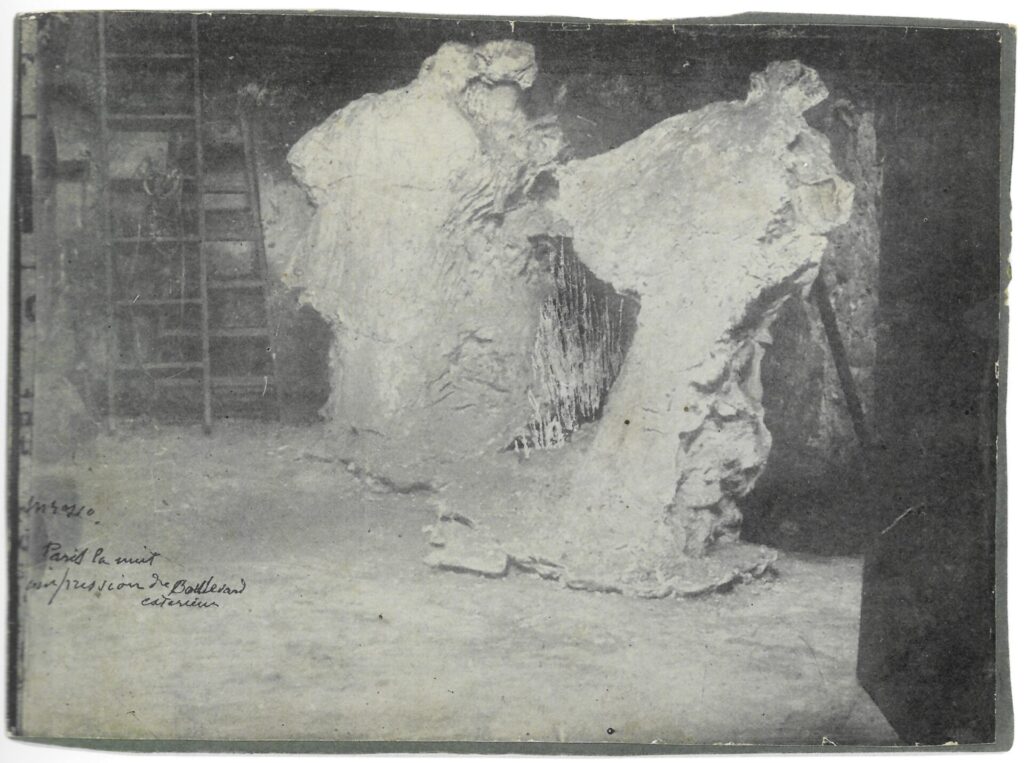

Impression de Boulevard (Paris la nuit) 5

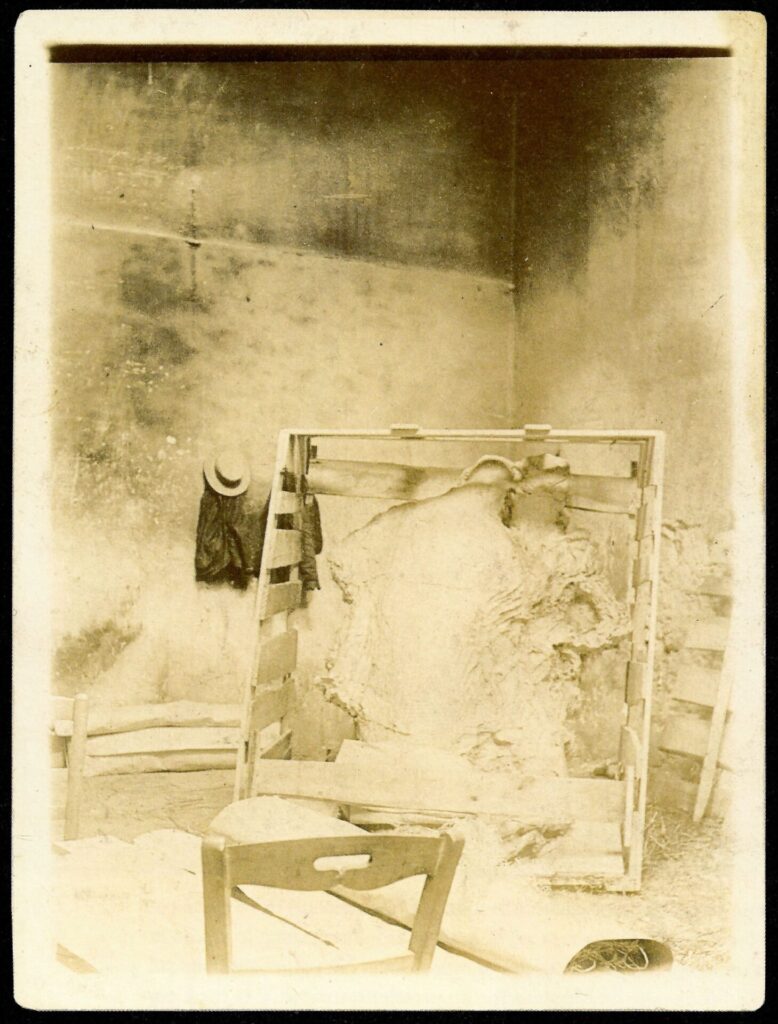

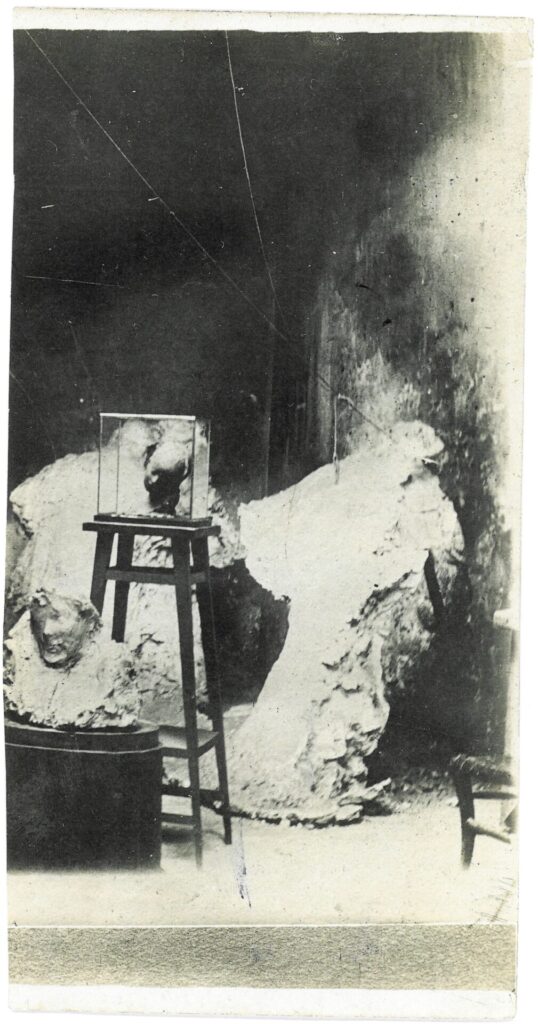

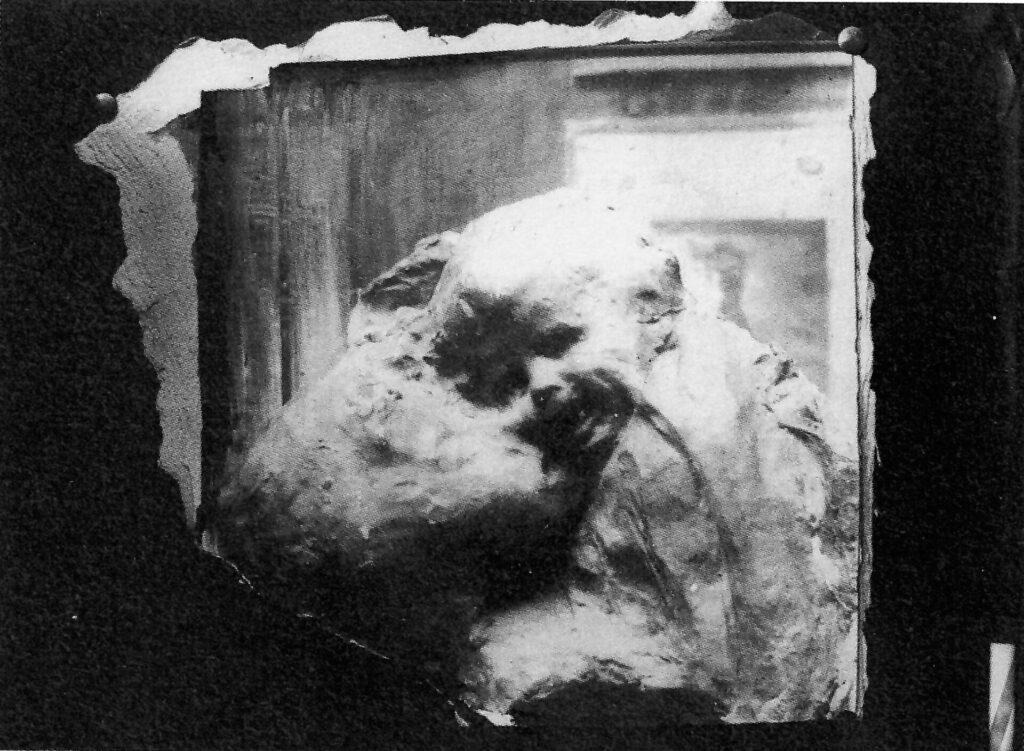

Impression de Boulevard (Paris la nuit) (Impression of a Boulevard (Paris at Night, Fig. 4) is the only life-size sculpture Rosso produced in Paris, probably in 1896-97. The work was never cast in bronze due to its size: it was too large for Rosso’s own furnace, and he couldn’t (or wouldn’t) have it cast in one of the many city foundries active at the time. The sculpture had no commission attached to it: Rosso tried, in vain, to have it shown at the 1900 Paris Exposition. It was subsequently sold between 1900 and 1902 to the doctor Luis Silvan Noblet, one of his biggest collectors (Rosso had created several portraits of Noblet’s wife). In 1902, after having purchased the sculpture, Noblet had it placed in the garden of his country house at Jessains sur Aube. There, the work was ravaged by the forces of nature, and ultimately destroyed by frost in 19296. Consequently, we only know of the work through photographs of the period: the earliest of these was taken in 1896, upon the sculpture’s arrival in Rosso’s Boulevard des Batignolles studio from the Calincourt workshop, whence it was made (Fig.5).

The sculpture portrays a couple speaking to each other in a Parisian boulevard, with the male figure portrayed with his back towards the spectator. The third figurewas likely a later evolution of the work, added shortly after the completion of the couple, and anchored to the base with an additional pouring of plaster. Though this element of the sculpture was originally called Coup de vent (Gust of Wind) due to the figure’s fluttering mantelet, critics have identified it in several different ways. The figure in question seems to be of a man (but it could be a woman, why not?) with a large overcoat, backing away from the couple. The latest extant picture of the work (Fig.6) shows how the sculpture, which Rosso himself testifies to be around two meters tall and three meters wide7, was already damaged while in the artist’s studio. Specifically, We can observe how parts of the sculpture, especially the base, are crumbling. We can also glean the work’s static issues from the eccentric pose of Coup de vent (the third figure), which had to be supported by a pole and even a ceiling anchor.

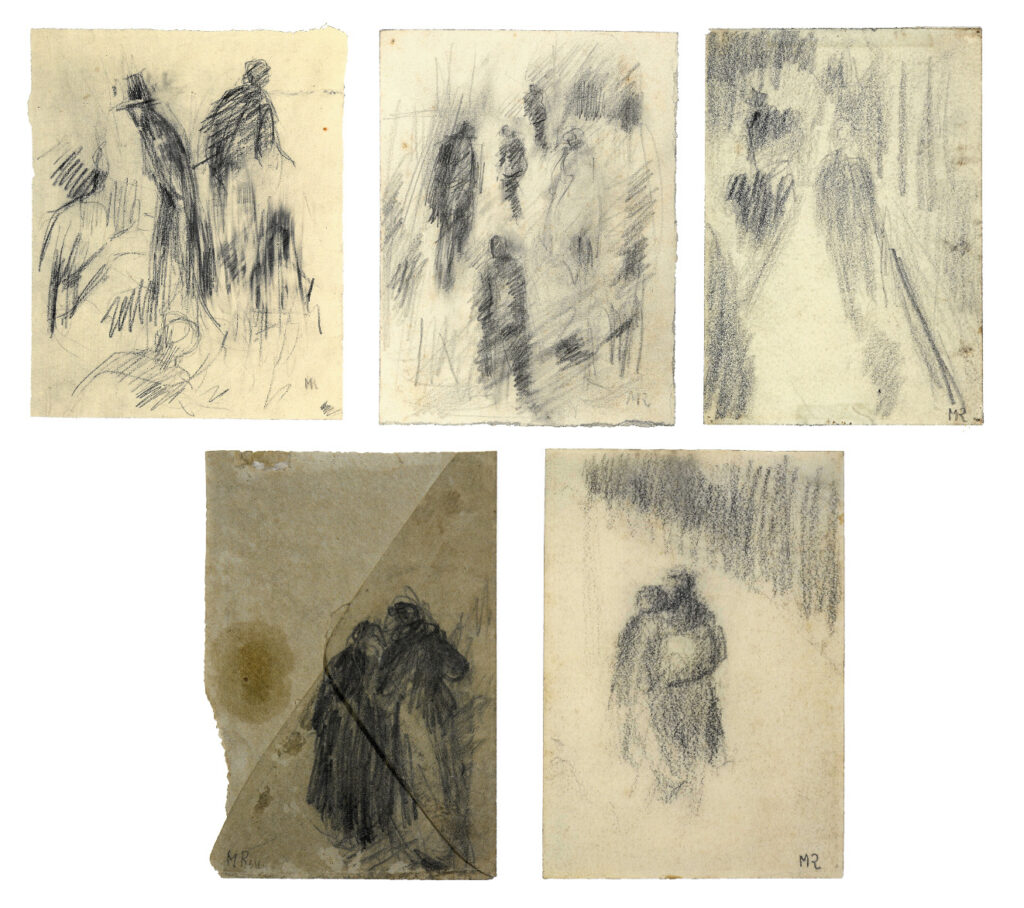

This work has been of great interest to me, as it forms a direct correspondence with the artist’s drawings. Rosso created several drawings of people walking on the street, often choosing to portray them with their backs to us (Figs.7-11). Rosso’s drawings and sculptures draw from the same tranche de vie, characterized by a viewpoint—the back of a human figure—often experienced in everyday life but seldom represented in art, as well as by movement. This style of image seems to recall Edward Degas’ work, and lead to certain futurist works, by the likes of Carlo Carrà and Umberto Boccioni (Fig. 12).

As in Rosso’s drawings, the main subject represented in Impression de Boulevard (Paris la nuit) is space: not of the Cartesian variety, however, with its unified, centralized perspective which rationalizes perception. Rosso’s space is fractured, eccentric, and dynamic. It has lost all hierarchy and rational structure.

This matter is not a question of perspective alone. Rosso’s sculptures aren’t merely an amalgam of light and shadow which captures three-dimensionality, movement, multiple perspectives. They are not merely rendering the “air” that fills the space between figures as a tangible, positive entity rather than a void—it is no wonder that Da Vinci’s aerial perspective interested Rosso so greatly. Between Medardo’s figures there exists a deep, emotion-laden dynamic that plays a fundamental role in the overall composition of his works. We can patently observe this at play in the sculpture: the man is attracted to the woman and gently places his right hand on her body, turning towards her; the woman also turns toward the man, wholly engrossed in conversation, so much so that the couple joins to form one sole mass. While the unitary form of the two figures seems to be isolated from the outside world, the third figure violently distances itself from the couple, disowning and excoriating them for their intimacy.

Many have spoken about the lack of a real pedestal in Paris la Nuit, in relation to the lack of the same in Auguste Rodin’s Bourgeois de Calais. The absence of a pedestal in the case of Rosso’s sculpture, to me, seems like a non-issue: while Rodin’s sculptural group was commissioned as a public monument by the city of Calais, Rosso neither had a commission, nor conceived this group sculpture in a monumental light. Paris la Nuit was directly inspired by everyday life; the lack of a pedestal for these figures, therefore, is less of a revolutionary act and more of a direct transferral of everyday life into sculpted form.

That isn’t to say that an interesting comparison between the two works is impossible: I find it fascinating that Rosso, contrary to Rodin, omits details such as feet, shoes and hands in his work, concentrating the entire expressive force of the sculpture within the poses of his figures.

Ritratto del Dottor Fles

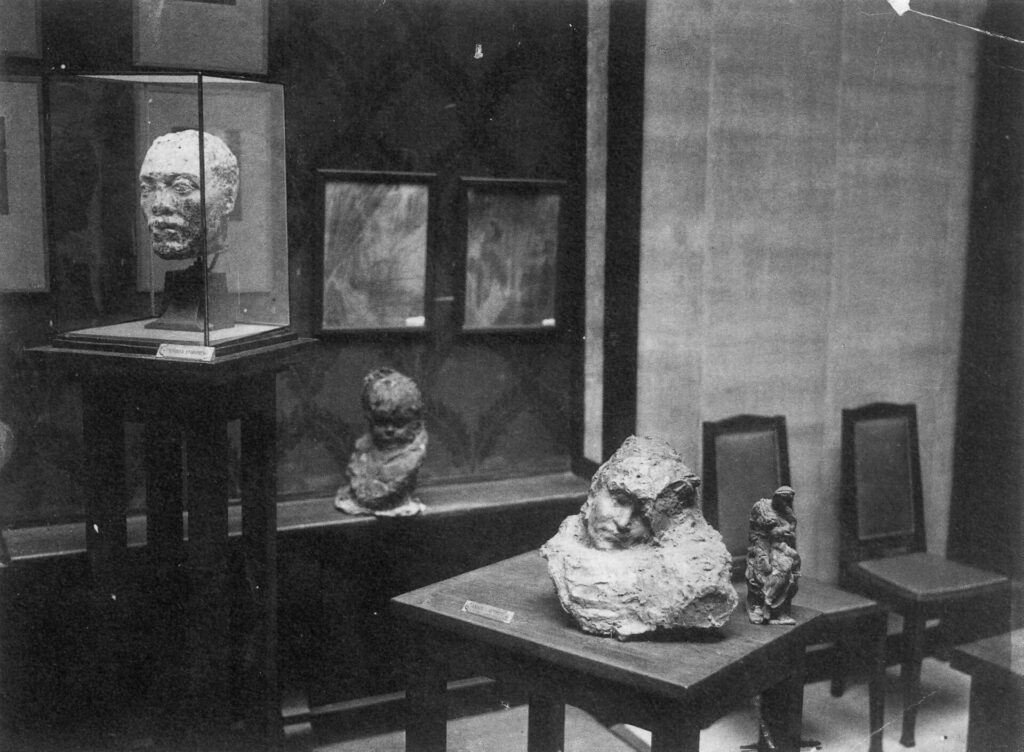

The last life-size sculpture that Rosso ever created was a portrait of the renowned oculist Joseph Alexander Fles8(father of Etha Fles) within his Utrecht home, where Rosso was received as a guest in 1901 (Fig. 16).

The work was destroyed after the sale of the house. It is known to us through one sole photograph; unfortunately, from a documentary standpoint, the image is insufficient and vague. Nevertheless, I think the image is particularly striking when placed in dialogue with the series of photographs taken of Rosso’s Bookmaker (Fig. 17) , as the interpretation of the two subjects seems to be analogous: a burly, standing masculine figure, flooded with light from behind. The old doctor is seen walking towards an open door, with tousled hair encircling a mostly bald head. His right arm is bent at the hip, as if he had something in his hand- perhaps a piece of paper or a prescription- to give to the viewer; to his right, we see an indecipherable heap of material. Additionally, we can see that all the spaces left between his limbs (e.g. between his legs) are filled with plaster. The doctor does not place his weight on the base of the work, rather, he is one with the continuous stream of plaster that follows the beam of light. Clearly, Rosso’s interest was directed at capturing the movement of the figure, as well as the effect of light and shadow on large, generalized forms.

Can the observations made thus far on Rosso’s lost life-size works influence the way in which we view his extant works, along with their associated photographs? I believe so.

Rosso came to realize that the creation of life-size works was not viable for him: he had no means to cast them, nor did he receive specific commissions for them. Small bronze works, conversely, were far easier to produce, cast, and sell, due to their high demand amongst the upper echelons of the bourgeoisie.

As such, Rosso returned to creating whole figures and groups in reduced scale. That said, these smaller works were designed to be feasibly scaled up to life-size dimensions. Photographs of these works are testament to this fact. Through the medium of photography, Rosso’s sculptures become isolated from all context, and are presented without reference to their reduced scale. Rather, several of these pictures include contrivances that aid the viewer to perceive the sculptures on a life-size scale: we can see this effect in Bookmaker, Conversazione, and Malato all’ospedale (Patient at the hospital) – just to name three examples.

Most of the heads that Rosso created have natural dimensions. They present themselves as fragments of a broader reality—much like Degas’ paintings, and in contrast to Rodin’s idea of fragmentation, which ultimately derives from classical sculpture.

In short, I would argue that these photographs show us how Rosso’s sculptures were veritable actors for him, serving as telling protagonists in a theatrical performance of sorts.

In this vein, Rosso’s first photograph (Fig. 18) serves as an exemplar (even though the original has been lost): In front of a drop curtain decorated with the marionettes which he used to improvise plays for children, Rosso placed his sculptures in an apparently random fashion: we can see many versions of the same subject placed in a line, and sculptures of different sizes and dimensions placed near each other. It seems to me that the picture represents a reconstructed street, filled with passers-by. We see Locch (i.e. a young delinquent) twice in the space of a few meters, with slight differences between the two figures. We can also see a male figure (like Cantante a spasso) rendered small by his distance from the camera. Next to him we see a woman (like Ruffiana (A Madam)) poking her head around a large door; contrary to the male figure, she appears to have natural dimensions due to her proximity.

Another example is the photo taken at the Fles residence (Fig. 19) in which Femme à la voilette (Woman with a Veil) looks at Bambina ridente (Laughing Girl) while Malato all’ospedale folds in on himself in the foreground: the three sculptures were captured in a way to transmit the ancient theme of the three ages of man—or of woman.

The same can be said of the photograph that enlarges the juxtaposition of Carne altrui (The Flesh of Others) and Madonna Medici -much like Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love– at the 1904 Salon d’Automne in Paris (Fig. 20).

The only oversized sculpture that Rosso ever created is Ecce Puer (Behold the Boy, Fig. 21) his last work, sculpted in 1906. Through these large dimensions, the sculpture affirms that it is not a portrait of a child, but rather an emblematic image of purity, innocence and truth. It seems to me that the presence of the artist’s worktools in the picture is no accident: they represent the importance Rosso gave to his artistic mission.

Bibliography

Hecker, Sharon. “Medardo Rosso’s first commission.” The Burlington Magazine 138 no. 1125 (December 1996).

Mola, Paola, and Fabio Vittucci, eds. Medardo Rosso: Catalogo ragionato della scultura. Milan: Skira, 2009.

Ogliari Francesco. Milano in Tram. Storia del trasporto pubblico milanese. Milan: Hoepli, 2006.

- For a detailed retracing of the sculpture’s life, see: Sharon Hecker, “Medardo Rosso’s first commission”, The Burlington Magazine, 138 no. 1125 (December 1996): 817-822.

- For more information about Rosso’s sculptures, see : Paola Mola and Fabio Vittucci, Medardo Rosso. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, (Milano: Ed. Skira, 2009), 92-97 and entry I.12, 255-56, with relative bibliography.

- The old houses of Milan, even the more popular ones, all had porter’s lodges. They were usually composed of one sole room next to the main entrance to the building, without any sort of bathroom or latrine. In the poorer complexes, the job of a doorkeeper was executed by single, often elderly, women. who were either widowed or never married off.

- Tramvai were horse-drawn carriages on rails. Approved in 1880 to help support the affluences of people in relation to the 1881 Milan World’s Fair, they were the most economical means of public transportation within the city of Mila.. In contrast to the Omnibus — which did not run on a track— the Tramvai was viewed as an important technological innovation which led to the abolition of animal traction just ten years later. See: Francesco Ogliari, Milano in Tram. Storia del trasporto pubblico milanese. (Milan: Hoepli, 2006), 20-27.

- For more information on the sculpture and photograph, see Mola and Vittucci, Medardo Rosso. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 182-87 e and entry I.34, 320, with relative bibliography.

- Ibid., p. 320.

- Ibid., p. 184

- For information on this lost work, see Mola and Vitucci, 206-09, and entry I.38, 328, with relative bibliography.