Alberto Savinio: A Creative “Power Station”

Paola Italia Paola Italia Alberto Savinio, Issue 2, July 2019https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/alberto-savinio/

Wanderer of the imagination, alchemist of the word, and unable to give expression to his extraordinary creativity through one single art, Alberto Savinio left in his papers a precious testimony to his phenomenal intellect. In this essay, Paola Italia takes the reader on an exclusive journey into Savinio’s creative process, opening the doors of the writer’s archive (preserved in Historical Contemporary Archive “A. Bonsanti” at the Vieusseux Archive in Florence), sharing excerpts from his manuscripts, papers, and book drafts, and providing insight into not only Savinio’s working methods but also the secrets of his creativity.

I. Travel and Papers1

Until the age of forty, Alberto Savinio’s life was filled with continuous wandering, from city to city, “from music to music, from literature to literature.”2 Born in 1891 in Athens as Andrea Francesco Alberto de Chirico, he studied piano and composition in his youth, and later completed his musical training in Munich, with additional literary training in Milan (1906–08). He made his debut as a musician in Paris, where he had moved in 1910, as a writer in Ferrara (in 1915), and was sent in 1917 to the front in Thessaloniki. After the war, he joined literary circles in Milan and Rome, and moved back to Paris in 1926, where he stayed until 1932. His return to Italy (to Rome, that is) in the mid-thirties, marked the end of his travels and the start of his regular journalistic employment and literary activity.

Through those of Savinio’s papers that survived all this movement, it is possible to reconstruct his life’s work, for they provide a diary of his personal and artistic life. These many papers include published writings as well as others that remained only partially realized at his death. A wanderer of the imagination and an alchemist of language, unable to give expression to his extraordinary creativity through a single artform, Savinio, in his papers, provided precious testimony of his training, which was strongly interconnected with the birth of the so-called metaphysical school and the development of surrealism in Italy. His writings offer an extraordinary journey through the thinking of an eclectic and protean artist: a musician, narrator, essayist, and painter; an extraordinarily versatile figure who engaged with the Renaissance while actively participating in the restless experimentation of early twentieth-century Europe.3

Milan and Paris (1909–14): Savinio’s Debut

The oldest papers in Savinio’s archive, held in the Archivio Contemporaneo G. P. Vieusseux in Florence, date to 1909, when Andrea Alberto de Chirico was in Milan making visits to the Braidense National Library. There he read the Ancient Greek epic Argonautica, by Apollonius of Rhodes, and the fifteenth-century romantic epic Morgante Maggiore, by Luigi Pulci, possibly in preparation for a comic melodrama entitled “Poema fantastico,” now lost. In 1910, he moved to Paris (figure 1), where he worked on the tragicomedy “La nuit de la main morte” (The night of the dead hand, 1911); some ballets, including Deux amours dans la nuit (Two loves in the night, 1913); and the music for Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi’s libretto Le trésor de Rampsenit (The treasure of Rampsenit, 1911). He was friends with Guillaume Apollinaire, Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, and Jean Cocteau – all friends of Les soirées de Paris. In 1914, he published in that magazine “Le drame et la musique,” an avant-garde “manifesto” of musical “sincerism” (in which he called himself Alberto Savinio for the first time) and “Les chants de la mi-mort” (Songs of the half-dead), a theatrical script. For the latter, he also wrote music and painted sketches, now lost, of scenes and costumes. Over twenty years later, he translated these texts into Italian, indicating, in the sketches of the characters Bald Man and Yellow Man, the origins of metaphysical painting.

Ferrara and Thessaloniki (1915–18): The Works of the War4

When the First World War broke out, Savinio was enlisted as a soldier in the Italian army, as was his brother Giorgio, and sent to the city of Ferrara. There he developed his literary vocation, supported by his friends Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici, who helped him publish his first writings in the Florentine review La Voce. This world, which was far removed from that of his training, drew him into a sort of cultural “apprenticeship” through his reading of an eclectic assortment of publications in Italian – from grammar and style handbooks to the works of writers and poets including Giacomo Leopardi, whose Operette morali (The Moral Essays, 1827–35) Savinio used as a handbook to further improve his knowledge of the Italian language. His studies are recorded in numerous notes he took on the 27th Infantry Regiment, in which he served. In Ferrara, the “city of Worbas,” he saw the birth of his first and best-known novel, Hermaphrodito (1918), one of the most visionary and strange texts of the famous book series collection La Libreria della Voce (figure 2); it revolutionized literature, specifically the novel as a form. If Ferrara was a city of mystery, Thessaloniki, where Savinio was sent in July 1917, was a disturbing city. Despite the war, he continued to write stories once there, sometimes of an autobiographical nature, such as “Innocenzo Paleari” (written in 1918), and essays that he sent on an almost daily basis to his brother Giorgio. Only two letters have survived from their correspondence, written on the back of two texts sent in October 1917: “Dialogo con la mia giubba” (A talk with my jacket) and “Parallelo” (Parallel).

The First Postwar Period (1919–25): The Narrative Projects and the Letters

When Savinio returned to Italy from Macedonia at the end of 1918, he gave up on music and dedicated himself exclusively to literature. In this period, he wrote texts that would never be completed, such as “La statua pensante” (The thinking statue) and “Il pellegrino appassionato” (The passionate pilgrim) along with others he would publish only later, such as La casa ispirata (The inspired house, 1925; initially published in installments in 1920), which reconstructs his experience of Paris, and Tragedia dell’infanzia (Tragedy of Childhood; published in 1937), which recounts his childhood in Greece in a mythological and visionary key. The latter novel, one of his most beloved, has also a complex writing history, with much editing in its passage from manuscript to typescript to additional drafts. It was also followed by a second unfinished and unpublished part entitled “Sul dorso del centauro” (On the back of the centaur; written at the beginning of twenties),5 from which the author later retrieved some chapters for Infanzia di Nivasio Dolcemare (Childhood of Nivasio Dolcemare, 1941; figure 3).

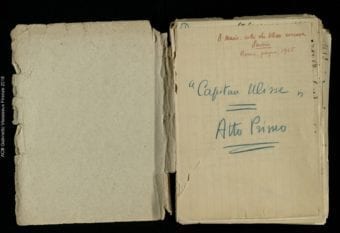

In 1923 he moved to Rome, and in 1925 began collaborating with Luigi Pirandello’s Teatro d’Arte, for whom – in the same year – he wrote Capitano Ulisse (Captain Ulysses), though he was unable to stage it. There, he met Maria Morino, who, along with her sister Jone, was part of the theatre company of Pirandello’s Teatro dell’Arte and to whom he sent some of the most beautiful love letters of the twentieth century, often accompanied by drawings. They married in 1926.

Determined to break free from his state of fils à maman, or immaturity, Savinio began contributing to the most important Italian artistic and literary magazines. Yet, while he was fairly engaged with these publications, it was always from the sidelines. He remained faithful to the artistic idea of a “real metaphysics” that he had developed since the Ferrara period, which his brother iconographically translated into paintings. The philosophical basis of such ideas he published in the magazine Valori plastici. Beginning in 1924, he wrote regular film reviews for Il Corriere Italiano, a newspaper founded in Rome in 1923 (in competition with Corriere della Sera; it closed in 1924 due to charges of criminal collusion with Giacomo Matteotti).

Paris (1926–33): Myths and Surrealism

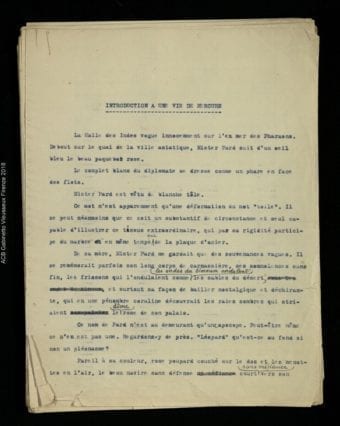

In 1926, Alberto and Maria Savinio moved to Paris, where Giorgio de Chirico was already established, having participated in the first issue of La Révolution surréaliste in 1924. Linked to this Parisian period are Angelica o la notte di Maggio (Angelica or the night of May; written in 1925 and published in 1927), Savinio’s closest novel to surrealistic poetics, and the Introduction à une vie de Mercure (Introduction to a life of Mercury, written in French in 1929 and only translated into Italian in 1990; figure 4) – the author’s most beloved and familiar “Goddess” (he would pursue its continuation, “The life of Mercury,” for years without ever completing it).

In 1940, André Breton included a statement in his introduction to the famous Anthologie de l’humour noir (Anthology of black humor) that recognized the de Chirico brothers as the original artists of the surrealist movement. In France, Savinio – who was beginning, in his turn, to paint – worked as a correspondent for Italian newspapers such as L’Ambrosiano and La Stampa, amusingly chronicling Parisian artistic life in pages later collected as Souvenirs (1945). In this way, he began to write a sort of “diary in public,” or a dialogue in absentia with his readers, which he continued over time in various newspapers and magazines.

Rome, the War (1933–46): Savinio as a Journalist

In 1933, Savinio undertook regular journalistic work back in Italy, including articles and reviews as well as literary, artistic, and musical texts resembling digressions or “reveries.” The variety of topics reflects the multiplicity of his interests and his extraordinary productivity. In twelve years, he published more than 1300 articles in publications of various kinds and political positions, from the monthly legal review I Rostri (where he reconstructed ten famous trials) to more fascist magazines such as Il Lavoro Fascista and Leo Longanesi’s Omnibus and L’Italiano. Omnibus was cancelled in 1939 by the fascist regime precisely because of an “irreverent” article by Savinio, in which he wrote that the great Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi had died of indigestion after eating sorbet. At the time, it was impossible to write such irreverent things.6 At the end of 1933, with funding from the industrial brewer Peroni, Savinio founded and oversaw the monthly Colonna, but its publication was suspended in April 1934 after only five issues. As of 1946, at the invitation of the director Mario Borsa, he contributed regularly to the most important Italian newspapers, Corriere della Sera and Corriere d’Informazione, which helped consolidate his fame and the interest of his growing population of readers (figure 5).

II. A Creative “Power Station”

Savinio’s literary and nonfiction production of the forties reflects a decade of magnificent and extraordinary creative success, stimulated by his highly fruitful sponsorship by Valentino Bompiani, who became his only publisher as of 1942. Countless projects came out of this relationship, some of which were published only posthumously, such as Nuova enciclopedia (New encyclopedia; 1977). In these years Savinio dedicated himself to the organic collection of his already widely published works and sent some of his most famous books to print, from Infanzia di Nivasio Dolcemare to Narrate, uomini, la vostra storia (Tell, men, your own story, 1942). Savinio was indeed a “creative power station,” as he used to call himself. In addition to his musical, narrative, and dramaturgical activities, he was making paintings. He translated them into theatrical form as set designs and sketches of figurines of his and others’ works, and introduced them into literature as illustrations and covers for his books. Savinio settled in Rome, where he remained until his sudden death on May 5, 1952, while he was attending rehearsals for one of his last efforts, the staging of Gioachino Rossini’s opera Armida for the Florentine Musical May.

The notes, drafts, and manuscripts held in Savinio’s archive reveal the gears and principles of construction behind his works, just as they do his intentions for the toys of life: life is an island of toys where the “ulisside man” lands and stops to understand, through the mechanism of reality, the mechanism of thought.

Biographies and Travel Books: From Infanzia di Nivasio Dolcemare to Dico a te, Clio

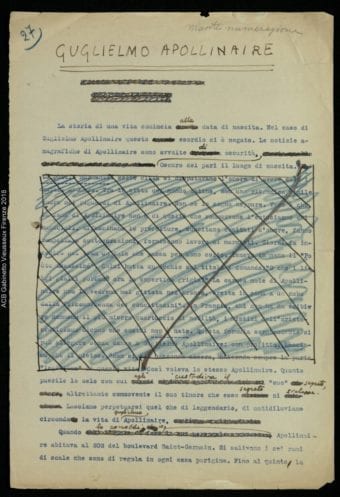

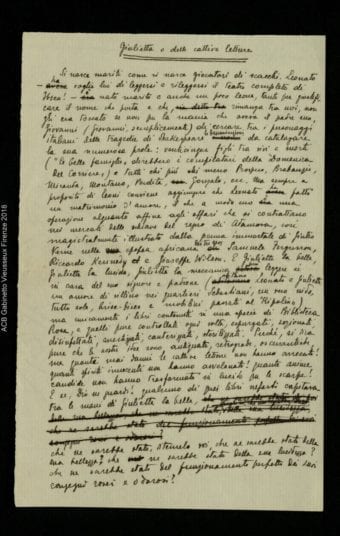

Savinio’s narration of history in fantastical, romantic forms is at the same time an overcoming of history, of “mobile and transitory” reality, in an effort to enter the “still and lasting” art world. From his autobiographical Infanzia di Nivasio Dolcemare, an imaginative memoir of his childhood in Greece, to his biographies of famous (and not so famous) men, among them Apollinaire (Narrate, uomini, la vostra storia; figure 6), Henrik Ibsen (Vita di Enrico Ibsen [Life of Henrik Ibsen], 1979), and Guy de Maupassant (the reconstruction of his life entitled Maupassant e “l’altro,” [Maupassant and “the other”], published in 1975), Savinio unscrupulously delved into the lives of others, reading into “all their physical and metaphysical essence” to depict them as “pitiful and terrible.” Elsewhere, his writings based on reports written for newspapers are faithful to his destiny as a “passionate pilgrim;” these travel notes are collected in small jewels such as Dico a te, Clio (Speaking to Clio, 1939).

The Essays: From Ascolto il tuo cuore, città to Nuova enciclopedia

The volumes of essays from the forties systematically collect Savinio’s journalistic output from the previous decade and were the first to be favorably received by readers. Ascolto il tuo cuore, città (Listening to your heart, city, 1943) was written shortly before Milan was devastated by bombing in the Second World War; it is dedicated to that city. Savinio considered the book to be one of his dearest successes, and had not wanted to publish it during the war for fear of errors caused by terribly difficult conditions. It analytically documents itself from first draft to final phase of printing, including letters exchanged with Valentino Bompiani. The war is also reflected in Sorte dell’Europa (The destiny of Europe, published in 1945); this is the most committed of Savinio’s nonfiction works, composed when “in Italy it was possible to write about political things again.”7 The materials of the Nuova enciclopedia make it possible to enter the laboratory of Savinio’s most enlightened and “Volterian” book, which, renouncing the “homogeneity of ideas,” strives “to make the most desperate ideas live together in a less bloody way, including the most desperate ideas.”8 The original manuscript is in Savinio’s archive, and as the summa of the author’s eclecticism, it contains preparatory indexes and some items not included in the edition released posthumously by the publishing house Adelphi in 1977.

The Short Stories: From Achille innamorato to Tutta la vita

Represented effectively by his dreamlike and visionary paintings, Savinio’s short stories are perhaps among only a few examples of “fantastical” fiction in twentieth-century Italian literature. While Achille innamorato (Gradus ad Parnassum) (Achilles in love (The steps to Parnassum), 1938; figure 7), his earliest collection, displays all the nuances of his expressive palette, from memorial narrative to first representations of myth and bourgeois environments, the volumes from the forties – Casa “la Vita” (Home “The Life”, 1943), La nostra anima (Our soul, 1944), and Tutta la vita (A whole life, 1945) – assume apparently ironic forms and distract from undeniable ghosts of the unconscious. This is not the literature of surrealism, aimed at representing the unconscious, but rather a “real metaphysics,” which gives “form to the shapeless and consciousness to the unconscious.”9

In La famiglia Mastinu (The Mastinu family), on the other hand, a collection of stories, Savinio put together in 1948 for a literary prize (eventually, he would be awarded the Re degli amici, but in 1949 for Alcesti di Samuele (Alcestis, daughter of Samuel), we witness the “passage of witness” from narrative to theater, for the text that gives the volume its title (published only posthumously) appeared in both narrative and theatrical versions, once again subverting traditional literary canons.

Theater and Music: From La morte di Niobe to Vita dell’uomo

The theater – “a reflection on the scene of the condition of the universe”10 – was the writer’s first and last passion, and perhaps the means through which he could best express his peculiar “civil” conception of literature and art in general. Savinio began his work in theatrical production in 1912 with musical dramas prepared in Paris, and returned to it, in both musical and prose terms, in the last period of his life, with famous, unique acts such as Alcesti di Samuele and Emma B. vedova Giocasta (Emma B. Widow Giocasta, 1949). Two other such works – La famiglia Mastinu and Il suo nome (His name, 1945) – he derived (according to the Pirandellian model) from short stories. In this period, he also produced the ballet Vita dell’uomo (Men’s life; written in 1946), the one-act opera Orfeo vedovo (Orfeo widowed, 1950), and the radio opera Agenzia Fix (Fix agency, 1951). Between these two extremes, there was an intermediate “landing” that links to Savinio’s frequenting, around 1925, Pirandello’s Teatro d’Arte, evident in La morte di Niobe (The death of Niobe) and Capitano Ulisse (written in 1925, published in 1934, and first staged in 1938; figure 8). Equally interesting are his theater reviews published in 1937 and 1938 in Omnibus, later collected in Palchetti Romani (Roman box seats, 1982).

The “Mechanical Dream:” Film Reviews and Projects

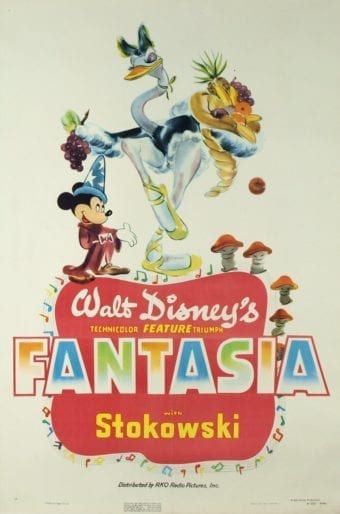

Always ahead of his time, Savinio grasped the expressive potential of cinema. He saw it as the most suitable instrument for realizing his idea of an art aimed not at objectively reproducing reality, but at discovering mystery and translating it into fixed, lasting form. “The ‘cinematographer,’” he wrote in 1924, “constitutes a justification for art as innocent and coarse as it is, for the art we have always understood and advocated: art not as a direct mirror of reality, but as a distant and mnemonic reflection of that.”11 Savinio was also the first journalist to write a film review in an Italian newspaper, and from 1922 to 1924, in Corriere Italiano, he published daily reviews of famous masterpieces such as Paul Weneger’s Der Golem (The Golem, 1915) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid (1921), as well as forgotten films such as Mario Bonnard’s I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1923). In the thirties and forties, as he continued to regularly write about cinema in various newspapers – reviewing, for example, Disney’s Fantasia (1940; figure 9) – he wrote film scripts that would never be shot, such as “Didone abbandonata” (Abandoned Dido; published in Documento in 1942) and, in 1945, the story of the life of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Bibliography

Italia, Paola. Il pellegrino appassionato. Savinio scrittore (1915–1925). Palermo: Sellerio, 2004.

Italia, Paola, ed. Le carte di Alberto Savinio. Mostra documentaria del Fondo Savinio. Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, 1999. Exhibition catalogue.

Savinio, Alberto. “Rivista del cinematografo,” Galleria 1, no. 1 (January 1924): 55.

Savinio, Alberto. Casa “la Vita” e altri racconti. Edited by Alessandro Tinterri and Paola Italia. Milan: Adelphi, 1999.

Savinio, Alberto. Hermaphrodito e altri romanzi. Edited by Alessandro Tinterri. Milan: Adelphi, 1995.

Savinio, Alberto. Nuova enciclopedia. Milan: Adelphi, 1977.

Savinio, Alberto. Scritti dispersi (1943–1952). Edited by Paola Italia. Milan: Adelphi, 2004.

Savinio, Alberto. Sorte dell’Europa. Milan: Adelphi, 1977 (first published in 1945).

How to cite

Paola Italia, “Alberto Savinio: A Creative ‘Power Station’,” in Alberto Savinio, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 2 (July 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alberto-savinio-a-creative-power-station/, accessed [insert date].

- I would like to thank Alberto Savinio’s heirs, and expecially Ruggero Savinio, for allowing me to present, through the images of the family archive, the laboratory of Savinio’s “power station.” I am also grateful to Gloria Manghetti, director of the Archivio Contemporaneo A. Bonsanti, for having facilitated my research and provided access to Savinio’s papers.

- In his review of Savinio’s Hermaphrodito, Giovanni Papini wrote: “Tu non vorresti, forse, ch’io rivelassi il tuo passato di passionate pilgrim dalla Grecia all’Italia, dall’Italia alla Baviera, dalla Baviera a Parigi, di musica in musica, di letteratura in letteratura” (La vraie Italie, April 1919). All translations are mine.

- For a more detailed account of the editorial history of Savinio’s works, see the Adelphi editions of his oeuvre, edited by Alessandro Tinterri and myself (Hermaphrodito e altri romanzi [1995]; Casa “la Vita” e altri racconti [1999]; and Scritti dispersi (1943–1952) [2004]).

- On these years specifically, see Paola Italia, Il pellegrino appassionato. Savinio scrittore (1915–1925) (Palermo: Sellerio, 2004).

- I had the opportunity to republish Tragedia dell’infanzia (Milan: Adelphi, 2001) with the previously unpublished “Sul dorso del centaturo” as an appendix.

- Savinio’s article “Leopardi’s Sorbet” was published on January 28, 1939.

- In the preface of Sorte dell’Europa Savinio wrote: “Raccolgo in questo libretto gli scritti di carattere politico da me pubblicati tra il 25 luglio e l’8 settembre, ossia quando in Italia si ricominciò a poter scrivere anche di cose politiche.” Alberto Savinio, Sorte dell’Europa (Milan: Adelphi, 1977), 3.

- “Rinunciamo dunque a un ritorno alla omogeneità delle idee, ossia a un tipo passato di civiltà, e adoperiamoci a far convivere nella maniera meno cruenta le idee più disparate, ivi comprese le idee più disperate.” Alberto Savinio, Nuova enciclopedia (Milan: Adelphi, 1977), 133.

- This is the passage in the preface of Tutta la vita: “Quanto a un surrealismo mio, se di surrealismo è il caso di parlare, […] non si contenta di rappresentare l’informe e di esprimere l’incosciente, ma vuole dare forma all’informe e coscienza all’incosciente.” Alberto Savinio, Casa “la Vita” e altri racconti (Milan: Adelphi, 1999), 555.

- This definition (“Il riflesso sulla scena della condizione dell’universo”) can be found in Savinio, Nuova enciclopedia, 361.

- “Il ‘cinematografo’ anzitutto costituisce una giustificazione per quanto innocente e grossolana, dell’arte quale noi l’abbiamo sempre intesa e propugnata: l’arte non come specchio diretto della realtà, ma come riflesso lontano e mnemonico di quella.” Alberto Savinio, “Rivista del cinematografo,” Galleria 1, no. 1 (January 1924): 55.