Another History: Contemporary Italian Art in America Before 1949

Sergio Cortesini Sergio Cortesini Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/methodologies-of-exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/

This essay looks at modern Italian art circulating in the United States in the interwar period. Prior to the canonization of recent decades of Italy’s artistic scene through MoMA’s 1949 show Twentieth-Century Italian Art, the Carnegie International exhibitions of paintings in Pittsburgh were the premier stage in America for Italian artists seeking the spotlight. Moreover, the Italian government actively sought to promote its own positive image as a patron state in world fairs, and through art gallery exhibitions. Drawing mostly on primary sources, this essay explores how the identity of modern Italian art was negotiated in the critical discourses and in the interplay between Italian and American promoters.

While in Italy much of the criticism boasted a self-assuring “untranslatable” character of national art through the centuries, and was obsessed by the chauvinistic ambition of regaining cultural primacy, especially against the French, the returns for those various artists and patrons who ventured to conquer the American art scene were meager. Rather than successfully affirming the modern Italian school, they remained largely entangled in a shadow zone, between the glaring prestige of French modernism and the glory of the old masters (paradoxically enough, the only Italian “retrospective” approved by MoMA before 1949). Some Italian modernists, such as Amedeo Modigliani, Giorgio de Chirico, and Massimo Campigli, continued to be perceived as French, while the inherent duality and ambiguity in the critical discourse undergirding the Novecento and the more expressionist younger generation – which struggled to conflate Italianism and modernity, traditionalism and vanguardism – made the marketing of an Italian school more difficult. Therefore, despite some temporary critical success and sales, for example for Felice Carena, Ferruccio Ferrazzi, and Felice Casorati, the language of the Italian Novecento was largely “lost in translation.”

Introduction

With the 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, the Museum of Modern Art cast a light on the last four decades of Italy’s artistic scene and embraced it as a prodigal son returned to the kinship of Western modernity. MoMA, as the uppermost artistic institution of the now hegemonic country, normalized cultural relations with Italy, and also winnowed out and reframed the history of modern Italian art that had circulated in the United States before the war. This paper accounts for the prewar vista, in which both American and Italian actors played a part, in a period charged with nationalistic biases, fantasies of renaissance, and anxiety for hegemony.

A thorough scanning of the period between 1900 and 1940 would rake together a wealth of scattered appearances of Italian artworks in private galleries, public venues, local societies, and international exhibitions, along with lists of short articles, reproductions, and collectors. The Julien Levy gallery, opened in New York in 1931, stands out in this landscape as the bridgehead of the Parisian vanguard; through its gate passed works by Giorgio de Chirico, Massimo Campigli, and Leonor Fini. Indeed, de Chirico and Amedeo Modigliani – whose works often appeared in American art magazines alongside scores of Picassos and Matisse’s odalisques – were perceived as Italian stars within the superior Parisian firmament.

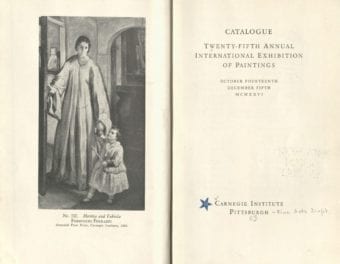

However, piecing together such a broad mosaic would likely prove redundant, since some of the tesserae have already been reconstituted by previous studies.1 I myself recently discussed the challenges assigned by the Italian Fascist government to modern art and architecture in traveling exhibitions and world’s fairs in New Deal America; my references here to those episodes will be minimal.2 The essay that follows will instead focus on lesser-known – and more ephemeral – success stories that for a time bore the standard of Italian identity across the Atlantic. Before MoMA’s 1949 show raised again the curtain on modern Italian art, the Carnegie International exhibitions of paintings were the most illustrious stage on which Italian artists sought the spotlight in America.3 If today the splendor of the Carnegie International is somewhat faded, due to the engulfment of biennials in the globalized art world, and to various interruptions/resumptions and changes in the format, scope, and periodicity of its editions, during the first decades of its history – and especially under the directorship of Homer Saint-Gaudens, who led the institution beginning in 1922 – the annual Carnegie event offered premier surveys of international art, second only to the slightly older Venice Biennale.

More to the point, when industrialist Andrew Carnegie founded the Carnegie Institute’s Department of Fine Arts (now the Carnegie Museum of Art) in 1895, one of his ambitions was to create a public collection of modern art; the series of international exhibitions he established the following year became strategic in this policy of showcasing – and selectively acquiring – what Carnegie called “the Old Masters of Tomorrow.”4 Long before the founding of MoMA in 1929, the Carnegie took upon itself the role of educating its Pittsburgh audience in contemporary art; further, it claimed the status of a national institution in that field, while other public museums and private collectors were mostly interested in established Old Masters. It is thus relevant to consider the early Carnegie shows as a major gateway for the commercial and cultural traffic of Italian art in America, in an epoch predating MoMA’s institutional dominance, and when the latter was still barely receptive to current artistic production in Italy.

Italian Art at the Carnegie

By 1900 only a small cohort of internationally renowned Italian painters had made their way into the American art market; they embodied the viability of the contemporary Italian scene. A handful of Venetian painters – the aging Ettore Tito (born 1859), the slightly younger Italico Brass, and the siblings Emma and Beppe Ciardi (born in the 1870s) – charmed their cosmopolitan American clientele with canvases “painted with a foil,” capturing the light and life of Venetian streets and canals, whether contemporary or recalled from the eighteenth century, along with landscapes, portraits, and even mythological figures.5 The Roman Antonio Mancini (born 1852) painted “like fireworks,”6 and had enjoyed recognition since the mid-1870s, enchanting wealthy patrons with Roman/Neapolitan urchins and peasants. His brushwork, especially late into his oeuvre, involved overworked impasto to highly tactile effect, while blurring forms to create a sense of visual flickering over the pictorial plane. “The colour is beautiful and technique épatante,”7 assured collector and dealer Ralph Curtis to Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1884, as he was commissioning, on her behalf, Mancini’s Il ciociaretto porta stendardo alla festa della mietitura (The Standard Bearer of the Harvest Festival, 1884; figure 1), of an adolescent celebrating the harvest in a religious procession in the Roman Campagna. In 1895, this time at the suggestion of artist John Singer Sargent, Gardner again commissioned a work from Mancini: a seated portrait of her husband, John L. Gardner. Other collectors, including American painter William Merritt Chase, were attracted to Mancini’s work, and in 1892 Ragazzo del circo (A Circus Boy, 1872), a picture based on a juggler seen in Naples, on being presented to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York became the first work by Mancini to enter a public collection anywhere.8

The Italians named above contributed to the annual exhibitions staged as the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, prompting the circulation of their works in additional American cities, including Cleveland, San Francisco, Brooklyn, and Toledo. From the first International curated by Homer Saint-Gaudens in 1923, until the war year 1940, the inclusion of Italian artists grew more prominent.9 Saint-Gaudens availed himself of a network of European representatives, including Ilario Neri in Italy, who assisted in scouting promising works and accompanied him in yearly studio visits; he also instituted the display of works by country, implicitly following the nation-based survey model of the Venice Biennale. Moreover, considering that the United States lacked a federal department of culture, unlike many European countries, Saint-Gaudens considered the Carnegie to have a de facto role in the matter of educating the public in contemporary art – although the International rarely welcomed more daring avant-garde works. He was committed to spreading European art in America and was persuaded of the necessity to broaden the vision of modern art beyond Paris. He was particularly attentive to the Italian art scene because it looked, to him, untainted by the subjectivist extravaganzas of the avant-garde. (“Modern Italian art is neither Cubistic nor Crazy,” he wrote in 1924).10

Saint-Gaudens orchestrated the Italian section to present both “conservative” and “advanced” artists, as he named them. Even though generally the conservatives outnumbered the moderns – and the Carnegie advisory board requested that no aesthetically “radical” artists infiltrate the selection (neither Futurists nor abstract artists were invited) – the show aspired to be equitably representative of the actual current scene. Saint-Gaudens consistently considered Mancini, until his death in 1930, to be an outstanding artist and indispensable champion of the old school, and he exhibited Tito until the end of the decade. (This echoed late career tributes to these masters through solo shows at the Venice Biennale and their appointments to the Accademia d’Italia.)

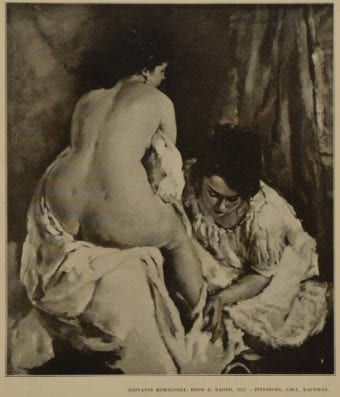

However, in 1924 Saint-Gaudens “discovered” two new artists who, in his mind, embodied the “medium” and “advanced” trends. The first was Giovanni Romagnoli, from Bologna, who at his debut in 1924 won the second prize; he was the first Italian ever to receive the award, for Dopo il bagno (After the Bath, 1922; figure 2), a painting of a broad feminine back turned to the observer, which Saint-Gaudens praised for its “vitality and brilliance.”11 The work was purchased by Edgard J. Kaufmann, Pittsburgh department store owner (and, later, client of Frank Lloyd Wright, for the architectural masterpiece Fallingwater), who lent it for an indefinite time period to the Department of Fine Arts.12 From then on, Romagnoli was regularly invited to participate in the Carnegie International, and he took part in the jury in 1926; he also had a solo show in Pittsburgh and received portrait commissions locally and in New York, taught in 1926 and 1930 at the Pittsburgh Technical School, and in 1940 was commissioned for a fresco to adorn the Italian room of the Cathedral of Learning at Pittsburgh University.13

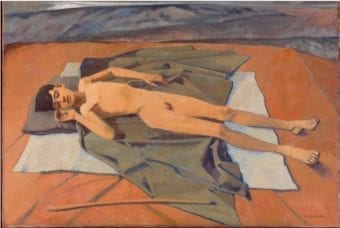

Romagnoli, a delicate, fluffy colorist, represents a strain of traditionalist, softly erotic painting replete with reclining nudes, Venuses, and women captured in the intimacy of their toilettes – in other words, objectified by the male gaze (figure 3). The other “nut” picked by Saint-Gaudens in his scouting trip in 1924 was Felice Casorati, a painter who used iconographic motifs at times similar to Romagnoli’s – including nude women and still lifes – but treated them as accoutrements for self-referential interplays of pictorial planes, colors, and spatial ambiguities devoid of narrative content. Saint-Gaudens described him as “mildly ‘wild’”14 in selecting Casorati’s iconic pseudo-portrait Silvana Cenni (1922), a quintessential work of his blend of neo-Quattrocento and metapictorial references. Casorati later became a modern pillar of the Carnegie shows, and exhibited twenty-five works over twelve editions, from 1924 to 1939; he sat on the jury in 1927, and was awarded the second prize in 1937, for Donna vicino al tavolo (Woman Near a Table, 1936; figure 4).

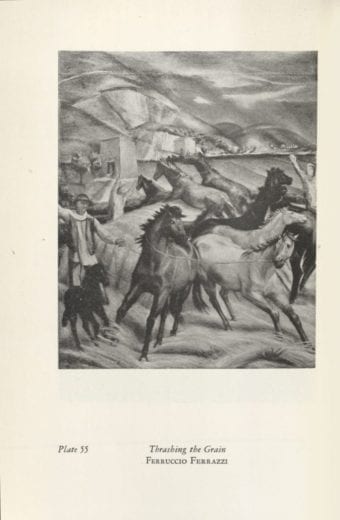

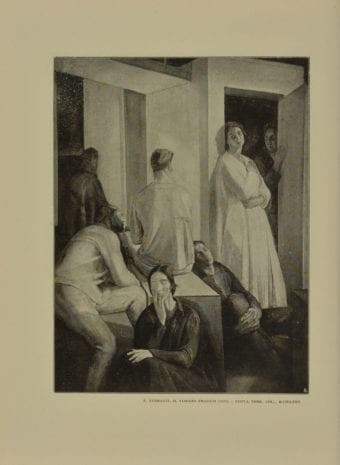

Other pillars of the “advanced” school were Ferruccio Ferrazzi and Felice Carena. Ferrazzi, in 1925, sent Visione prismatica (Prismatic Vision, 1924; figure 5) – an esoteric family portrait typical of his self-indulgent tendency to transfigure everyday gestures into mysterious rituals and settings. Here, the scene pivots around a prism, ostensibly held by the artist, shown to his baby daughter coming out of a bathtub. Ferrazzi was the first Italian to receive, in 1926, the Carnegie’s first prize, for Orizia e Fabiola (Horitia and Fabiola, 1926; figure 6), another remodeling of familiar figures (his wife and daughter) as well as space, through dramatic lighting and angularities; the painting was purchased by W. S. Stimmel of Pittsburgh. Until the end of the 1930s, Ferrazzi exhibited at almost every edition of the Carnegie (with the exception of 1929) his signature repertory of archaic rural scenes (in 1931 he was praised for a Roman countryside, La trita del grano [Thrashing of the Grain, 1928; figure 7]) and esoteric narratives wherein both portraiture and landscape are transfigured into an immemorial age (conveyed also by his revival of encaustic, a medium of the ancient Romans).

Certainly, the Carnegie International succeeded in fostering the visibility of Italian art. In 1924 (the first edition for which Neri served as an agent of the Carnegie) the exhibition was still heavily unbalanced in favor of American artists (with 130 paintings) and also British and French (with sixty pictures representing each nation); only seventeen works were included in the Italian section. The ratio progressively changed to a milder discrepancy: in 1935, one hundred paintings by Americans hung next to fifty each for Great Britain and France, and thirty-four for Italy. The percentage of sales rose from 7% in 1923, to an average of 13% in subsequent years. Carena, in 1929, won first prize for the large painting La scuola (The School, 1928; figure 8); as an homage to Gustave Courbet’s Atelier (1854–55) in Cézannesque brushwork, it represents the red-haired artist himself as a teacher surrounded by pupils at a figure drawing class in Florence’s Accademia di Belle Arti. It was purchased and lent to the Carnegie Department of Fine Arts by industrialist Albert C. Lehman, a self-professed enthusiast of Italian art and Benito Mussolini (with whom he managed to have an interview in the spring of 1930, when he was visiting Rome). Other pictures by Casorati entered public collections, such as the beautiful Icaro (Icarus, 1936; figure 9), bought by the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1938, while the Italians Ubaldo Oppi, Giuseppe Montanari, and Alessandro Pomi, among others, won prizes and attracted buyers.

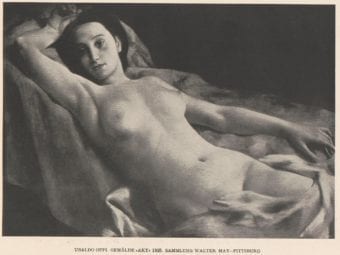

Over the years, the Carnegie followed evolving trends in Italian art, from the “magical realism” typical of the early Novecento (I am referring here to the postvanguard, neoclassicist style of the original group of seven Milan-based painters, gathered under the critical helm of Margherita Sarfatti in 1923)15 to the more expressionist turn of the mid-1930s. In 1925, Saint-Gaudens selected Nudo (Nude, c. 1925; figure 10) by Oppi, another “leader of the young Italian school;”16 the painting is one in a series elaborating on a French album of slightly erotic photographs presented as études académiques for artists, wherein Oppi indulged in the limbo between artificiality and the animation of real life – typical of magical realism. The picture earned him second prize and was bought by local businessman Walter A. May. In 1926, Saint-Gaudens became enthusiastic for two other exponents of Novecento: Piero Marussig, for Signora in blu (Lady in Blue, 1921), and Arturo Tosi, a painter of familiar Lombard landscapes “in which the modern yeast has not oversoured the dough of beauty.”17

In March 1926, Saint-Gaudens visited the landmark first exhibition of Novecento Italiano at Milan’s Palazzo della Permanente, accompanied by Tosi and Neri. (By this time the original kernel of seven vanguard-turned-neoclassicist painters from 1923 had evolved into a looser, larger group, encompassing heterogeneous personal variations over a generally dominant naturalistic and archaizing idiom.) In January 1927, the movement’s leading artists – Tosi, Alberto Salietti, Marussig, Achille Funi, Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, and Ardengo Soffici – bolstered by the success of the Italian section at the previous Carnegie, took direct initiative, writing as a group to ask Saint-Gaudens to consider them as the unique Italian contingent in the upcoming exhibition.18 If their letter confirms the bold attempts of the Novecento to act as a semiofficial movement that could claim to be nationally representative and to boast political backing (Mussolini had attended the openings of the inaugural Novecento shows),19 Saint-Gaudens’s polite refusal in response attests his ability to navigate a narrow path between cooperating with Italian advisors and cultural officials and remaining faithful to his mission to present as wide as possible a survey of “advanced” and “conservative” artists.

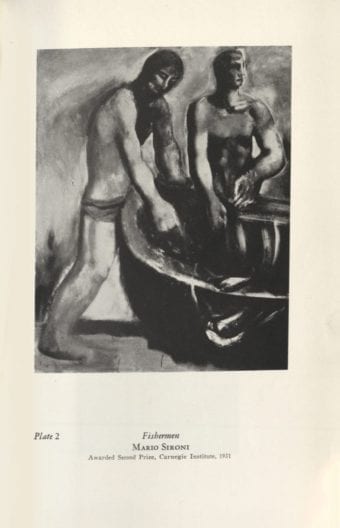

Saint-Gaudens’s typically moderate taste adapted itself to evolving trends. In the late 1920s, he considered Sironi and Carrà too crude in their expressionist distortions. However, Neri, despite his personal disapproval of Sironi’s coarse style (“Certainly, I think, nobody would like to have a portrait made by him!”),20 in 1931 had to admit, in a letter to Saint-Gaudens, that his works were “strong and important […] modern, interesting, and original.”21 Saint-Gaudens did invite the artist in acknowledgment of his role as a trendsetter, and Pescatori (Fishermen, c. 1930; figure 11) was awarded second prize. The picture, as one reviewer put it, left “critics as well as laymen […] distraught” for its “crudity,” while its “architectural strength” and “a sense of the elemental salt-wash and weather of the sea in its line and color […] cannot easily be put into words.”22 Sironi and Carrà, along with Giorgio Morandi, Casorati, and Carena, became the new protagonists of the Carnegie, while Oppi was left out, considered artistically exhausted.

In choosing the artists to invite every year, Saint-Gaudens had only dim insight into – or interest in – the current debate and factions then dividing art criticism in Italy. He seems to have been oblivious of the feud opposing admirers of Sironi’s expressionist style and traditionalists over the issue of genuinely Italian – and orthodox Fascist – art prompted by the revival of mural painting in 1933, nor does he seem to acknowledge the harsh polemic about “sound” (classicist in style, nationalist in subjects) versus “degenerate” (expressionist and allegedly un-Italian) art toward the end of the decade. His approach was more instinctual, based on his personal taste, defined by an innate conservatism that slowly acclimatized to incipient modernist innovations. He relied on Neri’s and other acquaintances’ counseling, had a sense of evolving trends through the catalogues of the Venice Biennale and the Quadriennale in Rome, but he never fully mixed with Italian factionalism and politicization.

A case in point is his attitude vis-à-vis Corrado Cagli. In 1936, Cagli, then twenty-six years old, was the rising star of the younger Roman School. His loose brushstrokes and light palette set him apart from the naturalism and somewhat frigid archaism of Novecento painters. Saint-Gaudens’s first meeting with him in Rome was less than sympathetic:

Nothing less than a Principessa or a Contessa telephoned me. They knew that our show was run between a slice of lemon and sugar in the tea. Moreover, teacups run to Cagli, and Cagli will reform Italian art first and all modern art later. I investigated. I had a dreadful time sorting Cagli out of a litter of cats, babies, garlic, and vegetable ullage. At half past ten in the morning I rang his bell. At a quarter to eleven he appeared in pyjamas; a dark young man with quivering stained fingers, who lived […] in the midst of the most extraordinary pictorial nightmares that have yet assailed my hard-boiled nerves. I hate to believe that Cagli is the Messiah of Art.23

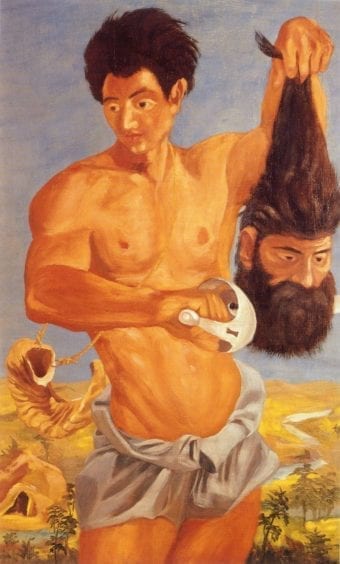

However, the following year, shifting from sarcasm to pragmatic irony, Saint-Gaudens included Cagli’s Davide e Golia (David and Goliath, 1937; figure 12). “Do not blush,” he wrote to Neri. “We are in need of a little excitement, and the young idea keeps calling ‘Cagli!’ to me. So I took the plunge.”24 And in 1938, in a Life magazine article, Saint-Gaudens went so far as to single out Cagli as one of “tomorrow’s masters.”25

Italian Cultural Politics Beyond the Carnegie International

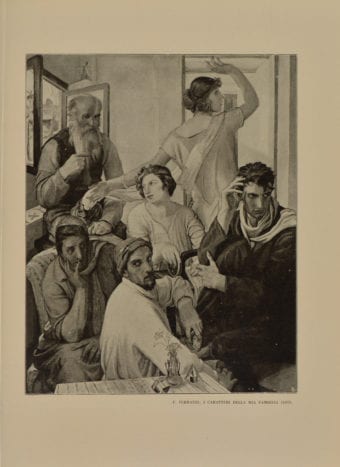

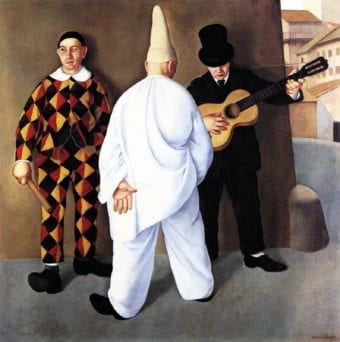

Despite his personal admiration for the sociopolitical actions of the Fascist regime, and his judgment that contemporary art in Italy expressed, in a lively manner, its society, Saint-Gaudens remained an idealistic self-appointed arbiter of taste for the American public. However, although the Carnegie International was a private venture, Saint-Gaudens cooperated with some of the eminences in the Italian art system, including critic Ugo Ojetti; painter and politician Cipriano Efisio Oppo; and Arduino Colasanti, Director General of Fine Arts. He also met personally with Mussolini in 1926 and 1931. In the attempt to secure from artists their best recent works, the Carnegie had to coordinate its plans with competing exhibitions – namely, Rome’s Quadriennale and the Venice Biennale – which drained important paintings and offered more substantial prizes. Moreover, it witnessed the increasing autonomous engagement of the Italian government in support of its modern national art on America soil. An early example of this was in 1926, when the Directorate General of Fine Arts of the Ministry of Public Instruction organized a large exhibition at the Grand Central Galleries in New York that attested to an appreciation for Casorati, Ferrazzi, and Antonio Donghi, among others. Ferrazzi exhibited Caratteri della mia famiglia (Characters of My Family, 1923; figure 13), a mannered staging of his relatives acting out various attitudes, and Viaggio tragico (The Tragic Journey, 1923; figure 14); both were purchased by the New York collector Carl Hamilton, who in the following year also bought Donghi’s Carnevale (Carnival, 1924; figure 15), awarded an honorable mention at the Carnegie. These were contemporary additions to Hamilton’s splendid collection, already famous for its Italian Renaissance selection (including works by Masaccio and Piero della Francesca).

Prior to 1930, Margherita Sarfatti had enjoyed sufficient political influence to streamline the Novecento Italiano as a quasi-official national art movement steered by a directive board tasked with an ambitious program of cultural expansion through exhibitions across European capitals and as far away as Argentina and Uruguay. However, with the decline of Sarfatti’s political star, Oppo rose as the new homme-orchestre of the art system. As of 1930, when he was appointed Secretary General of the Quadriennale, he took the lead pursuing a more proactive policy in promoting the commercial success of Italian art abroad and its potential in fostering the national image. In 1931, he maneuvered adroitly to secure, through the cooperation of Roland McKinney at the Baltimore Museum of Art, the exhibition of a large selection from the Quadriennale in Baltimore, and these works subsequently traveled to Syracuse, New York; Boston; and Washington, D.C. He also managed to send works to Birmingham, Alabama. Moreover, he allowed the loan of pictures from the Quadriennale to the Carnegie, and personally arrived in Pittsburgh to sit on the jury (he would take credit for the prize to Sironi).26

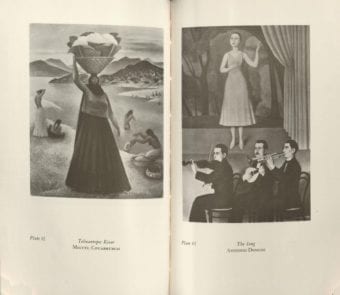

By the mid-1930s, more actors had joined the composite strategy of cultural trafficking. In 1935–36, an exhibition of ninety pictures curated by former gallerist and critic Dario Sabatello toured twelve cities across the U.S., and in 1938, Comet Gallery – patronized by Countess Anna Laetitia Pecci Blunt – ran a season of Italian art exhibitions in New York. Both Sabatello and Pecci Blunt promoted especially the younger generation headed by Cagli and his fellow painters of the so-called Roman School, who ventured into elusive narratives and archaic-looking landscapes picturing evanescent forms with expressionistic brushstrokes and softly hued colors; just like their Novecento older fellows, they avoided explicit political themes, but provided fresher alternatives to the overused reclining nudes, Susanna and the Elders, and the like. In 1939, the Italian government resolutely played the card of art’s power by sending to the San Francisco World’s Fair some thirty masters of the Renaissance along with forty contemporary paintings and sculptures, plus several drawings; the selection, which included works by Morandi, Scipione, and Filippo de Pisis, outnumbered the initial request of the American organizers (figure 16).27

Saint-Gaudens’s personal taste can perhaps be best ascertained from his private correspondence with Neri and the Committee of Fine Arts at the Carnegie. The critical apparatus of the catalogues of the Carnegie is meager, and their texts merely informative and circumstantial. As a result, the Carnegie remained an exhibition aimed at offering synthetic, nonpartisan, unpolitical surveys based on visual qualities, where both modern (but not “radically” so) and conservative tendencies were displayed to the public. In 1927, the Committee of Fine Arts advised against publishing an interview with Mussolini as a foreword to the Italian section, because it would introduce a political element. In the hanging of the rooms, the intention was that visitors compare the variety of options seen next to one other – the mix of styles and generations, the purist Donghi next to the overcharged Mancini, for instance (figure 17). Also, the illustrations in the catalogues offer didactics based essentially on analogy, matching artists of different nationalities but comparable for echoing iconographies or compositional schemes (figure 18). The accompanying publications managed directly by Italians were equally lacking in loquaciousness (with the exception of Sabatello’s foreword to the catalogue of the traveling exhibition in 1935–36); even so, in comparison with the rather instinctual, adaptive, and pragmatic curatorial choices made by Saint-Gaudens, the Italian curators backed the artworks with a more opinionated cultural agenda.

From the Italian point of view, the Carnegie and the other events or venues directly run by Italians were outposts in a four-point campaign: to proselytize the alleged national identity in modern art; to conquer the spotlight against the critical and commercial monopoly of the School of Paris; to restore Italy as a cultural world power; and to angelize its Fascist regime. Yet for all the stylistic developments over nearly two decades – from the heightened plasticity of the Novecento in the early 1920s to the looser expressionist forms of the late 1930s – the discourse around Italian art changed little, and conformed to the script of a grand historical drama. This indicated a move from decadence to regained vigor, from passivity and cultural colonization under the French heel to new grandeur and hegemony.

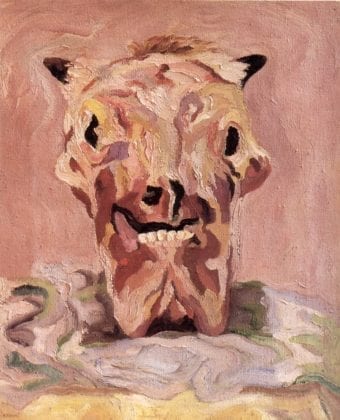

From Sarfatti’s early writings on the Novecento, to her Storia della pittura moderna (History of Modern Painting, 1930), to Sabatello’s foreword in 1935, to Pecci Blunt’s catalogue preface28 and speeches for the opening of the Comet Galley, and so on, the standard discourse revolved around the same obsessions. These were the historical and cultural categories of “Latin” and “Mediterranean” – played against “Nordic” and “Protestant” – with stylistic corollaries of “plasticity” and “architecture” within paintings. The predictable target was the nineteenth century, when Italy’s artistic prestige was eclipsed by French Realism and Impressionism, which, however, had ultimately debased the artistic imagination to anecdotal and descriptive trivia. Counter to this, postvanguard Italian art had regained “the spiritual directives at the roots of our culture” – as Sabatello put it – that is, the sense of synthesis, measure and balance, and well-defined structures.29 Even when these characteristics were, in fact, hardly visible – such as in the pictorial handling of Cagli, Scipione, or Carlo Levi (figure 19) – their quasi-surrealist or expressionist transfigurations were discursively reframed as the resurgence of humanism and of the historical drive for “good painting,” which preferred subtle tonalities to violent color, and harkened back to the palette and frail figures of Pompeian frescoes.

The obsession against French dominance betrays the inferiority complex and revanchism of a country that refused to admit its art had lost its pivotal position in Western culture. The very anxiety and claim for the lost primato summons up the phantom of the Renaissance, but this self-assuring relation with the glorious past was a Holy Grail as much as it was a burden. I would argue that it proved impossible for both Italian and American viewers to do away with the meter of this myth. Saint-Gaudens often peppered his diary of studio visits in Italy with considerations of the social meaningfulness of art during the Renaissance, at odds with the materialism and lack of taste in his own Pittsburgh. He considered the Renaissance to have been the historical period that set the standards of art – an age of “nearly universal consensus of opinion on the part of a social order concerning the rules and regulations which bounded what gave that order visual delight.”30 He believed that contemporary Italian art was the living expression of a national society now spiritually rejuvenated and strengthened by Fascism, in contrast to Nazi Germany, where art was artificially Aryanized. And yet, for all his esteem for Italian painting, he could not help musing about stereotypical discourses – the paragon of the Renaissance and the vulgarity of America:

How do we dare talk art to an Italian, we whose sense of beauty must be as attractive to them as their losanges [sic] of garlic are to us? What do we know about civilization just because we can screw more bolts on the bottom of a Ford in one minute than any other race on earth? Venice for six hundred years fought and reveled and traded and produced, carried on by a surge of the emotions that still echoes through that old square, and we for one hundred and fifty years have grown fat upon the crudities of nature, and I come over here to pat the Italians on the back. Oh shut up!31

American critics often returned to the Renaissance in reviewing various Italian artists, whether to praise or attack them. “It’s a dismal little Renaissance. This art, we are told, is one of the elements ‘bearing witness to the rebirth of a people.’ Judging from it, they must have used plenty of chloroform,” wrote a New York Post critic in 1935, in a review of the apparently dull figures of the Roman School in Sabatello’s show.32 On the other hand, an enthusiastic Arthur Millier noted, in the Los Angeles Times, that Italian art had broken the chain of a long decadence to reemerge strong, Mediterranean, and modern, and he praised the overpowering masterpieces of Sironi as those of a new Michelangelo.33 Not surprisingly, when the show stopped at the Seattle Art Museum, an exhibition of facsimile pictures by Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, and other Quattrocento masters was hung next to it.

The Italian critics’ discursive rhetoric explained contemporary art as a move from degeneration to the recovery of Italian selfhood, and it was not simply constructed as rebirth. The rhetoric obeyed a more complicated and paradoxical teleology, one that rationalized history as moving forward while seeking eternity. Sarfatti’s conferences reiterated the concept of an evolution from the modern to the eternal. If her dialectical acrobatics – which saluted “Italian, traditionalist, modern” artists, willing to “halt in time some novel aspect of tradition”34– served as a mantra of the domestic discourse, the self-assuring intraducibilità (untranslatability), as she put it, of Italian artistic expression over the centuries was, in fact, lost in translation in America.

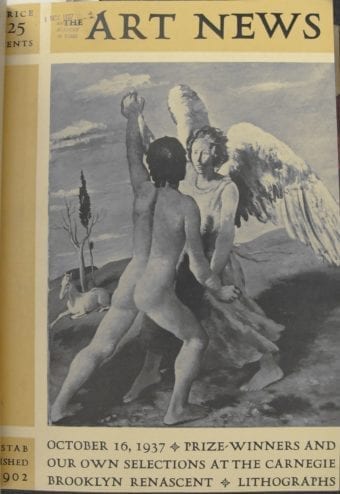

Despite some noteworthy evidence of success – the number of sales, an Art News cover dedicated to Carena (1935 ca; figure 20), and a mention of a Casorati as the only Italian amid the all-French roster of notable paintings in the market35 – Italian artists remained largely entangled in the shadows, between the glaring prestige of French modernism and their own national past. The task of showing their modern artistic face was Sisyphean. In the major art magazines of the period, the coverage of French artists was comparable only to that of shows and sales of Renaissance works, and the Italian moderns appeared only rarely (with the exception of the Modigliani–de Chirico duo, bien sûr). Paradoxically enough, the only Italian “retrospective” sponsored by MoMA before the war was the greatly acclaimed Italian Masters, in 1940: thirty Renaissance artworks shipped from Italy (and already lent to the San Francisco Word’s Fair and the Art Institute of Chicago). Alfred H. Barr, Jr., accepted them as a source for modernism, but kept MoMA impenetrable to the Italian government’s attempt to slate a show of contemporary art. Instead, he mounted the parallel exhibition Modern Masters from European and American Collections – not one master was Italian.

Conclusion

In 1949, Twentieth-Century Italian Art did include some artists who had already appeared at the Carnegie International and other shows before the war. By putting more emphasis on their formal qualities, the exhibition lifted the spell of pompous nationalist rhetoric to recast them in a progressive narrative that set the beginning of modern art in Futurism, and schematized from there onward a chain of subsequent movements: Metafisica, followed by the reactionary Novecento, then the counter reactions of the Roman School, Corrente, and, finally, the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti (New Front of the Arts).

If we consider retrospectively the three approaches to Italian art, we find three models of temporality. Barr and Soby’s evolutionary scheme subverted the synoptic vision pursued by Saint-Gaudens. On the other hand, they disrupted the Italians’ ideological mobilization of the past and their temporality, which unfurled and returned to itself as a pendulum, only to reach alleged ultimate “eternal” values. The MoMA show, along with the contemporaneous establishment of the Greenbergian canon of a diachronic trajectory culminating in abstraction, led to the downplaying of Novecento. In 1949, the museum left out not only the older Tito and Brass but also the more traditionalist Carena and Romagnoli, and the idiosyncratic Ferrazzi, while Casorati was downsized to the rank of exponent of the Turin School.

The didactic criterion chosen by Saint-Gaudens in the old days of the Carnegie was later echoed on a vast and comprehensive scale in another landmark exhibition, L’arte moderna in Italia 1915–1935 (Modern Art in Italy, 1915–1935), curated by Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti in Florence in 1967. Here, virtually all the significant artists once active in the Italian system were purportedly presented “objectively,” nonjudgmentally and free of historicist/teleological schema, for the contemplation of viewers. Based on the assumption that the act of looking at artworks revives the cognitive process of the artist’s original look onto the world, and that any true work of art opens the humane “poetry” of its creator, Ragghianti shunned any other benchmark (ideological, political, cultural) as dogmatic and conformist pseudoconcepts.36 Adamantly defending the tenet that a work of art is the “concrete thought” of any given artist, that is the visual configuration of his/her spiritual life, the exhibition was a belated bulwark of idealism based on Benedetto Croce’s and Konrad Fiedler’s aesthetic theories, and it was unyielding to the contemporaneous dawn of poststructuralism. Yet, despite its idealist dream of the “universal” poetry flowing out the solitary work of any true artist, Ragghianti’s enterprise can also be considered as a pioneering postmodernist remapping avant la lettre. Meanwhile, in the U.S. many of the Carenas, Donghis, Ferrazzis, and Casoratis had fallen into critical oblivion, and were being deaccessioned by museums and private collections.

The Carnegie Museum of Art has sold the majority of the pictures that marked the success of the Italian section. In 1957, it deaccessioned Casorati’s Colline (Hills), purchased in 1931 directly from the painter. Felice Carena’s The Studio, given to the museum in 1938 by Mrs. Albert Lehman, and Meriggio (Midday in Summer, 1934), exhibited in 1936 and purchased in 1937, were both deaccessioned in 1978. (The Studio is now in the collection of Monte dei Paschi di Siena.) Ferrazzi’s The Tragic Journey, purchased in 1939 from dealer and Old Masters expert Julius Weitzner, was auctioned in 1978 (it is now in a private collection in Rome). Romagnoli’s Dopo il bagno remained at the museum on indefinite loan from Kaufmann until 1950, when it was formally accessioned, only to be sold in 1978. Two paintings by Mancini, Ritratto in rosso (Portrait in Red, undated, ca 1920 and possibly retouched in 1926) and Conchiglie (The Shells, 1925; figure 21), both exhibited at the 1926 Carnegie International and bought for the permanent collection, were deaccessioned in 1965 and 1966.

Casorati’s Woman Near a Table, honored at the 1937 Carnegie, purchased by collectors Earle and Mary Ludgin, and later donated to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, was deaccessioned in 2006 (now it is in the collection of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna). Carrà’s Dopo il bagno (After the Bath, 1931; figure 22) was exhibited in Los Angeles in 1935, within the show curated by Sabatello. It caused a fuss over “degenerate art” when it was purchased by philanthropist Preston Harrison and given to the Museum of History, Science and Art in Los Angeles (now the Los Angeles County Museum of Art) as the first item of a prospective gallery of modern Italian art, to be established next to French and American galleries; Dopo il bagno was sold in 1977.37

Most of these pictures (and the list may continue) have returned to Italian hands, to their original market. They were dusted off, as of the postmodernist 1980s, with the scholarly rediscovery of the interwar period, which took its lead from Ragghianti’s unique and wide-angled perspective. The MoMA exhibition of 1949 played a major role in writing the modernist narrative of Italian art in America. The show offered Barr the chance of conspicuous acquisitions for the permanent collection of historic Futurist masterpieces by Carlo Carrà, Gino Severini, Umberto Boccioni, and Giacomo Balla, along with a group of post-World War II emerging artists who were then reviving modernist idioms (particularly Renato Guttuso). The acquisition policy instead overlooked the interwar period.38 In the long run, however, the perspective of Saint-Gaudens – one that implicitly privileged the criterion of contemporaneous art over modern art, and banned Italian Futurists of any generation from his selections – reveals more affinities with the posthistoricist revisions triggered by Ragghianti. He dared – unconventionally enough in 1967 – to set the starting point of his gigantic, panoptic, non-evolving survey of Italian “modern” art in 1915, when the virtual demise of the first wave of Futurism occurred. Ragghianti dismissed Marinetti’s movement as overrated and as merely an historicist myth, thus affirming – analogously, if unintentionally, to what Saint-Gaudens had done – the value of contemporaneity over modernistic ideology, and suggesting the possibility of a different, antimodernist, politically aseptic modernity.

Bibliography

Anthology of Contemporary Italian Painting. New York and Rome: Cometa art Gallery, 1937.

Barisoni, Elisabetta. Viaggio alle fonti dell’arte. Il moderno e l’eterno Margherita Sarfatti 1919–1939. Treviso: ZeL Edizioni, 2018.

Bedarida, Raffaele. Corrado Cagli. La pittura, l’esilio, l’America (1938–1947). Rome: Donzelli, 2018.

Braun, Emily. Giorgio de Chirico and America. New York: Hunter College of the City University; Rome: Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico; Turin: Allemandi, 1996.

“Buys Italian Painting.” Art Digest 9, no. 16 (May 15, 1935): 10.

Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti e l’arte in Italia tra le due guerre. Nuove ricerche intorno e a partire dalla mostra del 1967 ‘Arte moderna in Italia 1915–1935,’ edited by Paolo Bolpagni and Mattia Patti. Lucca: Edizioni Fondazione Ragghianti Studi sull’arte, 2020 (forthcoming 2020).

Catalogue Twenty-fourth Annual International Exhibition of Paintings. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute Press, 1925.

Cortesini, Sergio. “Invisible Canvases: Italian Painters and Fascist Myths across the American Scene.” American Art 25, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 52–73.

Cortesini, Sergio. “Casorati negli Stati Uniti.” In Felice Casorati. Collezioni e mostre tra Europa e Americhe, edited by Giorgina Bertolino, 47–63. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2014.

Cortesini, Sergio. “La Italian Art Exhibit di Birmigham (AL) del 1931: arte italiana, ascesa sociale, progetti civici nel profondo Sud americano.” L’uomo nero, nos. 11–12 (May 2015): 105–25.

Cortesini, Sergio. One day we must meet. Le sfide dell’architettura e dell’arte italiane in America 1933–1941. Monza: Johan and Levi, 2018.

Cortissoz, Royal. “The International at Pittsburgh, Prevailing Currents in European Paintings.” New York Herald Tribune, May 4, 1924.

Defries, Amelia. “Italico Brass, the Canaletto of Our Time.” The American Magazine of Art 14 (November 1923): 608–12.

Exhibition of Contemporary Italian Painting, under the Auspices of the Western Art Museum Association and the “Direzione Generale Italiani all’Estero.” Tivoli: Officine grafiche, 1934.

Giovanni Romagnoli. L’eterna giovinezza del colore 1893–1976. Bentivoglio: Grafiche dell’Artiere, 2014.

Hiesinger, Ulrich W. Antonio Mancini. Nineteenth-Century Italian Master. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2007.

“Homer St.-Gaudens Runs Great Carnegie Show.” Life (December 12, 1938): 72.

Imbellone, Alessandra. Il Novecento di Ferruccio Ferrazzi (1891–1978). Rome: Berardi Galleria d’Arte, 2019.

Lipparini, Giovanni. “Il pittore Giovanni Romagnoli.” Dedalo, year 6, vol. 1, no. 3 (1925–26): 183–201.

Millier, Arthur. “Mussolini’s Sponsorship of Art Shows Striking Results.” Los Angeles Times, February 24, 1935.

“Museum Purchases Modern Italian Works From 20th-Century Italian Art Exhibition,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, press release available at this link (last accessed November 10, 2019).

“New Fascist Art Dismal and Inert.” New York Post, March 21, 1936.

“Notable Paintings in the Art Market. Part II: Modern European Masters.” Art News 36, no. 13 (December 25, 1937): 10–13.

Powell, Mary. “The Foreign Section of the Carnegie International Exhibition.” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 17, no. 2 (April 1932): 25.

Sarfatti, Margherita. Storia della pittura moderna. Rome: Cremonese, 1930.

Solmi, Franco. Giovanni Romagnoli. Bologna: Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna, 1981.

Virno, Cinzia. Antonio Mancini. Catalogo ragionato dell’opera. Rome: De Luca editori d’arte, 2019.

Archival Sources

Neri, Ilario. Letter to Homer Saint-Gaudens, June 7, 1924. Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C., Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art Records, 1883–1962 [hereafter: Carnegie records], box 100, “Neri Ilario 1924” folder.

Neri, Ilario. Letter to Homer Saint-Gaudens, January 13, 1927. Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri Ilario Jan–May 1927” folder.

Neri, Italo. Letter to Homer Saint-Gaudens, July 10, 1931. Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri 1931” folder.

Neri, Italo. Letter to Homer Saint-Gaudens, October 6, 1931. Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri 1931” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to Edward D. Balken, December 8, 1923. Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee – 1923” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to Edward D. Balken, April 1, 1926. Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee – 1926” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to Edward D. Balken, April 4, 1926. Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee – 1926” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to Ilario Neri, January 31, 1927. Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri Ilario Jan–May 1927” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. “Paintings Recommended for Purchase.” Carnegie records, box 101, “Fine Arts Co, May–Dec 1929” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to George E. Shaw, May 13, 1933. Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee Jan–May 1933” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to John O’Connor, April 15, 1936. Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee, 1935” folder.

Saint-Gaudens, Homer. Letter to John O’Connor, March 30, 1937. Carnegie records, box 161, “January–October 1937” folder.

How to cite

Sergio Cortesini, “Another History: Contemporary Italian Art in America Before 1949,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/another-history-contemporary-italian-art-in-america-before-1949/, accessed [insert date].

- An outstanding example is Emily Braun, Giorgio de Chirico and America (New York: Hunter College of the City University of New York; Rome: Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico; Turin: Allemandi, 1996). For Felice Casorati’s market and critical success in the United States, see Sergio Cortesini, “Casorati negli Stati Uniti,” in Felice Casorati. Collezioni e mostre tra Europa e Americhe, ed. Giorgina Bertolino (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2014), 47–63.

- Sergio Cortesini, One day we must meet. Le sfide dell’architettura e dell’arte italiane in America 1933–1941 (Monza: Johan and Levi, 2018).

- All the uncredited information concerning the Carnegie international prize is drawn from the Archives of American Art, Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art Records, 1883–1962 (hereafter: Carnegie records), box 100, “Neri Ilario 1923” folder, and box 101, “Neri Ilario 1940” folder.

- Ingrid Schaffner and Liz Park, Carnegie International, 57th Edition – The Guide (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Museum of Art, 2018), 23.

- Guillaume Lerolle, “European Art,” in Catalogue Twenty-fourth Annual International Exhibition of Paintings, (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute Press, 1925), unpaginated.

- Ibid.

- Ralph W. Curtis, letter to Isabella Stewart Gardner with sketch of Antonio Mancini’s The Standard Bearer (c. 1884), available at this link (last accessed August 21, 2019). See also Cinzia Virno, Antonio Mancini. Catalogo ragionato dell’opera, vol. 1 (Rome: De Luca editori d’arte, 2019), 240–41.

- For Mancini’s market and exhibitions in America, see Ulrich W. Hiesinger, Antonio Mancini. Nineteenth-Century Italian Master (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2007), 13, 50, 71, 72; and Virno, Antonio Mancini.

- Homer Saint-Gaudens succeeded to John W. Beatty in the post of director of the Department of Fine Arts at the Carnegie Institute late in 1922. The twenty-second International, which opened in April 1923, was the first edition he curated. He maintained his post until 1950.

- Homer Saint-Gaudens, letter to Edward D. Balken, December 8, 1923, Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee 1923” folder.

- Giovanni Lipparini, “Il pittore Giovanni Romagnoli,” Dedalo, year 6, vol. 1, no. 3 (1925–26): 197–98. Saint-Gaudens’ statement is reported in Royal Cortissoz, “The International at Pittsburgh, Prevailing Currents in European Paintings,” New York Herald Tribune, May 4, 1924. For press reviews of Dopo il bagno, see Franco Solmi, Giovanni Romagnoli (Bologna: Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna, 1981), 32–33.

- Ilario Neri, letter to Homer Saint-Gaudens, June 7, 1924, Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri Ilario 1924” folder. Piazzetta San Marco by Tito was purchased by the Carnegie Museum of Art (since deaccessioned).

- For the fresco representing Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Priscopia, commissioned in 1940 but completed in 1949, see Giovanni Romagnoli. L’eterna giovinezza del colore 1893–1976 (Bentivoglio: Grafiche dell’Artiere, 2014), 25–30.

- Homer Saint-Gaudens, letter to Edward D. Balken, December 8, 1923, Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee November–December 1923” folder. On the rise and decline of America’s interest in Casorati, see Cortesini, “Casorati negli Stati Uniti.”

- The group – comprised of Anselmo Bucci, Leonardo Dudreville, Achille Funi, Gian Emilio Malerba, Piero Marussig, Ubaldo Oppi, and Mario Sironi – was officially presented at the exhibition Sette pittori del Novecento italiano (Seven Painters of the Italian Novecento), which opened on March 26, 1923, at Milan’s Pesaro gallery. In attending the opening, Benito Mussolini gave a speech whereby he argued for the social meaningfulness of modern art for the state and the analogy between artistic and political creativity, while maintaining that artistic freedom was a vital necessity.

- Homer Saint-Gaudens, “Paintings Recommended for Purchase,” Carnegie records, box 101, “Fine Arts Co, May–Dec 1929” folder.

- Homer Saint-Gaudens, letter to Edward D. Balken, April 1, 1926, Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee – 1926” folder.

- The visit to the Novecento exhibition and correspondence with the artists is described in letters from Neri to Saint-Gaudens, January 13, 1927, and Saint-Gaudens to Neri, January 31, 1927, Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri Ilario Jan–May 1927” folder.

- See note 15. Mussolini also attended the opening of the Novecento Italiano exhibition in 1926 and gave another speech.

- Neri, letter to Saint-Gaudens, October 6, 1931, Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri 1931” folder. The excerpt continues: “Sironi is really an advanced painter and his work, I think, are valued only in the present moment of confusion in everything and also on account of his friendship with the Premier and Mrs. Sarfatti. […] However, our duty is to show what we are doing here and what is appreciated here [in Italy] […]. Certainly the history of art will never consider him, nor many others like him as a painter of this period.”

- Neri, letter to Saint-Gaudens, July 10, 1931, Carnegie records, box 100, “Neri 1931” folder.

- Mary Powell, “The Foreign Section of the Carnegie International Exhibition,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 17, no. 2 (April 1932): 25.

- Saint-Gaudens, letter to John O’Connor, April 15, 1936, Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee, 1935” folder. Saint-Gaudens was likely alluding to countess Anna Laetitia Pecci Blunt, collector and owner of the Galleria della Cometa. The princess might be Marguerite Caetani di Bassiano, née Marguerite Chapin, American naturalized Italian, who was a publisher, journalist, art collector, and patron; Cagli mentioned her twice in his CV attached to the application for a Guggenheim fellowship in 1939: see Raffaele Bedarida, Corrado Cagli. La pittura, l’esilio, l’America (1938–1947) (Rome: Donzelli, 2018), 78.

- Saint-Gaudens, letter to O’Connor, March 30, 1937, Carnegie records, box 161, “January–October 1937” folder.

- “Homer St.-Gaudens Runs Great Carnegie Show,” Life (December 12, 1938), 72; Saint-Gaudens is also quoted in Bedarida, Corrado Cagli, 65–66.

- On Oppo’s role in transferring sections of the First Quadriennale to Baltimore and Birmingham in 1931, as well as on loans to the Carnegie, see Cortesini, “Casorati negli Stati Uniti,” 51; and Sergio Cortesini, “La Italian Art Exhibit di Birmigham (AL) del 1931: arte italiana, ascesa sociale, progetti civici nel profondo Sud americano,” L’uomo nero, nos. 11–12 (May 2015): 105–25.

- On the Italian participation in the San Francisco World’s Fair, and on the ensuing projects for the promotion of contemporary Italian art, see: Cortesini, One day we must meet, 165–214.

- Anthology of Contemporary Italian Painting (New York and Rome: Cometa Art Gallery, 1937).

- Exhibition of Contemporary Italian Painting, under the Auspices of the Western Art Museum Association and the “Direzione Generale Italiani all’Estero” (Tivoli: Officine grafiche, 1934), 9.

- Saint-Gaudens, letter to George E. Shaw, May 13, 1933, Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts committee Jan–May 1933” folder.

- Saint-Gaudens, letter to Edward D. Balken, April 4, 1926, Carnegie records, box 161, “Fine Arts Committee – 1926” folder.

- “New Fascist Art Dismal and Inert,” New York Post, March 21, 1936.

- Arthur Millier, “Mussolini’s Sponsorship of Art Shows Striking Results,” Los Angeles Times, February 24, 1935.

- Margherita Sarfatti, Storia della pittura moderna (Rome: Cremonese, 1930), 126. On the modern-eternal concept in Sarfatti’s writings, see Elisabetta Barisoni, Viaggio alle fonti dell’arte. Il moderno e l’eterno Margherita Sarfatti 1919–1939 (Treviso: ZeL Edizioni, 2018).

- “Notable Paintings in the Art Market, Part II: Modern European Masters,” Art News 36, no. 13 (December 25, 1937): 10–13.

- For Ragghianti’s formalist and idealistic critical vision undergirding L’arte moderna in Italia 1915–1935, see Sergio Cortesini, “Lo storicismo estetico di Ragghianti e altri miti critici nel 1967,” in Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti e l’arte in Italia tra le due guerre. Nuove ricerche intorno e a partire dalla mostra del 1967 ‘Arte moderna in Italia 1915–1935,’ edited by Paolo Bolpagni and Mattia Patti (Lucca: Edizioni Fondazione Ragghianti Studi sull’arte, 2020), forthcoming.

- “Buys Italian Painting,” Art Digest 9, no. 16 (May 15, 1935): 10.

- “Museum Purchases Modern Italian Works From 20th-Century Italian Art Exhibition,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, press release available at this link (last accessed November 10, 2019).