Fortunato Depero and the Theatre

Günter Berghaus Günter Berghaus Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/depero/

The essay discusses Depero’s Plastic Assemblages as para-theatrical experiments of 1914–1916 and explores the abstract correlations of color, sound and movement in his animated performances. It investigates how Depero developed his concept of polyexpressive artificial beings and how he sought to translate his ideas in 1916–1917 in Il giardino zoologico (The Zoo), Chant du Rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale) and Balli plastici (Plastic Ballets). The second part of the essay focuses on Depero’s work in the 1920s, especially the production of Anihccam del 3000 (Enicham of 3000) and his New York projects of The New Babel.

Fortunato Depero arrived in Rome in December 1913 (figure 1). He was twenty-one years old, penniless, and had been attracted to the capital by the news circulating in his hometown Rovereto about the Futurist renewal of Italian culture. A few months earlier, he had established contacts with the Lacerba group in Florence and begun to orientate his artistic production towards a Futurist aesthetics.1 In Rome, he visited the Boccioni exhibition held at the Galleria Sprovieri and made the acquaintance of Giacomo Balla, who offered him hospitality in his house and soon became his fatherly mentor and friend.2

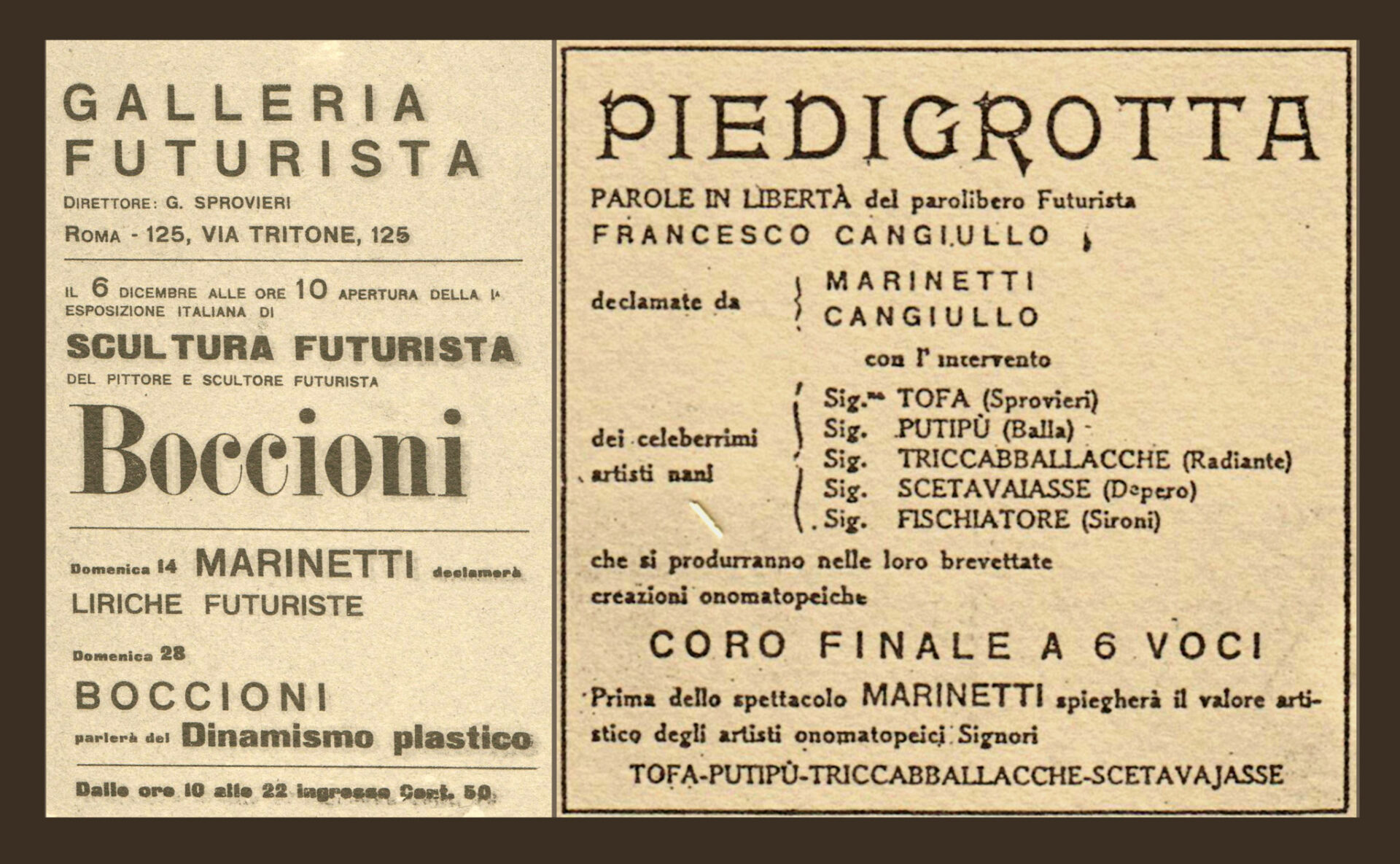

In 1914, Balla introduced Depero to Giuseppe Sprovieri and arranged for thirteen of his paintings to be included in the Free International Futurist Exhibition that opened in April 1914. The Galleria Sprovieri also offered Depero an occasion for his first foray into performance (figure 2). On March 29, 1914, during an afternoon event, he played the dwarf Scetavajasse in Piedigrotta, and a few weeks later he was a chorus member in the Funeral of a Passéist Philosopher. Inspired by the Dynamic and Synoptic Recitations in Sprovieri’s gallery, Depero also began to write his first poems in ‘onomalingua’ (onomatopoetic language) and performed these on various occasions.3

The Kinetic and Noise-Producing Ensembles (1914–1916)

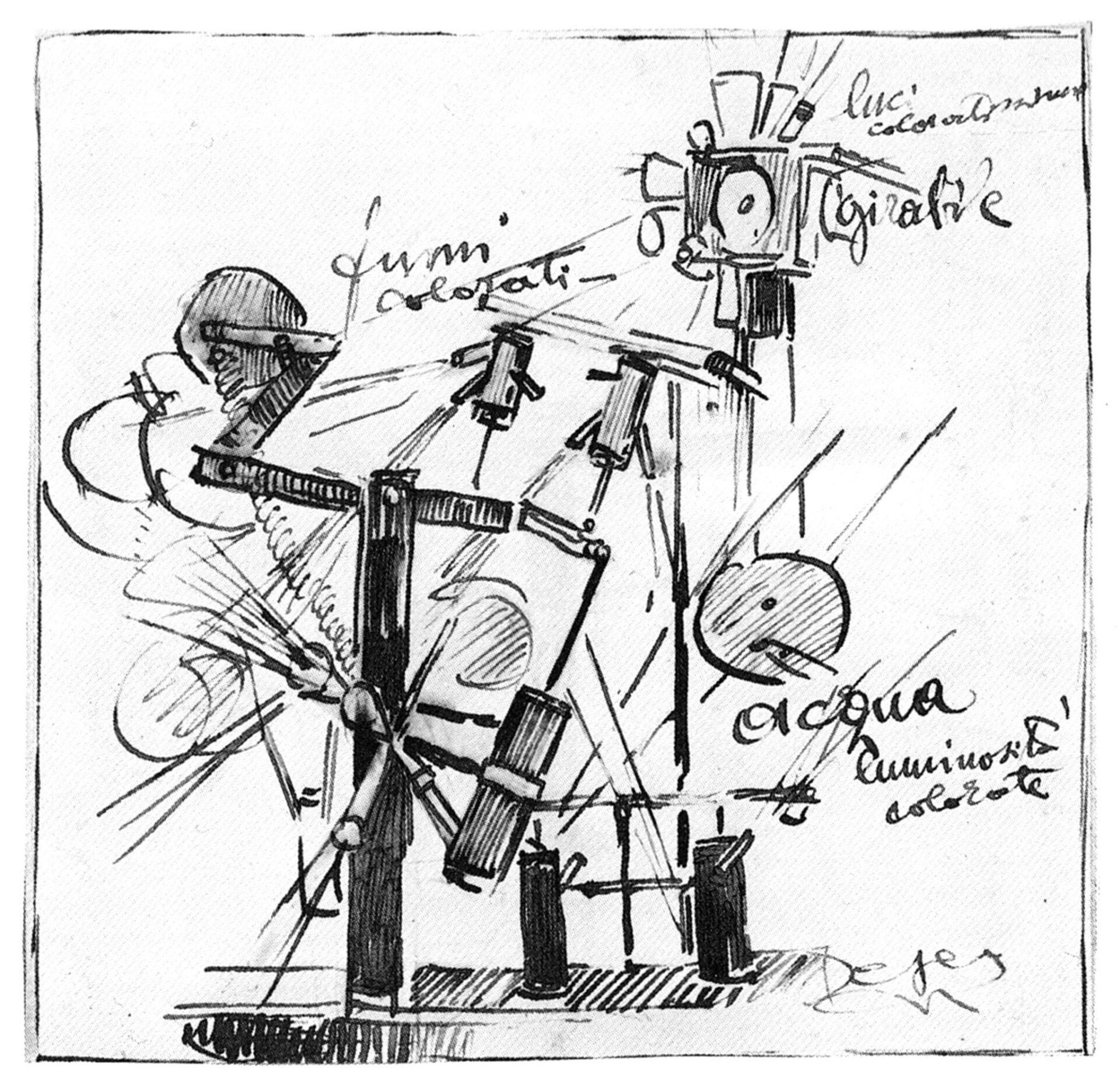

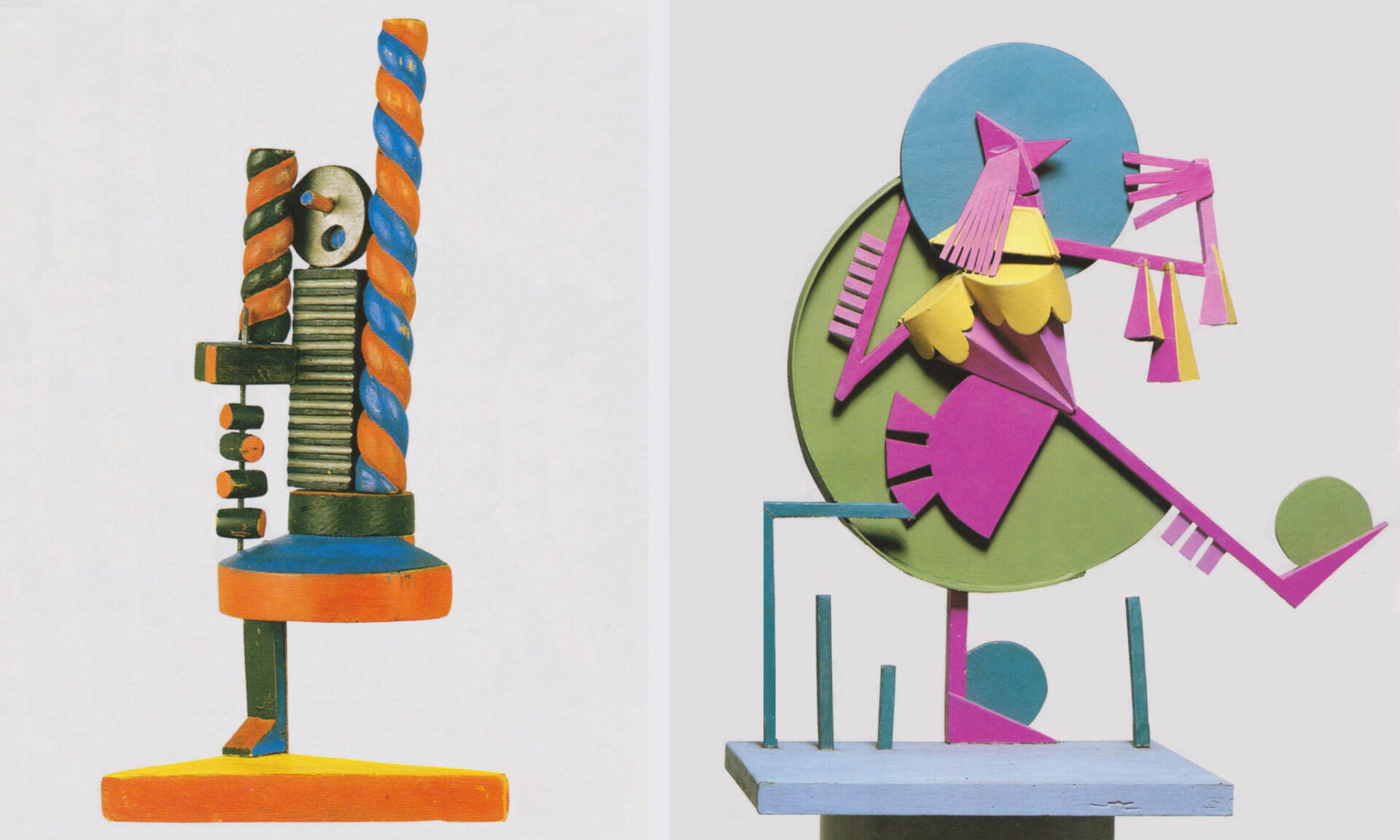

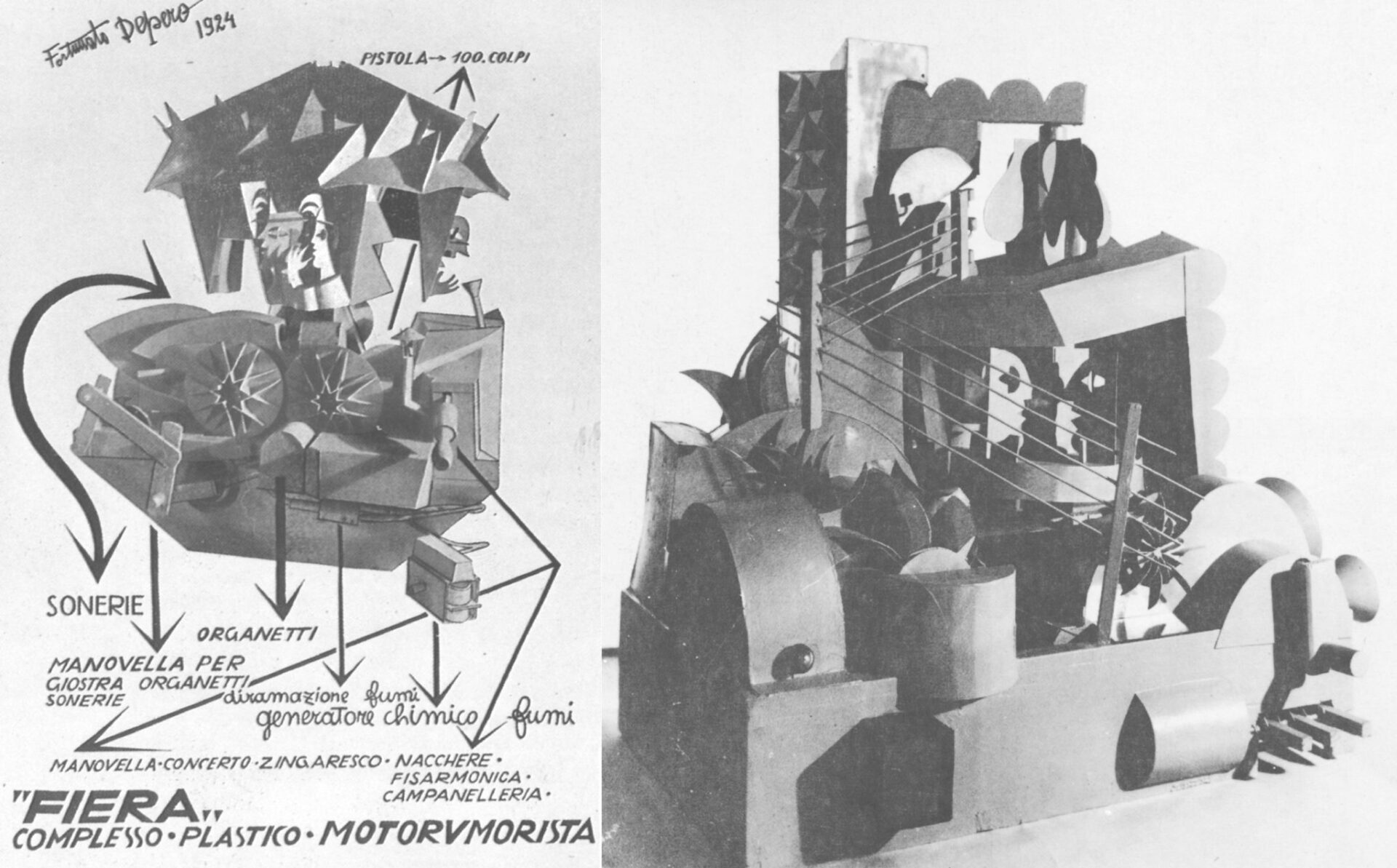

The focal point of Depero’s interchange with Balla were the Complessi motorumoristi (Kinetic and Noise-Producing Ensembles), a further development from the sculptures that Boccioni had exhibited in Paris in June–July 1913 under the heading Ensembles Plastiques (figure 4). Further inspiration was provided by Carlo Carrà’s manifesto La pittura dei suoni, rumori, odori (The Painting of Sounds, Noises and Smells) of August 1913, which similarly discussed insiemi plastici astratti (abstract plastic wholes) as “corresponding not to our sight but to the sensations which derive from sounds, noises, and smells.”4

Depero described his main artistic endeavor in this period as superamento del Quadro (overcoming the confines of the picture frame).5 To do so, he pursued a trajectory that led progressively from polymaterial sculpture to plastic architecture to “colorful compounds in motion,” in which he tried to give expression to “mobility and the magic sense of transformation”6 as well as “our mechanical, electro-speedy, magically artificial and ultra-noisy sensibility.”7 Whilst there was much overlap in Depero and Balla’s conception of the abstract correlations between color, sound, and movement, Depero seems to have been a person with a stronger ludic sense. His emphasis on gioco libero (free game) and magic may have been encouraged by Marinetti’s proto-Surrealist concept of the meravigliosa (marvelous) presented in the Variety Theatre Manifesto of October 1913. Playfulness was certainly a prominent aspect of Depero’s artistic personality: it not only dominated his whole creative career, but also became a core element of his theatrical œuvre.

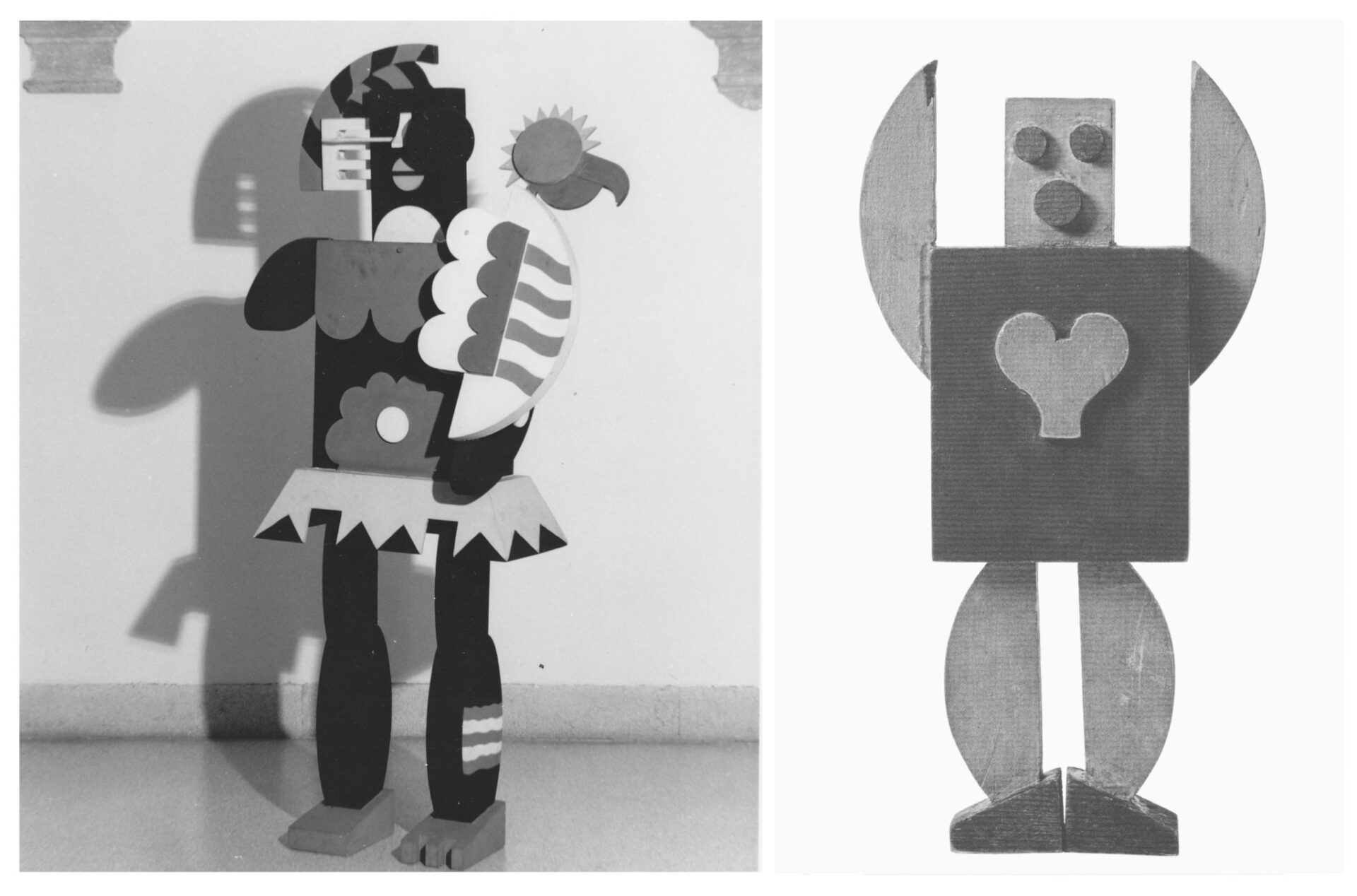

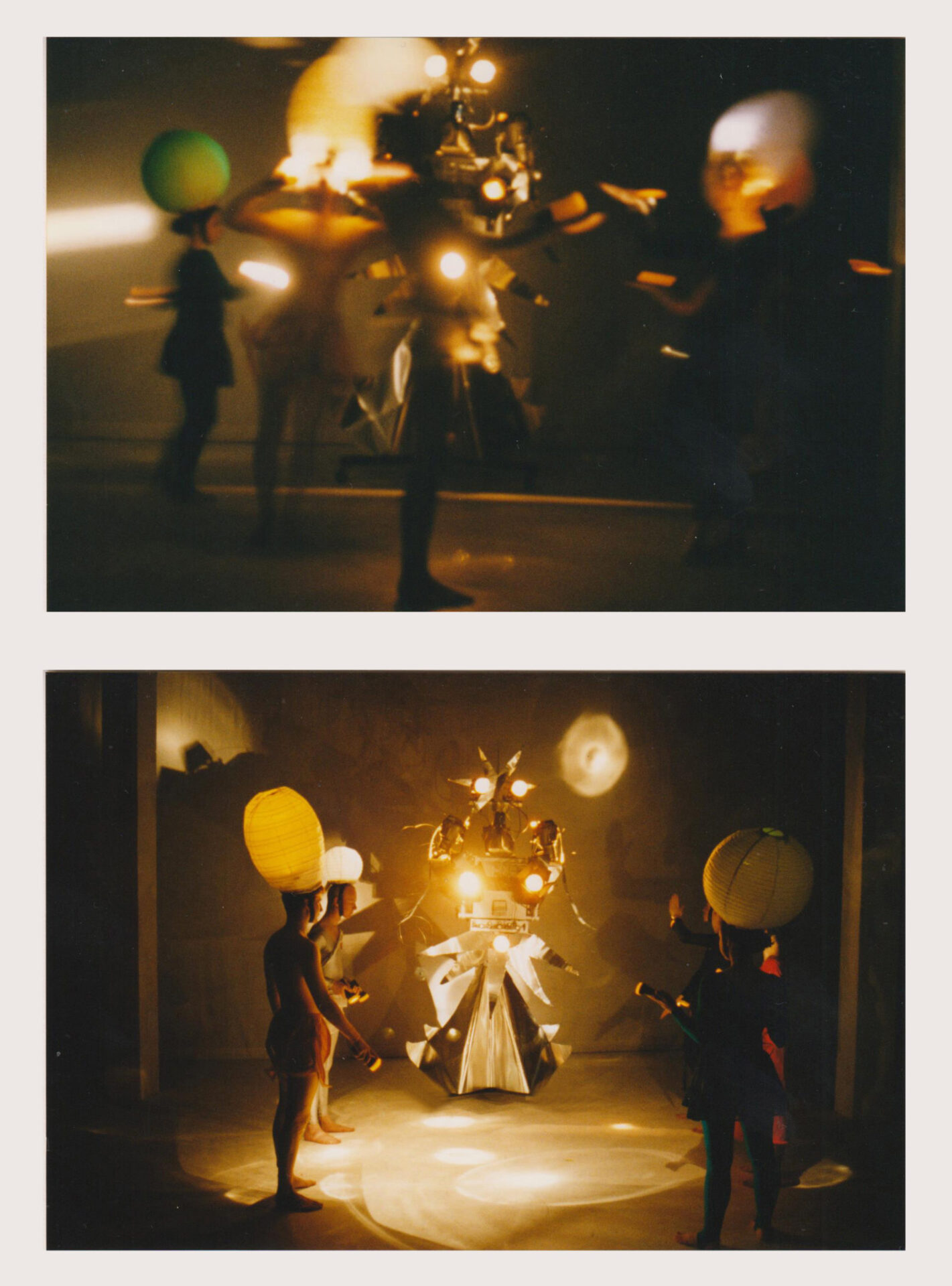

Depero’s noisy, movable, polymaterial sculptures of 1913–1915 were a complement to a marionette he called essere vivente artificiale (Artificial Living Being; figure 5). This organism was designed to operate as an actor in a scenic environment with “rhythmically vibrating elements, from which will emerge and disappear animals and clouds, open and close doors, windows, eyes and mouths.”8 The innocence and playfulness of these constructions ensured that they would stimulate in the audience a sense of wonder, amazement, fascination, and joy.

Depero’s Artificial Living Being was a mechanical toy that could be fitted with elements of light and sound. Such an entity was no longer painting, no longer sculpture, no longer architecture: it was a non-ephemeral spectacle. Ultimately, what Depero hoped to achieve was “ballets constructed with applications of automatic contraptions which dance new and entertaining mimes”9 (figure 6). He wrote a descriptive scenario to be used as the basis for such a performance:

A cityscape with the sea in the background. A group of mechanical luminous flowers. Horses come down the street. In a guesthouse, a group of mechanical men are having lunch. The door to the restaurant closes and on the upper floor a curtain opens. We see how a clown and a doll get up from the floor and strut about in a comical gait. When the curtain closes again, we see in the far distance the horse and cart from the first scene and a boat sailing across the sea. On a meadow, a large flower emerges. Some blades and spirals grow out of its bud and flutter in the wind, while on the border of the meadow other flowers rotate around their own axes and radiate strange and colorful vibrations.10

Although we do not know the exact date when this scenario was written, it seems to anticipate the 1916–1917 Song of the Nightingale and the Plastic Ballets. In these scenic creations, Depero’s work from 1913–1914 was taken a step further: they were presented to an invited audience, and ‘sculpture’ thus turned into ‘theatre.’ This, one might say, became Depero’s artistic program for the next two years and led him quite naturally into the world of dance and puppetry.

Mimismagia

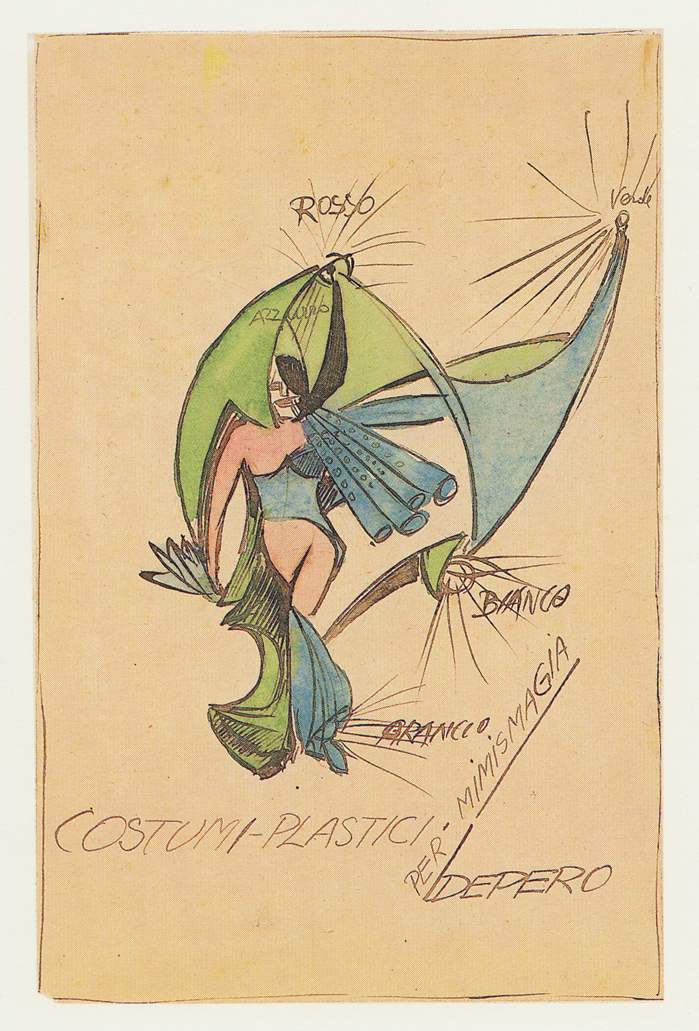

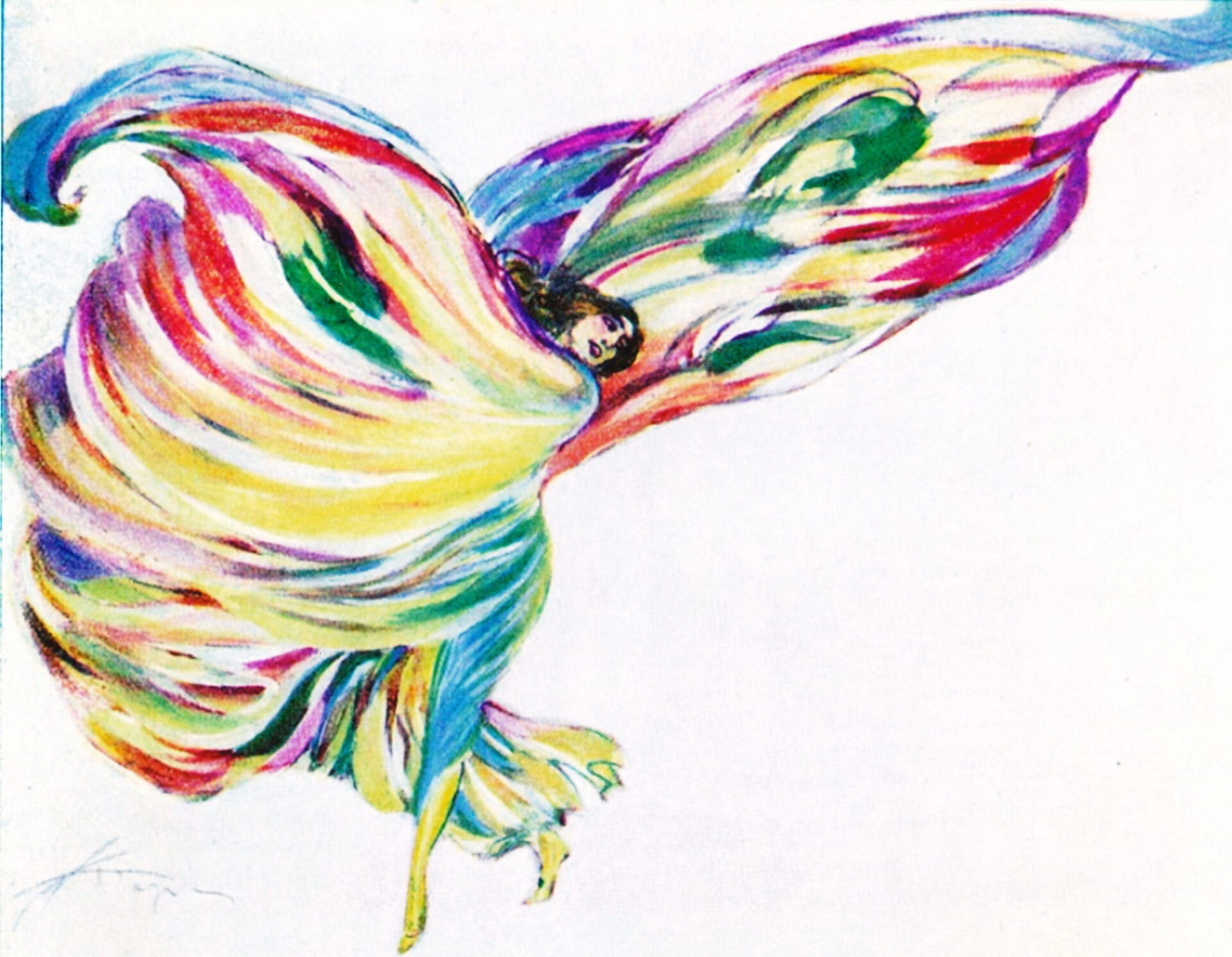

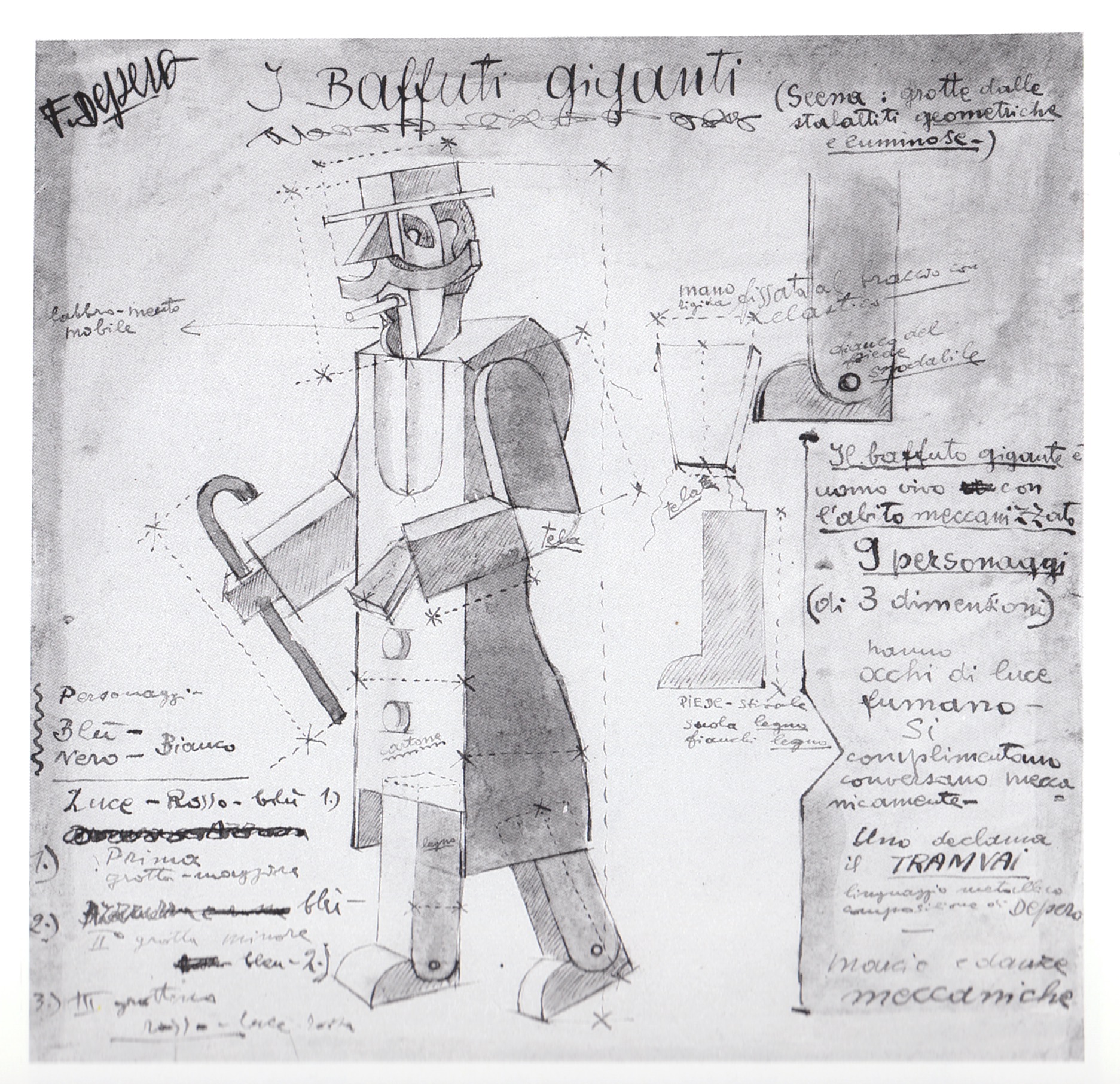

In 1916, Depero worked on a project with three dancer-robots, from which some costume designs survive. When they were first exhibited at the Galleria Sprovieri, the critic Mario Broglio described them as “externalized emotions presented in a mimic-acrobatic dance with sculpted costumes in transformation”11 (figure 7). Colorful, transparent drapes were attached to wires and poles and furnished with a number of colored lights. In order to puzzle and surprise the audience, the actor could operate hidden devices that transformed the costumes and produced rhythmic noises. The idea for this ‘magic mime’ was derived, it seems, from Loïe Fuller’s dances with illuminated stage costumes (figure 8).

Mimismagia was an unfinished project that explored the synesthetic correlations between different sense impressions. Depero’s name for these costumes was Vestito ad apparizione.12 Such ‘apparition-like outfits’ were conceived as “magical-mechanical equivalents to a complex simultaneity of forms, colors, onomatopoeic sounds and noises.” The material was to be sewn together so that the actor’s movements and gestures would “release certain springs and open fan-like contrivances, accompanied by bursts of luminous apparitions and rhythms of noise-producing contraptions.”13

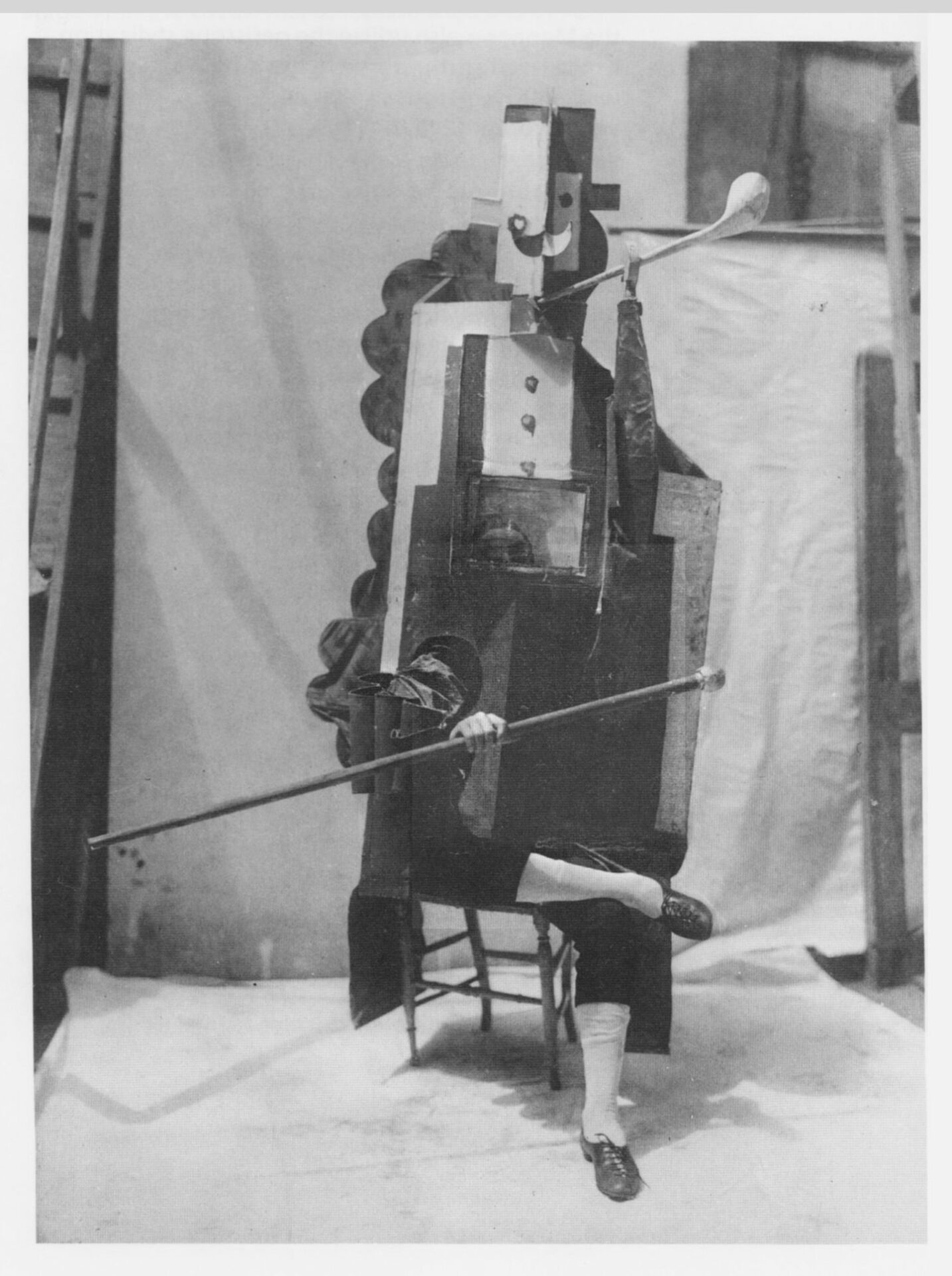

When used scenically in a dramatic mime, the costumes helped to convey a story, to provoke dramatic emotions, and to function within a stage set. The dancer was subservient to the outfit – an idea that was developed at that time, on a much more advanced level, by the Ballets Russes in the ballet Parade (figure 9). But Depero did not see the kinesphere of his dancer-robot in isolation from the surrounding scenic space. This becomes apparent in Notes on the Theatre, written circa 1916.14 Here, Depero imagined the transformations of the dancer as events taking place within a simultaneously changing environment. He wanted to abolish fixed scenic architecture and replace it with a multi-level, multi-perspective, changeable stage set. Wings and backdrops were to turn on pivots; ceilings would move up and down; pieces of furniture would chase each other or the dancers (figure 10).

Depero saw his stage as being fitted with highly advanced mechanical contraptions that would create tricks and surprise elements – like a ‘magic box’ or mechanical toy theatre in which to perform ‘magical mimes’ – as in Fiera (Fair; 1924) or Panoramagico (Panoramagic; 1926; figure 11).15

Il canto dell’usignolo and the Balli plastici

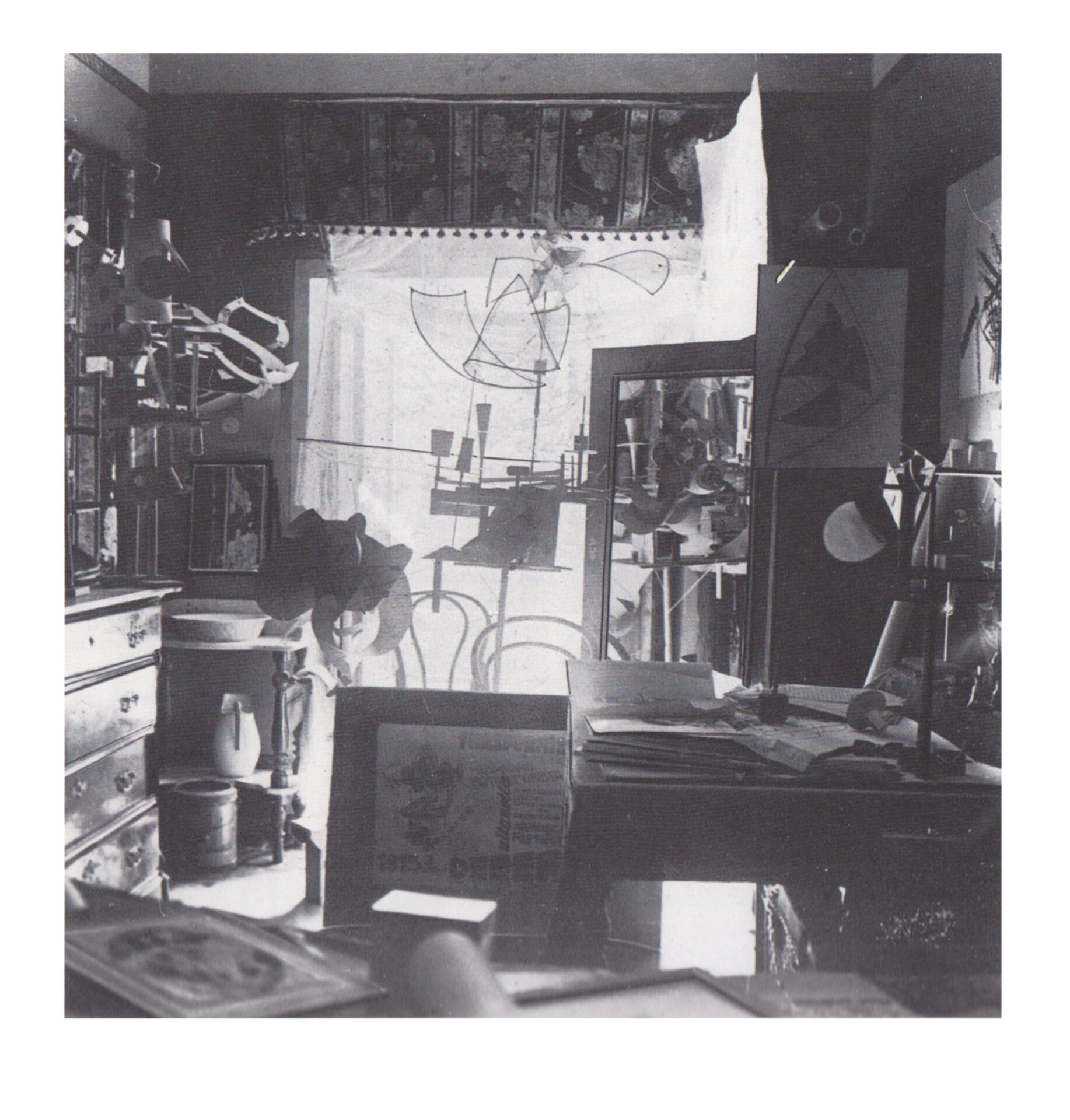

In September 1916, Sergei Diaghilev and a small group of dancers from the Ballet Russes arrived in Rome and began to plan a short season of new works to be presented at the Teatro Costanzi. Diaghilev’s intermediary to the Roman art world was the Russian émigré Mikhail Semenov, who had bought one of Depero’s paintings at the Prima mostra libera futurista (First Free Exhibition of Futurist Art) at the Sprovieri Gallery in 1914. In April 1916, the Russian impresario also acquired one of Depero’s paintings exhibited at the Galleria di Corso Umberto. After a personal meeting in Balla’s studio, Depero was given a contract to design and construct costumes as well as a stage set for a ballet version of Stravinsky’s first opera, Le Rossignol, to be completed by February 15, 1917 (figure 12).

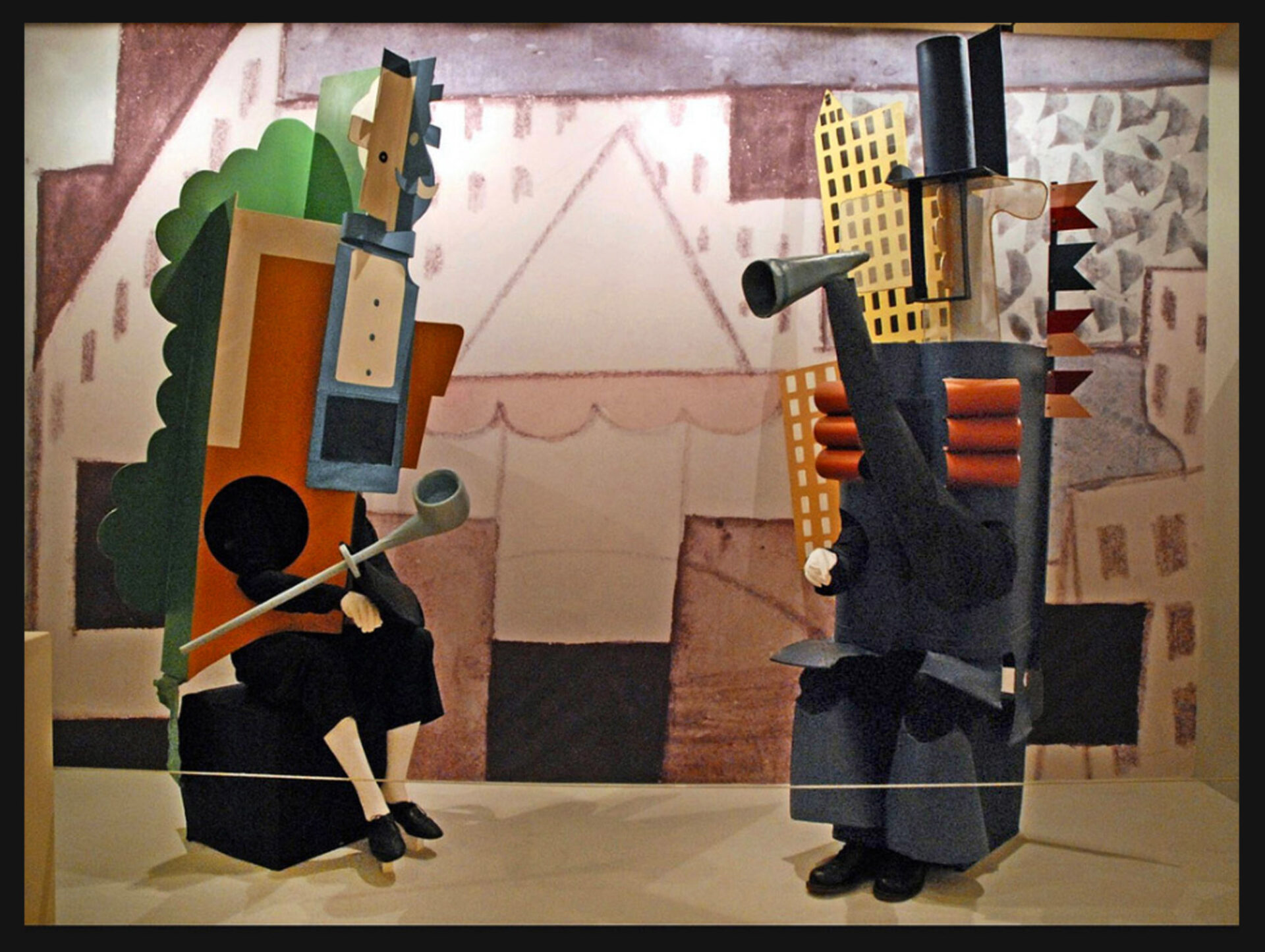

Leonide Massine visited Depero’s workshop to try out some of his costumes, which looked quite similar to those for Mimismagia, but without electrical light appliances. Like Diaghilev, Massine was rather worried about their restrictive quality, but, unlike Picasso’s huge cardboard encasements for Parade (figure 13), they were at least made up of many parts connected by strings, wire, and hinges. A few days after the deadline, the constructions must have been more or less completed, for the English composer Gerald Tyrwhitt wrote to Stravinsky, “A great Deperesque work is being prepared for your Nightingale: I saw the sets and costumes, which are very, very pretty.”16 Stravinsky subsequently finished the score on April 4 and came to Rome to conduct the performance at the Teatro Costanzi. However, for some unknown reason the ballet was not included in the program presented by the Ballets Russes at the Teatro Costanzi on April 9 and 12, 1917.17

Although Depero’s ideas for The Song of the Nightingale were never attempted in performance, the surviving designs, photographs, and written accounts give us a fair impression of the concept behind his construction of an ‘enchanted garden,’ in which the nightingale moved the Chinese Emperor to tears with its song. It was made of “bent cardboard, clipped, and inserted, forming cones, cylinders, slices. Sharp carnations, bell-flowers with indented edges, pointed leaves in bunches and couples, fluorescent discs and triangles, thorny bushes of forked branches, a crystal-like and metallic fairy flora”18 (figure 14).

The central group of flowers was five meters high, and the open blossoms measured two meters in diameter. The lower thicket of plants had large, sword-like leaves and menacing thorns. Snow-white bell-flowers were mixed with a dazzling array of pink, blue, scarlet, yellow, orange, and lilac blossoms. It was “an intricate mechanical garden in fluorescent colors… an authentic crystallization of a festive orchestra.”19 As to the execution of the costumes, Depero himself described his constructions thus:

Rigid costumes, solid in style, mechanical in movement; grotesque enlargements of arms and large, flat legs; hands made of cans or discs or fans with long, pointed and rattling fingers; golden or green masks showing only one nose or a set of eyes or a luminous, smiling mouth made out of a mirror; bell-shaped coats and trousers and shirt-sleeves; all of them polyhedral and asymmetric, all of them detachable and mobile.20

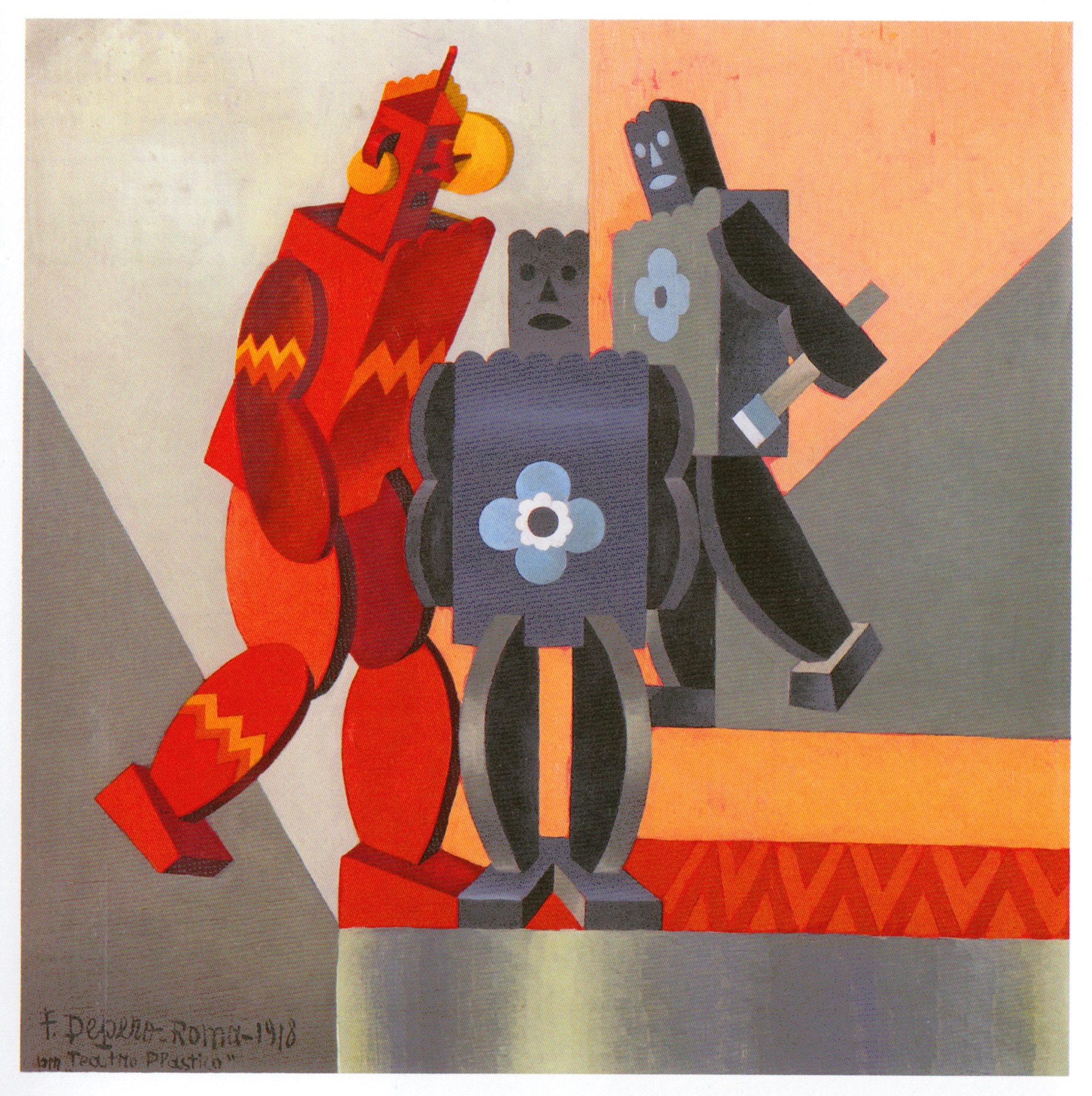

Depero’s costumes possessed the stiff rigidity of sculptures, yet were also light and pliable (figure 15). Surviving drawings indicate that dancers were typically hidden behind ever-changing attire so that they resembled the Artificial Living Being Depero had conceived in 1914. Dynamic forms, sounds, and colors created “a stupefying image of the plastic man of a new world.”21 In these designs, Depero relinquished the idea of dance happening in front of a backdrop (or a flat, profiled up-stage construction, as in Picasso’s Parade).22 Fully integrated into the scenic architecture, the costumes were meant to form a Gesamtkunstwerk (Total Work of Art). The dancer functioned as a motor that propelled the assemblage into action and turned the whole stage into a unified chromatic, phonetic, and kinetic construction. During the summer of 1917, Depero wrote several short plays, Suicidi e omicidi acrobatici (Acrobatic Suicides and Homicides), Avventura elettrica (Electric Adventure), Ladro automatic (Automatic Thief), Sicuro (Safe).23 They were exercises in a new genre variously referred to as dramma plastico futurista (Futurist plastic drama), dramma plastico-teatrale (plastic-theatrical drama), or il primo teatro plastico teatrale Depero (first plastic-theatrical Depero theatre). These playlets were to be performed by marionettes or robots, figures that, despite resembling human beings, exhibited stylized movements and transformations that went far beyond naturalistic conventions. Great prominence was accorded to light and color instead of spoken dialogue.

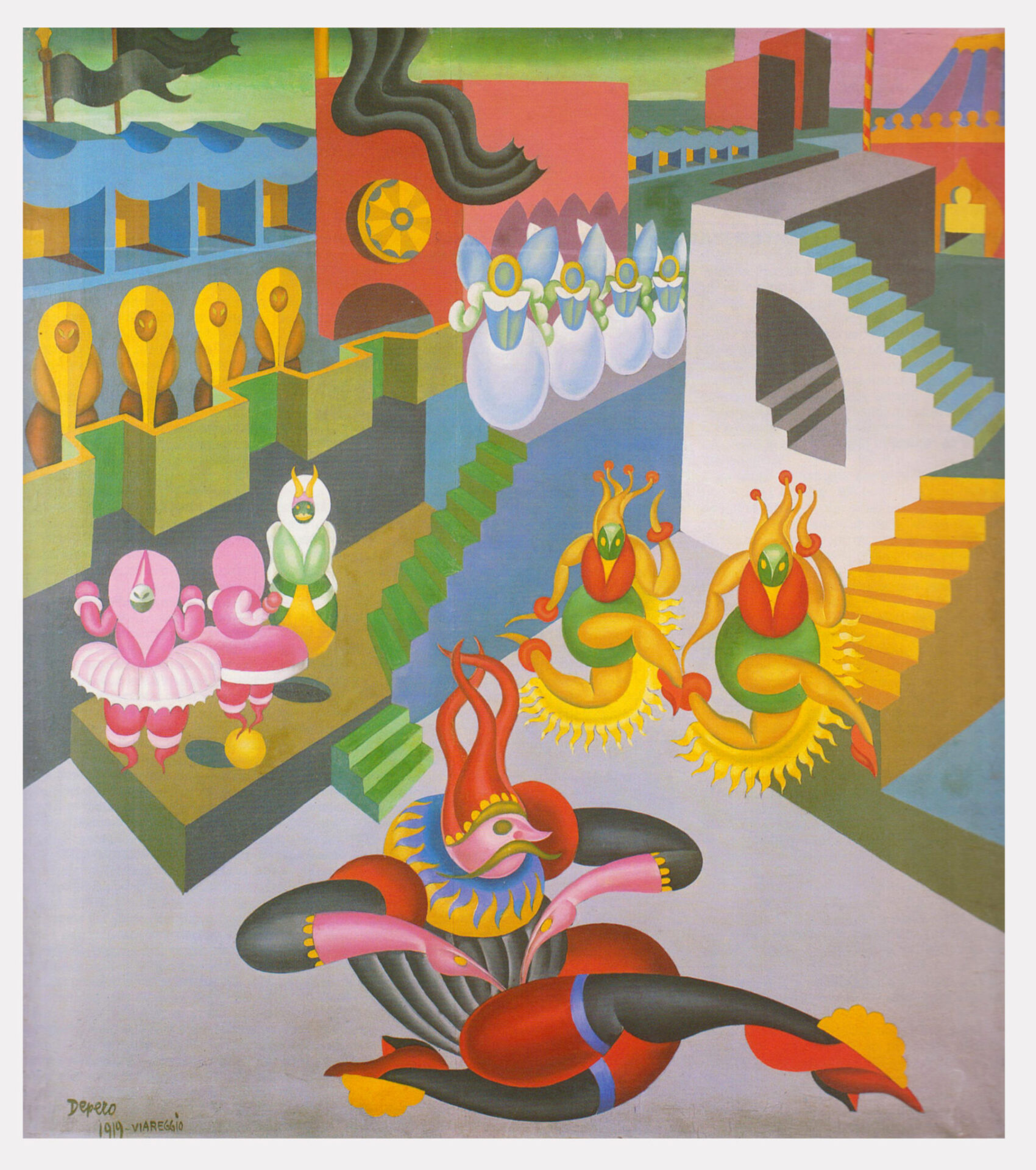

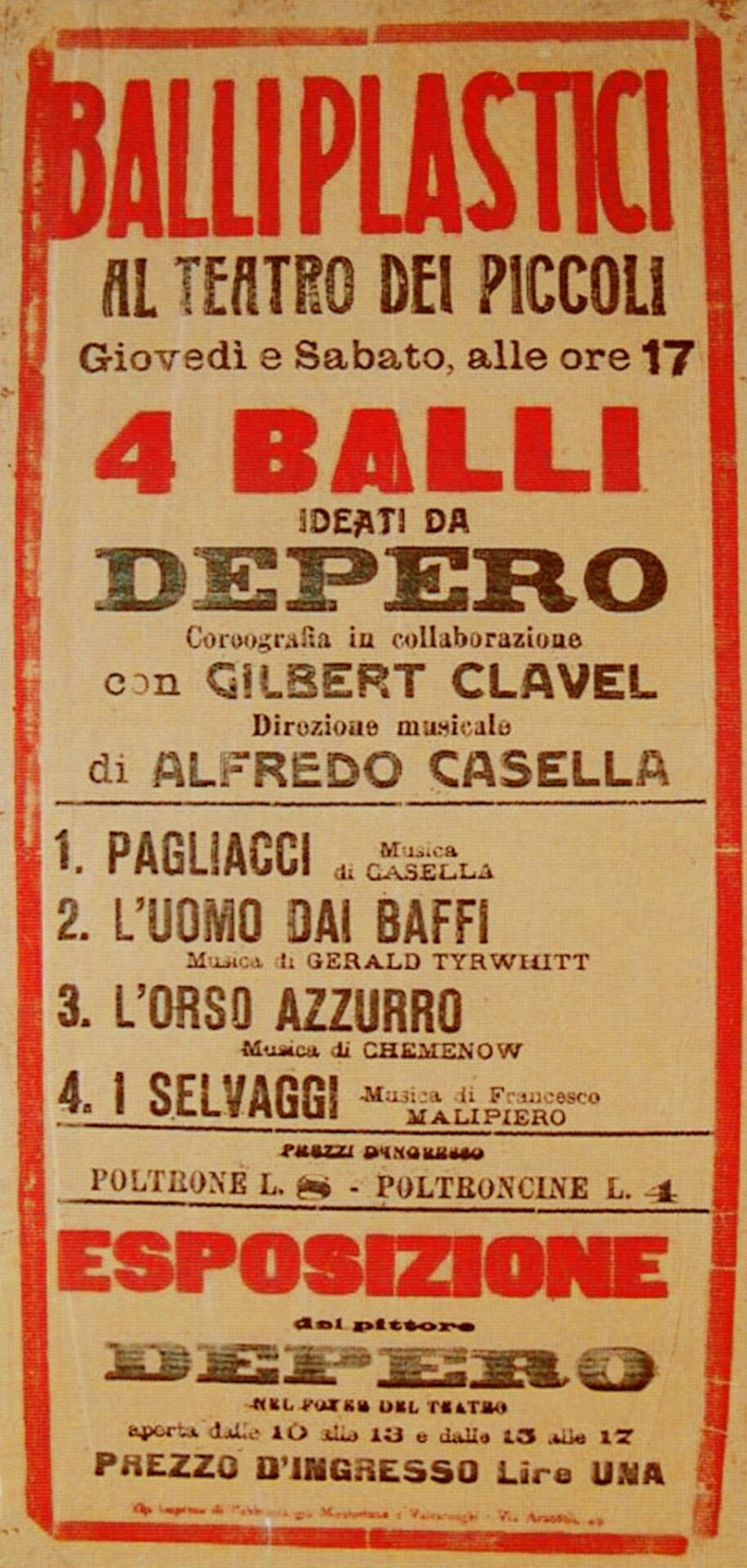

In the autumn of 1917, Depero persuaded Vittorio Podrecca, director of the Teatro dei Piccoli, to try out some of his scenarios in the next season of the Gorno Dell’Acqua marionette company. Depero was given a few months to construct the marionettes and scenery. He was also negotiating with composers to arrange existing music or to have new scores written for the spectacle. The final versions of the scenarios were written in close consultation with the puppeteers of the Gorno Dell’Acqua company, and on April 14, 1918, four out of the five planned pieces were presented to the public (figure 16).

I pagliacci (The Buffoons), with music by Alfredo Casella, revealed a brightly-lit village constructed in a stylized, Cubo-Futurist fashion (figure 17). The green undulating landscape contrasted with the crimson zig-zag contours of the houses painted on the backdrop and the profiles of the wings. Downstage one could see two multicolored trees constructed from geometric and spiky materials. A line of clowns marched on stage to the rhythmic music of Maestro Casella. The puppets were 30 cm (11.9 in.) high and covered with white lacquer and metallic-blue paint. Their clumsy movements turned into a heavy, accentuated dance accompanied by a Russian folk tune played on a piano. After their exit, a large ballerina (85 cm high; 33.5 in.) constructed from colorful cones, discs, and prisms and wearing a pink tutu stalked onto the stage, followed by a clown in a red and yellow costume. After a dance, as well as a bit of horseplay, the two characters directed their attention to a hen that began laying eggs.

L’uomo dei baffi (The Mustachioed Man) with music by Gerald Tyrwhitt portrayed a drunken man with a large mustache walking down a street paved with gold (figure 18). Suddenly, he grew in size and multiplied, giving rise to a whole string of uomini dei baffi (mustachioed men) that all looked like miniature versions of himself. These little men drank from glasses illuminated by colored light and began to dance; however, the large marionette moved with such heavy steps that the whole scenery began to wobble. A blue ballerina subsequently entered, presenting a more elegant version of the terpsichorean art. Furthermore, black cat eating a white mouse, as well as a shower of cigarettes falling from the flies delighted three of the mustachioed men, making them stagger about in a delirious dance. Next there came a short interlude in the form of Ombre (Shadows) – a symphony of abstract black and grey shapes juxtaposed with a light-play of vivid colors – which offered a visual interpretation of a composition by Béla Bartók. This was followed by L’orso azzurro (The Blue Bear), a clumsy and grotesque dance between a bear and a monkey that was again accompanied by Bartok’s music.

The last piece was I selvaggi (The Savages) with music by Gian Francesco Malipiero (figure 19). A group of red savages, downstage, and a group of black savages, upstage, lined up to fight for the possession of a Great Female Savage (La grande selvaggia). In the middle of this balletic combat the lights went off, and one could see amidst the darkness the scintillating green eyes of a snake slithering across on stage. After this, two representatives of the tribes of savages fought over the female savage. Then, suddenly, the lights went out again, and the spectators were captivated by yet another fascinating spectacle: the Great Female Savage opened her belly to reveal a silver baby savage dancing a minuet (figure 20). Eventually, the tiny savage exited the uterus, jumped onto the main stage, and the green snake re-emerged to gobble the infant up. Finally, the performance concluded with a revue-type dance and a procession of all the show’s characters.

The Balli plastici were a masterful presentation of Depero’s theatre aesthetics as they offered a mesmerizing experience of a futuristically refashioned universe (figure 21). The performance ultimately gave rise to two theoretical essays24 in which Depero explained the principal objectives behind this mondo plastico (Plastic World):

- To progress from vague Impressionist techniques of pictorial representation to precise three-dimensional constructions that form a unified and total work of art, where the disparate elements retain their freedom of signification.

- To avoid any mimetic imitation of nature and instead construct a new artificial reality according to artistic principles.

- To avoid psychology and to express emotions through the plastic drama and rhythmic dynamism of materials.

- To turn sculpture into architecture and to make the new environment a multi-sensorial world, in which all visual and aural forms of expression are incorporated.

- To anticipate in the theatre a transformed environment for all cultures and races, including humans, animals and artificial beings.

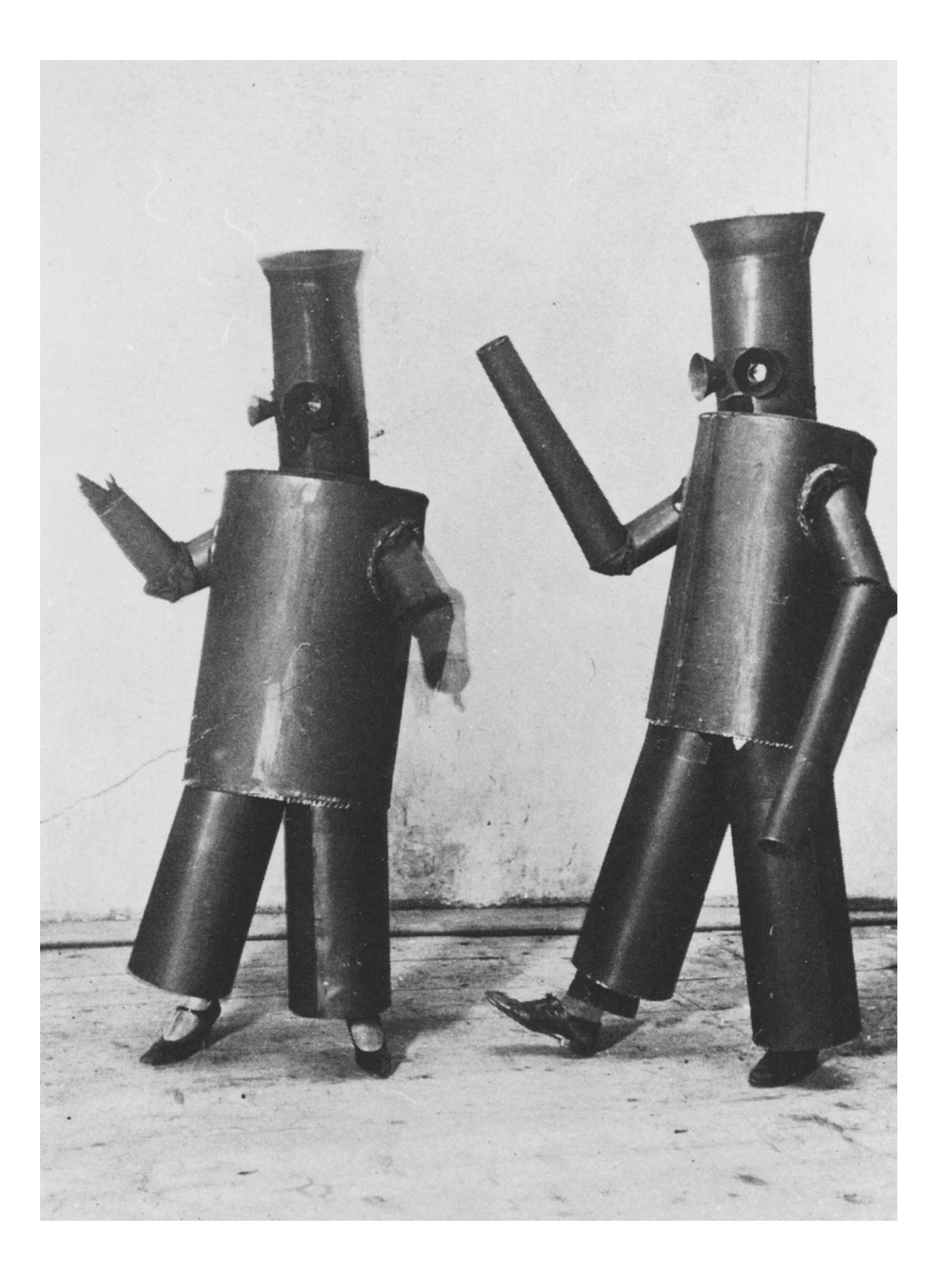

Anihccam del 3000

Machine aesthetics were a popular field of theatrical exploration in many countries, ranging from capitalist America (via Fascist Italy) to Bolshevik Russia. Well-known examples were the commercial girl revues, the experiments at the Bauhaus stage workshop, Vsevolod Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and Nikolai Foregger’s machine dances. Within the Italian Futurist movement one could find a wide array of attitudes towards the machine. The young artists Ivo Pannaggi and Vinicio Paladini looked at modern technological civilization from a Proletkult angle. They penned a manifesto25 in which they called for the working class to unite under the sign of the machine and to erect a new civilization based on change, innovation, and progress. Their Ballo meccanico futurista (Futurist Mechanical Ballet), presented on June 2, 1922, at the Casa d’Arte Bragaglia in Rome featured a proletarian Man-Machine, a cross between a human and a mechanical being (figure 22).

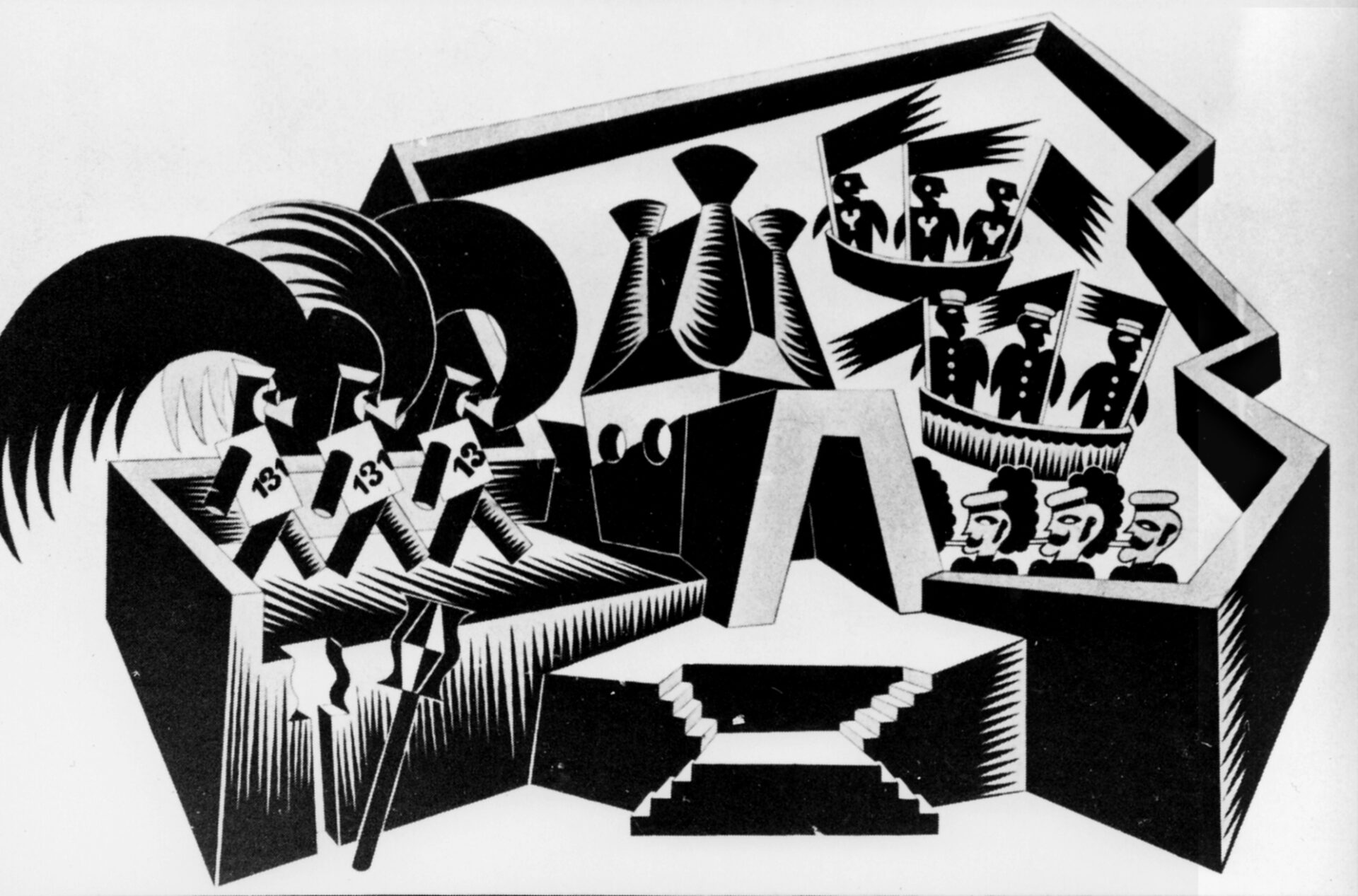

Entirely different was Depero’s Anihccam del 3000 (Machine of the Year 3000, spelled backwards). This machine drama formed part of a program that Rodolfo de Angelis and his Compagnia del Nuovo Teatro Futurista (The New Futurist Theater Company) presented on January 11, 1923, at the Trianon in Milan (figure 23). A close examination of this stage work26 reveals that Depero’s machine aesthetics were not rooted in the world of factories urban conglomerations; they seemed as if they had come out of a toy shop. Depero’s macchinismo (machine cult) oscillated between magical playfulness and grotesque humor. Whereas in the 1910s he tended to represent human behavior with marionettes, in the 1920s he created machines to which he assigned human psychology. At this time, a machine that greatly fascinated him was the locomotive.

The reviews of Anihccam del 3000 recount how, in these performances, a uniformed man used a flag to pilot two locomotives into a railway station (figure 24). When these vehicles reached a center-stage position, they began a dance that conveyed that the two machines had fallen in love with the stationmaster. A song in onomatopoeic gibberish simulated a conversation between the man and the two humanized machines.

In 1925, Depero travelled to Paris, where he was exhibiting at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs. In the music-halls, Revues Nègres and Ballets Suédois, he watched “theatrical spectacles of a modernity pushed to its utmost limits, precise in their lights, dances, choruses, stage sets, and costumes – settings of a mechanical, North-American Futurism.”27

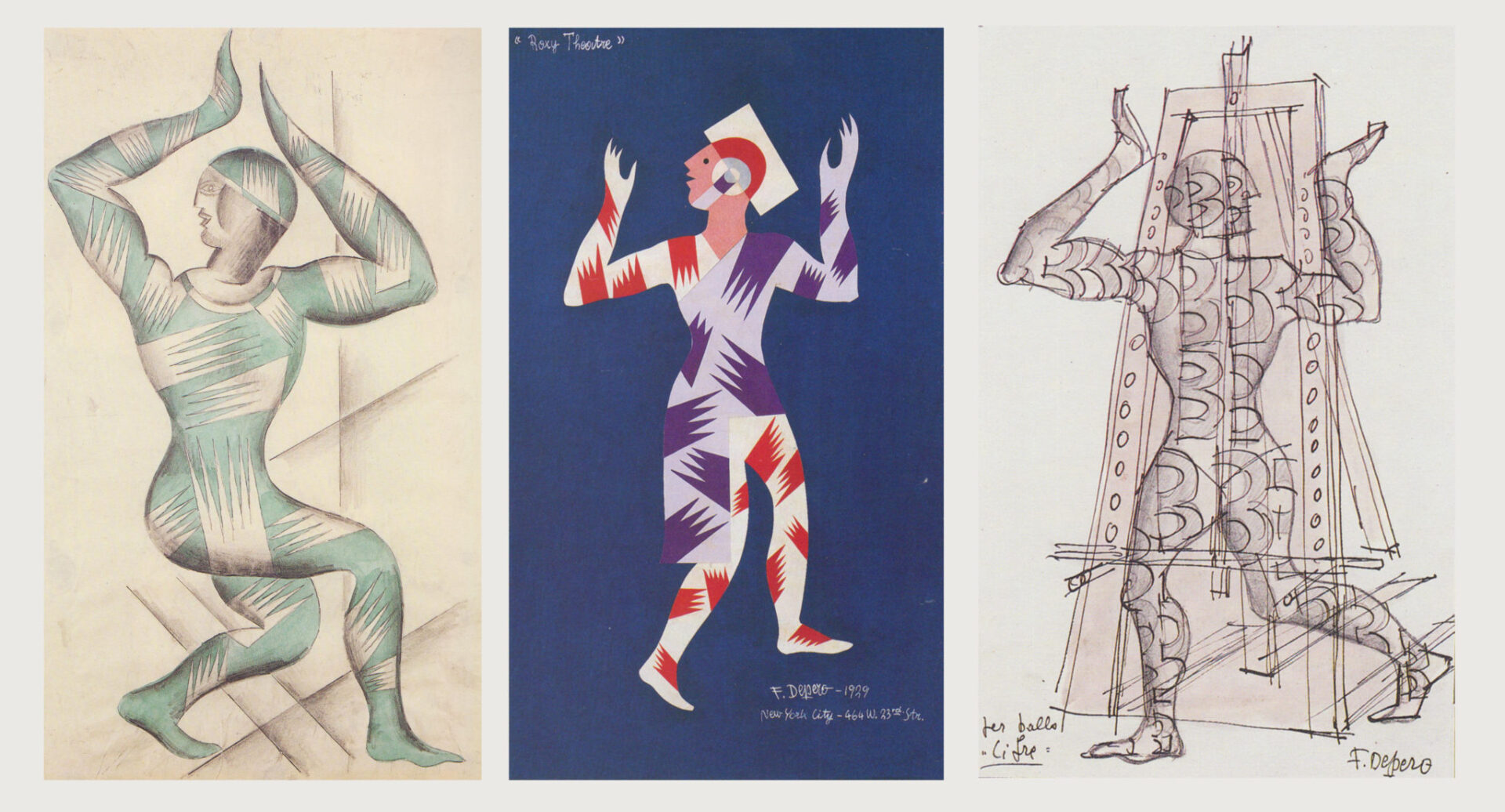

This experience inspired him to write several new dance scenarios for mechanical or electrified dancer-objects, amongst them Pennini e matite (Pen Nibs and Pencils) and Motolampade (The Moving Lamps; figure 25).28

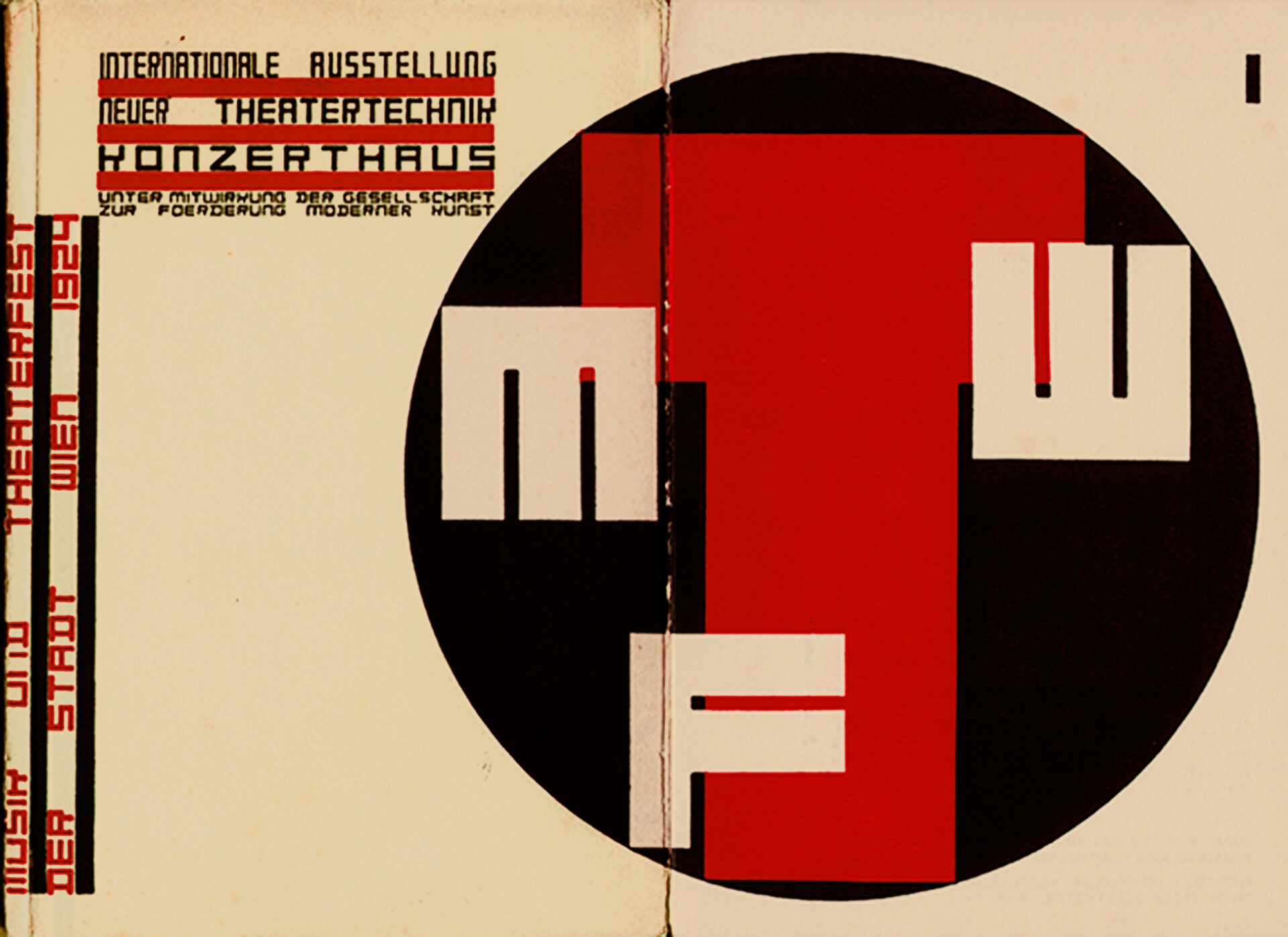

The ‘New Babel’ New York

Depero never attempted to present his ballets on an Italian stage; he rather sought to have them produced in an American theatre. In Paris, he had made the acquaintance of Friedrich Kiesler, who was the organizer of the International Exposition of Theatre Technology in Vienna (figure 26). When this show was brought to New York in 1926,29 thirty of Depero’s designs were included in the exhibition. Around this time, he was also invited to hold a solo show of paintings. After receiving a subsidy from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a donation from the industrialist Benvenuto Ottolenghi, the artist thus set off from Genoa to conquer the North American public.30

Once he had settled in New York, Depero visited various revue and variety shows on Broadway. He referred to these performances as a “speedy theatre of modernity” and was amazed by their “rotating, agile, spiraling and mechanic dances,” as well as their aesthetic of “luminous zig-zag lines” which, he claimed, divided and multiplied “the visual effect of the movements.”31 The sheer physicality, energy, and frenetic rhythm of the Broadway shows and the technical sophistication of stage devices appeared to him like a Futurist dream come true.32

Throughout his two-year stay in New York, Depero worked on sketches, collages, graphic designs, paintings, prose pieces and poetry that sought to capture the machine-age civilization he was experiencing in New York. For the theatre, he wrote two scenarios: Quattro bocche assetate (Four Thirsty Mouths) and La voce della antenna (The Voice of the Antenna).33 However, neither the commercial nor art theatres of the city were ready to take on such avantgardistic fare.

In January 1929, at the opening of his one-man exhibition at the Guarino Gallery, Depero met Massine again, who in 1916 had helped him to get a contract to design Rossignol for the Ballets Russes. Massine introduced Depero to another Russian theatre impresario, one Mr. Leith, the theatrical agent Berta Cutti, as well as Leon Leonidov, the artistic director of the Roxy Theatre.34 Consequently, the artist turned his hand again to the ballet scenarios Pennini e matite and Motolampade (figure 27) and also drew up ideas for a stage work with mobile scenery, The New Babel, to be choreographed by Massine at the Roxy Theatre.35 Depero additionally constructed scenery, props, and costumes for a play focused on the machine culture of the United States, entitled The Black King. For unknown reasons, these projects were never realized on stage.

Depero only managed to design the costumes for a parade at the Roxy Theatre in April 1929 and the sets and costumes for American Sketches at the Wanamaker’s Auditorium in June 1929.36 Considering the working methods at the Roxy Theatre, as well as the fact that Leonidov essentially needed an army of designers to work on his conveyor-belt style productions, one can understand why Depero’s role on these projects was even less significant than that of Massine (who had been shocked to discover that Leonidov expected him to provide a new ballet every week, in addition to other theatrical divertissements).37

In a 1929 newspaper article, F. T. Marinetti discusses “Depero’s triumphs in the United States.”38 Yet, close scrutiny of sources at the New York Public Library’s Dance and Theatre Collection and the Depero Archive in Rovereto, as well as newspaper articles during Depero’s time in New York, hardly confirms this success. There is, in fact, only one truly positive account of Depero’s work, and this was undoubtedly published by the artist himself. It is possible that Depero was even the author of this report, as its wording is, at times, identical to passages of Il grido della stirpe (The Cry of the Race), L’impero (The Empire) and an unidentified newspaper clipping.39

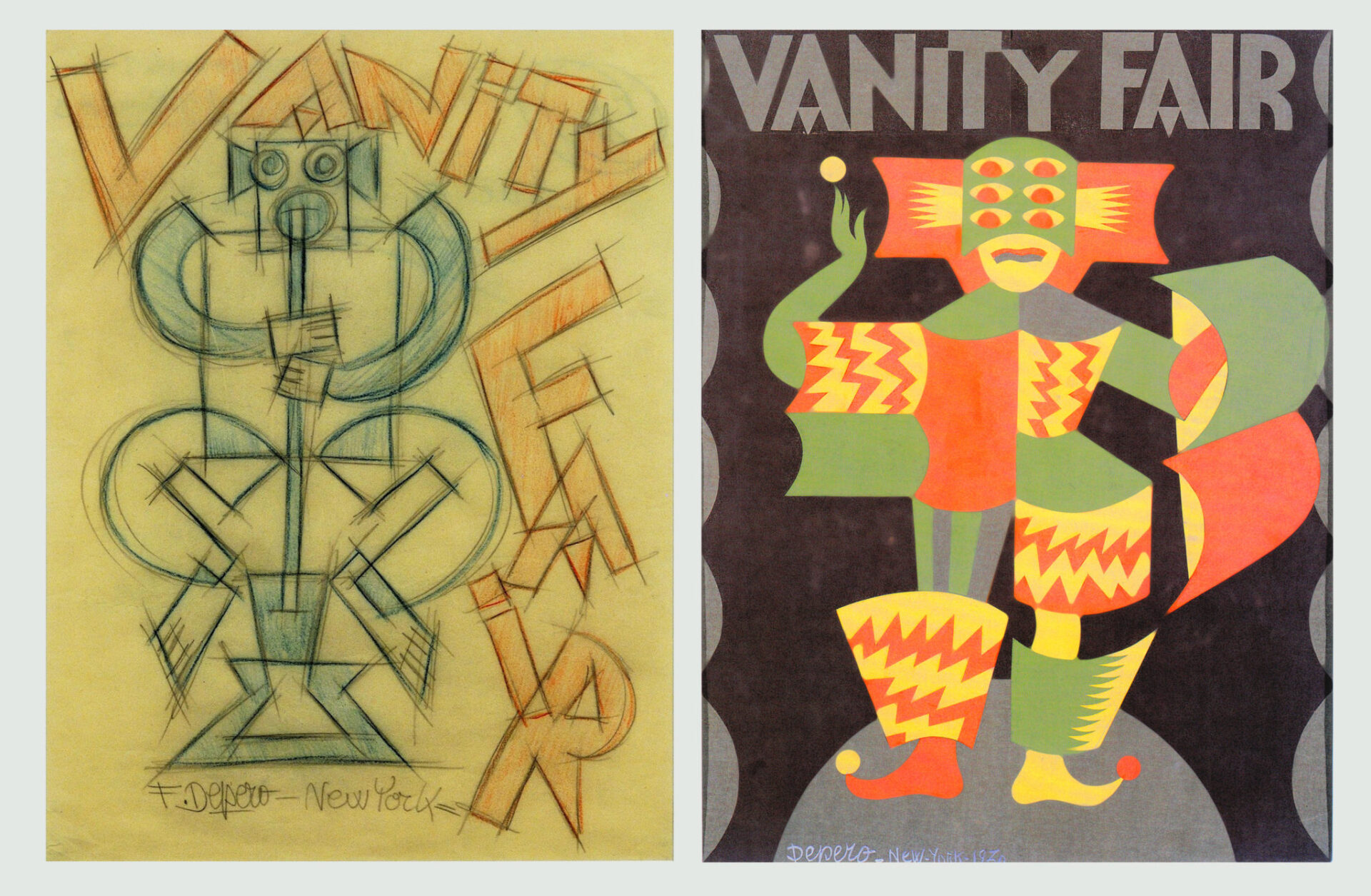

In conclusion, it appears that Depero’s attempt to break into the New York theatre world was, on the contrary, not particularly successful. His designs for a parade of ballet dancers, as well as a small solo section in a dance potpourri hardly amount to “a great success,” as Depero himself claimed. Even his foray into commercial graphic design, exemplified primarily by the covers he produced for Vanity Fair (figure 28), is counterbalanced by the magazine’s comment that the staff regarded Depero as “one of the most amusing figures among modern decorative artists.”40 This remark is, in a sense, analogous to the contemporary attitude in the United States towards the Italian Avant-garde in general, which, incidentally, is summed up in an earlier statement by Vanity Fair: “Futurism is, happily, a thing of the past. In polite circles the subject is now ignored, much as it has been a saddening aberration of the human mind. The multitude having had its laugh out, has passed on – to fresher objects of derision.”41

Bibliography

Apollonio, Umbro, ed. Futurist Manifestos. London: Thames and Hudson, 1973.

Axsom, Richard H. Parade: Cubism as Theatre. New York: Garland, 1979.

Belli, Carlo and Bruno Passamani, eds. Depero, 1892–1960. Spoleto: XXVI Festival dei due mondi, 1983. Exhibition catalogue.

Belli, Gabriella, Nicoletta Boschiero, and Bruno Passamani, eds. Depero Magic Theatre. London: The Italian Institute; Milan: Electa, 1989. Exhibition catalogue.

Berghaus, Günter. Italian Futurist Theatre, 1909–1944. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Broglio, Mario. “L’esposizione romana di Depero.” Cronache d’attualità 1, 2 (March 1916): 2.

Cass Canfield, Mary. “The Passing of the Futurists.” Vanity Fair (April 1916): 69.

Chiesa, Laura. “Transnational Multimedia: Fortunato Depero’s Impressions of New York City (1928–1930).” California Italian Studies Journal 1, 2 (2010): 1–33.

Craft, Robert, ed. Igor Stravinsky: Selected Correspondence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982.

Crispolti, Enrico. “Le ‘nœud’ romain 1914/15: Balla, Depero, Prampolini et Boccioni.” Alfabeta. La Quinzaine littéraire 8, 84 (May 1986): 44–55.

Crispolti, Enrico. “Appunti su Depero ‘astrattista futurista’ romano.” In Depero, edited by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, 183–203. Milan: Electa, 1988. Exhibition catalogue.

Crispolti Enrico, and Maurizio Scudiero, eds. Balla, Depero: Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo. Modena: Galleria Fonte d’Abisso, 1989. Exhibition catalogue.

Depero, Fortunato. “Il teatro plastico Depero: Principi ed applicazioni.” Il Mondo 17, 27 (April 1919): 9–12.

Depero, Fortunato. Fortunato Depero nelle opera e nella vita. Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1940.

Depero, Fortunato. So I Think, So I Paint: Ideologies of an Italian Self-made Painter. Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1947.

Depero, Fortunato. “Appunti sul teatro.” In Fortunato Depero: Opere 1911–1930, edited by Bruno Passamani, 58–61. Turin: Galleria d’Arte Martano, 1969. Exhibition catalogue.

García-Márquez, Vicente. Massine: A Biography. London: Hern, 1995.

Kirby, Michael and Victoria Nes Kirby. Futurist Performance. New York: PAJ Publication, 1986.

Lerat, Pierre. “Les recherches futuristes.” SIC 17 (May 1917).

Pannaggi, Ivo and Vinicio Paladini. “Manifesto dell’arte meccanica futurista.” La nuova Lacerba 1 (June 1922); reprinted in Pannaggi e l’arte meccanica futurista, edited by Enrico Crispolti. Milan: Mazzotta, 1995.

Passamani, Bruno, ed. Fortunato Depero 1892–1960. Bassano del Grappa: Palazzo Sturm e Museo Civico, 1970. Exhibition catalogue.

Passamani, Bruno, ed. Depero e la scena: Da “Colori” alla scena mobile, 1916–1930. Torino: Martano, 1970.

Passamani, Bruno. Fortunato Depero. Rovereto: Musei Civici – Galleria Museo Depero, 1981. Exhibition catalogue.

Piconese, Barbara. Fortunato Depero dal futurismo italiano ai grattacieli di New York: Estetica multimediale ad alto livello comunicativo, thesis (Trieste: Università degli Studi, 2005).

Salaris, Claudia, ed. Fortunato Depero: Un futurista a New York. Montepulciano: Del Grifo, 1990.

Scudiero, Maurizio. Depero: L’uomo e l’artista. Rovereto: Egon, 2009.

Scudiero, Maurizio and David Leiber, eds. Depero a New York: Opere di Depero dalla mostra di Palazzo Grassi: Novembre futurista a Rovereto. Rovereto: La Grafica, 1986. Exhibition catalogue.

Scudiero, Maurizio and David Leiber, eds. Depero futurista, & New York: Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria. Rovereto: Longo, 1986. Exhibition catalogue.

Taylor, Christiana. Futurism: Politics, Painting and Performance. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1979.

“The Past and the Present of a Futurist.” Vanity Fair 36, 1 (March 1931): cover; 31.

Verdone, Mario. Avanguardie teatrali da Marinetti a Joppolo. Rome: Bulzoni, 1991.

How to cite

Günter Berghaus, “Fortunato Depero and the Theatre,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/fortunato-depero-and-the-theatre/, accessed [insert date].

- For more on Depero’s early years and artistic development see Bruno Passamani, Fortunato Depero, exh. cat. (Rovereto: Musei Civici – Galleria Museo Depero, 1981); and Maurizio Scudiero, Depero: L’uomo e l’artista (Rovereto: Egon, 2009).

- See Enrico Crispolti, “Appunti su Depero ‘astrattista futurista’ romano,” in Depero, ed. Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 1988), 183–203; and Enrico Crispolti, “Le ‘nœud’ romain 1914/15: Balla, Depero, Prampolini et Boccioni.” Alfabeta. La Quinzaine littéraire 8, 84 (May 1986): 44–55.

- For a detailed analysis of these performance see Günter Berghaus, Italian Futurist Theatre, 1909–1944 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 232–245.

- Umbro Apollonio, ed., Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973), 114.

- See the manuscript of 1914, Complessità plastica – Gioco libero futurista – L’essere vivente artificiale, printed in Passamani, Fortunato Depero, 39.

- Fortunato Depero, “Trascendentalismo fisico,” in Fortunato Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita (Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1940), 234.

- Foreword to the 1916 exhibition catalogue, reprinted in Fortunato Depero, Depero futurista (Milan: Dinamo-Azari, 1927), 116.

- Depero, Depero futurista, 116.

- Fortunato Depero, “Complesso plastico-mobile,” in Bruno Passamani, ed., Fortunato Depero 1892–1960, exh. cat. (Bassano del Grappa: Palazzo Sturm e Museo Civico, 1970), 158.

- Depero, “Complesso plastico-mobile,” in Passamani, Fortunato Depero, 156–157.

- Mario Broglio, “L’esposizione romana di Depero,” Cronache d’attualità 1, 2 (March 1916): 2.

- Printed in Bruno Passamani, ed., Depero e la scena: Da “Colori” alla scena mobile, 1916-1930 (Torino: Martano, 1970), 59. An English translation can be found in Michael Kirby and Victoria Nes Kirby, Futurist Performance (New York: PAJ Publication, 1986), 211; and Christiana Taylor, Futurism: Politics, Painting and Performance (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1979), 62.

- See Passamani, Depero e la scena, 59.

- Fortunato Depero, “Appunti sul teatro,” in Bruno Passamani, ed., Fortunato Depero: Opere 1911–1930, exh. cat. (Turin: Galleria d’Arte Martano, 1969), 58-61. It has been partly translated in Kirby, Futurist Performance, 207–210.

- See the reproductions in Carlo Belli and Bruno Passamani, eds., Depero, 1892–1960, exh. cat. (Spoleto: XXVI Festival dei due mondi, 1983), 46, 60.

- See the letter of March 13, 1917, in Robert Craft, ed., Igor Stravinsky: Selected Correspondence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), vol. 2, 141.

- Diaghilev apparently planned to show it in the next Paris season. Pierre Lerat announced in the Futurism issue of SIC (“Les recherches futurists” 17, May 1917): “Cet intérressant spectacle… sera donné à Paris dans le courant de mai ou juin.”

- Fortunato Depero, So I Think, So I Paint: Ideologies of an Italian Self-made Painter (Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1947), 58. A photograph of the garden and of some constructional designs for it have been published in Passamani, Fortunato Depero, 99; and in various Depero catalogues.

- Fortunato Depero, “Il teatro plastico Depero: Principi ed applicazioni,” Il Mondo 17, 27 (April 1919): 9–12; reprinted in Passamani, Fortunato Depero 1892–1960, 90–100.

- Quote from Passamani, Fortunato Depero 1892–1960, 147–151.

- Quote from Passamani, Fortunato Depero 1892–1960, 149.

- See the floor layout in Richard H. Axsom, Parade: Cubism as Theatre (New York: Garland, 1979), appendix 2, 239; based on the photograph in the Kochno Collection. The narrow space between the railing and the backdrop was not practicable, which meant that the three-dimensional managers acted against a quasi two-dimensional background.

- The texts have been printed in Passamani, Depero e la scena, 74–86. A facsimile of the manuscripts of three plays, which include the sketches for the stage designs, has been reproduced in Gabriella Belli, Nicoletta Boschiero, and Bruno Passamani, eds., Depero Magic Theatre, exh. cat. (London: The Italian Institute; Milan: Electa, 1989).

- See Fortunato Depero, “Mondo e il teatro plastico,” In penombra (April–May 1919), 20–22 and Fortunato Depero, “Il teatro plastico Depero: Principi ed applicazioni,” Il Mondo 17, 27 (April 1919): 9–12. Both essays were reprinted in Passamani, Depero e la scena, 95–97, 98–100.

- Ivo Pannaggi and Vinicio Paladini, “Manifesto dell’arte meccanica futurista,” La nuova Lacerba, no. 1 (June 1922); reprinted in Enrico Crispolti, ed., Pannaggi e l’arte meccanica futurista (Milan: Mazzotta, 1995), 178.

- See Berghaus, Italian Futurist Theatre, 1909–1944, 471–474.

- Fortunato Depero, “Parigi – Avanguardista e futurista (Auto intervista),” unpublished typescript (MART – Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto [from now MART]; Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero, Inv. no. 2909, 1–2). The long essay reports on theatre visits, Avant-garde cinema, meetings with Gleizes, Brancusi, Exter, Goncharova, Kiesler, Van Doesburg, Ozenfant, exhibitions of the Esprit Nouveau artists, and his own show, sponsored by Rolf de Maré, in the foyer of the Théâtre des Champs Elysées. See also Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita, 271–272; and Passamani, Fortunato Depero, 306.

- They have been printed in Passamani, Depero e la scena, 88–93.

- See the catalogues by Frederick Kiesler, ed., Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik im Rahmen des Musik- und Theaterfestes der Stadt Wien 1924: Katalog, Programm, Almanach (Wien: Kunsthandlung Würthle & Sohn, 1924); Frederick Kiesler and Jane Heap, eds., The International Theatre Exposition (New York: Little Review, 1926).

- See Claudia Salaris, ed., Fortunato Depero: Un futurista a New York (Montepulciano: Del Grifo, 1990); Maurizio Scudiero and David Leiber, eds., Depero a New York: Opere di Depero dalla mostra di Palazzo Grassi: Novembre futurista a Rovereto, exh. cat. (Rovereto: La Grafica, 1986); Maurizio Scudiero and David Leiber, eds., Depero futurista, & New York: Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria, exh. cat. (Rovereto: Longo, 1986); Barbara Piconese, Fortunato Depero dal futurismo italiano ai grattacieli di New York: Estetica multimediale ad alto livello comunicativo, thesis (Trieste: Università degli Studi, 2005); Laura Chiesa, “Transnational Multimedia: Fortunato Depero’s Impressions of New York City (1928–1930),” California Italian Studies Journal 1, 2 (2010): 1–33.

- Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 99–100, 126.

- See his letter to Marinetti of September 1929 in which he reports on a visit to a Variety theatre, “where a dance was performed over an electrified floor…. At every step, at every leap of the ultra-modern and agile dancers, one can see flashing coronas of phosphorescent light, followed by plays of shadows and light and vibrations of cinematic patterns. It was a Futurist picture of sensational accomplishment.” Enrico Crispolti and Maurizio Scudiero, eds., Balla, Depero: Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo, exh. cat. (Modena: Galleria Fonte d’Abisso, 1989), 142–147.

- Originally published in Fortunato Depero, Liriche radiofoniche of 1934, reprinted in Depero, Prose futuriste (Trento: VDTT, 1973); and Mario Verdone, Avanguardie teatrali da Marinetti a Joppolo (Rome: Bulzoni, 1991).

- See the chapter “Tè fascista inaugurale,” in Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 34–36; and Fortunato Depero, “I futuristi crearono lo splendore geometrico-meccanico” (MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero, ms. 6864).

- See Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 198–200; Passamani, Fortunato Depero, 228–230.

- Passamani, Fortunato Depero, 230.

- Quoted in Vicente García-Márquez, Massine: A Biography (London: Hern, 1995), 208.

- I trionfi di Depero nell’America del Nord” is the title of a 1929 article in an unidentified newspaper, preserved at MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero.

- The article in L’impero of August 8, 1929, is called, “Il futurismo negli Stati Uniti: L’opera di Depero esaltata dalla stampa americana: L’attività dell’artista a New York,” and contains a small paragraph on “Arte italiana di Wanamaker.” It formed part of a concerted effort to employ the Futurist success in Paris and New York for putting pressure on the Fascist government to have Futurism accepted as State art, to be given a national gallery for a permanent exhibition of Futurist art, and to oblige public galleries and museums to buy Futurist paintings and sculptures for their collections.

- “The Past and Present of a Futurist,” Vanity Fair (March 1931): 31.

- Mary Cass Canfield, “The Passing of the Futurists,” Vanity Fair (April 1916): 69.