A Path à rebours for Marino Marini’s Wooden Nudo femminile of 1936–41

Gianmarco Russo Gianmarco Russo Marino Marini, Issue 5, May 2021https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/marino-marini/

In 1939, in one of his best-known statements, Marino Marini juxtaposed life-size female nudes with portraiture. Compared to portraiture, the sculptor wrote, “the statue requires a vaster research into forms, lines, masses. My women, whom some find clumsy, are an answer to this concern. Nevertheless, this search for volumes is not the unique purpose of the sculptor, who must never forget that what touches most in a sculpture is always its poetry.” This paper elaborates on Marini’s female nudes of the late thirties and forties in light of the relationship between form and poetry, or in other words, between the plastic construction of volumes and the expressive power of surfaces. Firstly, it discusses the fracture between form and modeling, volumes and profiles, plastic development and surface definition, tracing a path à rebours from the Danzatrice (Dancer) of 1949 now at MoMA in New York to the Maschera (Mask) of 1936 at the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia. Secondly, it offers an examination of Marino’s wooden Nudo femminile (Female nude) traditionally dated to 1932, showing a mechanical dependency between the latter and the 1936 statue, and fixing the chronology between 1936 and 1941.

With vague reference to the French post-Rodin avant-garde, from Degas to Picasso, Marino Marini often introduced the world of theater into the noble theme of the female nude, which he explored at various moments in his artistic career of statues, drawings, and paintings. At the exhibition held at CIMA last year, there were two sculptural examples of this subject: both in bronze, one small; the other larger than natural. The first, which had come from the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia, was one of the three casts of the Piccola danzatrice (Small dancer) of 1944 (figure 1); the second, kept in New York at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and also one of three existing examples, is the imposing Danzatrice of 1949 (figure 2).1

Despite the varying formats, different conceptions of the poses, and diverse interpretations of the supports, these works nonetheless have a common subject. The Piccola danzatrice, in comparison to the more balanced and defined shifts of Marini’s previous works, betrays a disjointed geometry of dilated and sharp forms. The oval shape of the ballerina’s left foot, perhaps to be imagined with a pointe shoe on, is repeated in the legs and breasts (figure 3). This was Marini’s unique way of transferring the large volumes of the Mediterranean figures painted by Pablo Picasso in the twenties into sculpture, which had been a constant point of reference in defining the expressionless and out-of-time heads of his female nudes between 1938 and 1940.2 Only hinted at in the Pomona sdraiata (Reclining Pomona)3 of 1938–41 (figure 4), and taking part in the controversy against Aristide Maillol’s cold classicism, the eccentric modeling of the Piccola danzatrice evokes the vital fullness of prehistoric statuettes, adding a naturalistic component to the abstract sketch of the woman’s anatomy and creating a disturbing short-circuit between the modernity of the subject and the archaism of the form.

The following year, Marini continued this type of research in his Piccolo nudo (Small nude) of 1945, documented in the CIMA exhibition by a wonderful cast from the Cincinnati Art Museum,4 in which the concept of the body raped by war is combined with the mysterious reclined posture of an ancient Chinese idol.

A further step forward was on view in two figures whose Mediterranean inspiration is evident, both in the geometric sense of Picasso’s painting and in the abstract sense of the Cycladic civilization: the Nudo of 1947 (figure 5) and the Piccola Pomona (Small Pomona) of 1949 (figure 6).5 In these works, Marini contended with an alien and ahistorical format, 80 centimeters in height (31 1/2 inches), which brought his latest female figures closer to the architectural logic of the Cavalieri (Riders) of the two-year period between 1945 and 1947.6 Significantly, in this series Picasso’s example is even more clearly legible thanks to the obvious reference to Guernica’s downed horse and its tragic lyricism.

The female nudes mentioned so far allow us to clarify the path that led Marino Marini from the Piccola danzatrice of 1945 to the Ballerina of 1949. The tappings on the forehead, left arm, breasts and legs of the former, obviously obtained by the artist on the plaster model, bring the treatment of the sculptural film closer to that of painting. As Laura Mattioli generously pointed out to me during my first visit to the exhibition, the same indentations can be seen on the Figura of 1947 and the Piccola Pomona of 1949.

In the big Danzatrice at MoMA, the modern world of theater absorbs the nude’s apparently academic subject without sacrificing pure form and absolute plasticity in the name of content. Here, the pictorial interpretation of the surface finds its highest expression, coloring itself with different finishings, performed not on the plaster model but on the final bronze (rifiniture a freddo). The morphological and compositional definition of these details call for technical analyses that would allow us to simultaneously investigate the mechanical and chemical treatments of the metal of Marini’s sculptures. In the 1949 Danzatrice, traces for this type of research would be provided by the greenish patina that accompanies the rhomboid design on the ballerina’s outfit and gives the work the appearance of a wreck saved from the ocean, still covered in moss.

The two Danzatrici – the small and the large – demonstrate how, in the years coinciding with or following the Second World War (when Marini moved to Tenero, Switzerland, near Locarno), the dance and theatrical subject of these sculptures was nothing more than a pretext to explore the articulated architectural interlocking of forms and its divorce from the purely pictorial reasons of the surface. In the smaller statue, the theme is not easily recognizable. Hinted at in the larger Danzatrice’s slightly spread legs is the request that the viewer look more closely, which is quite difficult and not immediately satisfying since the rhomboids in the dress, the ring of the left hand, and the necklace are not directly attributable to the ballet world. In the Danzatrice at MoMA, these details take on the meaning they would have in any other series by Marini: they are fragments of a lived reality that loosen the form’s overall abstract transfiguration, introducing a naturalistic gaze, sometimes pungent when not disturbing.

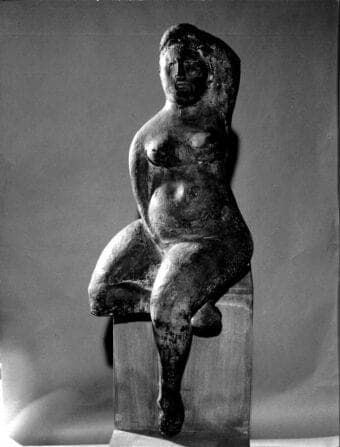

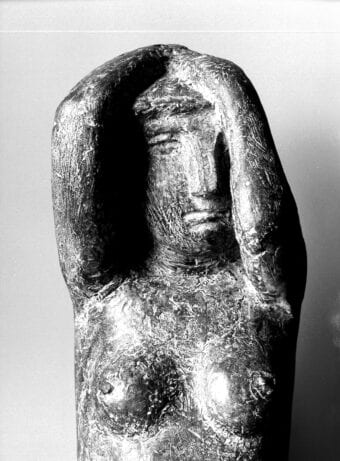

This relationship between form and content, more complexly stated by Marini as tension between “composition” and “poetry”7 in 1939, is far more fleeting in another Danzatrice that is generically said to be dated to an abrupt 1945 (figure 7). I am referring to a plaster model preserved in a fragmentary state at the Fondazione Marino Marini.8 If it were not for the caption of figure 61 in Raffaele Carrieri’s 1948 monographic study of Marini,9 one would not be able to immediately identify a dancer in this figure. Once recognized, other than the structure of Marini’s most acclaimed female nudes from previous years (think, for example, of the Giovinette [Young ladies] of 1938, 1939, and 1940, or of the contemporaneous Venere [Venus]),10 one can glimpse the movements of a dancer in the woman’s decentralized position in relation to the pedestal. The latter has the task of making the work a real statue and of pointing this out to the viewer already enchanted by the firmness of the legs, the fleshiness of the belly, and the naturalness of the breasts raised up by the gesture of the arms around the head. The large amount of plaster confusedly modeled in the upper part of the work hides the face and arms, urging the viewer to focus on the story of the orchestration of the bodily shapes and the graphic and chromatic accidents on the surface.

These are the same poetic intentions that sometimes pushed Marini to devise blank and inexpressive faces for his women (for example, in the 1938 Giovinetta) or, more frequently, to cut off heads and arms (as in the 1941 Pomona).11 In this way, the sculptor could subtract from his work the parts of the body most clearly designated by the academic tradition as the sites of dialogue and narration. In the Danzatrice of 1945, he did this by alluding to Michelangelo’s non finito sculptures, following Auguste Rodin’s treatment of matter as imprisoned in form, without the possibility of escaping from it. Not surprisingly, in this moment the revival of the French master’s poetics in an expressive key intensifies,12 and through it Marini was able to return to the ancient masters (Michelangelo, but also Donatello) as an affirmation of his self-awareness as a sculptor belonging to a lineage of great artists.

To limit the discussion only to the examples of female nudes, this is evident in the passage from the Piccole Pomone of 1943 (figure 8) and 194413 to the contemporary bas-reliefs Composizione and Le tre grazie (The Three Graces)14 to the 1945 Danzatrice. Both in the statuettes and in the panels, the faces lack any physical resemblance to the point of becoming, in some cases, devoid of any physiognomic detail. The third woman on the right in Composizione is, in this respect, significant, with her left arm bent and resting on her hips just like in the defiant attitudes of the Renaissance heroes (Verrocchio, Donatello), along with the Piccola Pomona of 1944 (figure 9), where the tragic gesture of bringing one’s arms over the face to cover one’s eyes from the horrors of war meets up with the pure construction of forms, outside of any anecdotal and narrative vein.

In one of the three 1943 figures – the one with the arm behind her back – Marini reduced the eyes and nose to very light marks that confuse themselves within the superficial ripples of the modeling. Thus, he only emphasized the study of the figure’s internal syntax; and, significantly deviating from the rest of his oeuvre, the sculpture has an unexpected permeation between plastic development and epidermal definition. This unpredictable overlap between form and modeling seems to occur only in the three 1943 statuettes and in the bas-reliefs of the same year; namely, in works strongly inspired by a pictorial vision in which the sculptor’s touch, who modeled these figures in terracotta by adding material, is still perceivable despite the bronze cast.

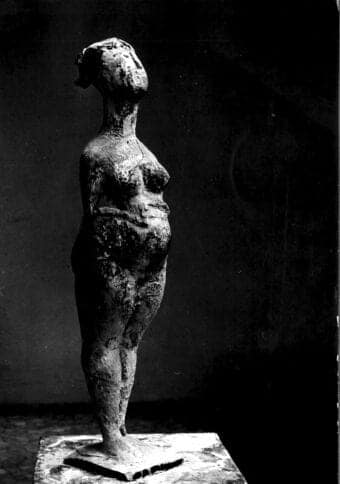

The path traced by the Piccole Pomone and the sculpted panels constituted a minor aspect of Marini’s research in the field of the female nude. At the same time, he was creating works very different from the previous ones, in which the balancing of volumes tends to have the effect of humanistic monumentality while colliding with the bright enchantment of the sculptural skin. I am referring to the female nudes of Marini’s Swiss period, such as the Giovinetta (figure 10) and the Bagnante (Bather) of 1943 and the Pomona of 1945.15They open a rift not only between each other and the contemporary Piccole Pomone, but even more so between each other and the figures Marini was producing up to that point.16

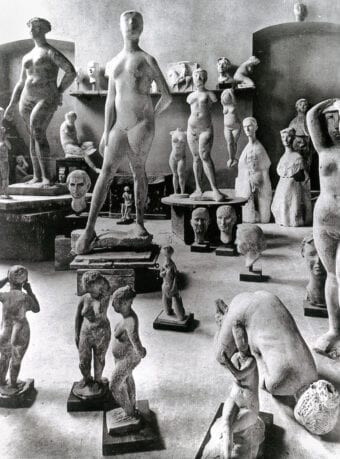

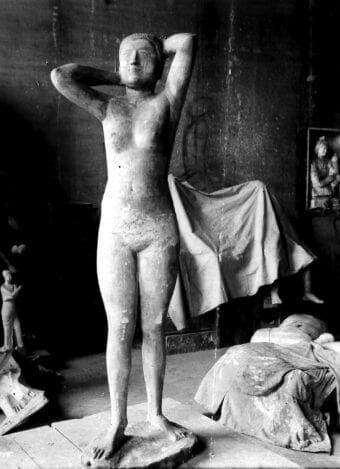

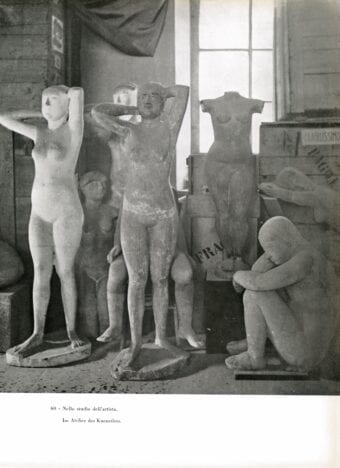

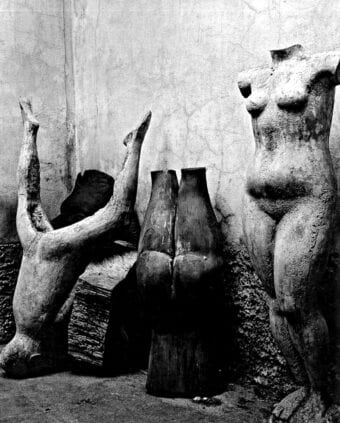

This profound otherness is illustrated by the magnificent photographic view of Marini’s studio in Locarno taken in 1945 by Fritz Wotruba (figure 11), a friend and colleague of the Italian sculptor who was also living in Switzerland (Figure ). In the foreground, the Piccole Pomone only seem to offer themselves as experiments in articulated poses. The rough and incandescent treatment of the modeling, which in those same years led Gianfranco Contini to compare Marini to a “poet of surfaces,”17 almost makes them shine in their own light. In the background, the 1943 Giovinetta, despite the absence of the arms cut immediately under the deltoids – as in glorious ancient busts – is distinguished from a headless nude (on the left) and the 1945 Danzatrice (on the right) through the compass-like opening of the legs and the head’s inclination, which returns in one of Marini’s figures after the Pomona of 1941 and the Venere of 1942,18 correctly interpreted by the Italian critics at the time as pure “plastic waves”19 or abstract “trunks of cone.”20

In the photograph by Wotruba, between the Piccole Pomone and the Giovinetta, among several other works of various subjects, the Bagnante of 1943 (figure 12) and the Pomona of 1945 (figure 13) stand out. With these last works, Marini specified his interests in the great ancient masters (especially Donatello)21 and his preoccupations with a more expressive humanity through the complication of the compositions, the use of the contrapposto, and multiple points of view.

The figure standing on the right in the photograph, a Pomona with raised arms reproduced in Contini’s 1944 booklet,22 represents the bridge between the Giovinetta of 1943 and the Pomona of 1945; its verticalism’s tendency toward abstraction brings it closer to the former, while it is more in tune with the latter through the expressive strength of the face. This animation is not achieved through naturalistic verisimilitude, but through a precise calculation of the geometric interlocking between the volumes of the arms and head, which favor a suffused and intriguing play of light and shadow (figure 14). Moreover, the powerful squaring of the nose suggests that Marino was reflecting on the female heads sculpted by Picasso in the early thirties and on works made in those same years by Henry Moore. In fact, the proud face of the Bagnante of 1943 or the terrified face of the Figura seduta (Seated figure) of the following year23 are better understood in light of some of the British master’s examples from the late twenties.

The Pomona of 1944 and the Danzatrice of 1945 propose the same framework of the female nude with the arms raised to the head. As we have seen, in them Marini canceled, in a different way, the anatomical complexity of the woman’s face and arms to give back only the story of the interaction between the architecture of the volumes and the poetry of the surfaces.

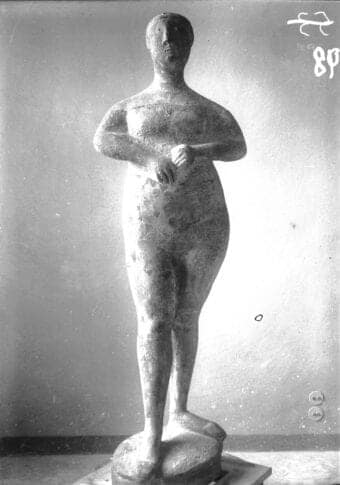

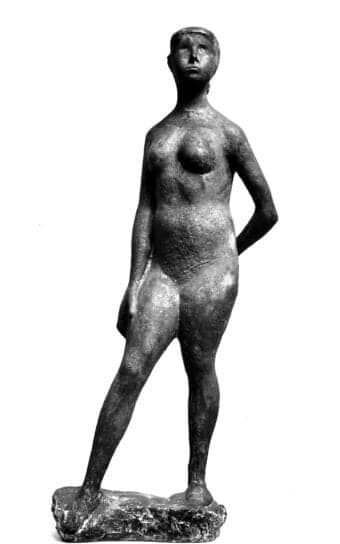

A few years earlier, he had already experimented with this variation of the female nude in a 1940 terracotta,24 in which the relationship between the face’s universality – outside the here and now – and the body’s individuality – enhanced by the medium of ancient Etruscan memory – is the same that takes shape in the Pomona with the arms behind the back that sold in the same year to Emilio Jesi, one of Marini’s most loyal collectors.25 Another nude with raised arms dates back to 1939 (figure 15) and was documented two years later in the Simonotti collection in Milan; a unique bronze specimen, it shuns the academic misunderstanding of the pose in part through its medium format, at 135 centimeters in height (53 inches),26 which was next applied for the 1943 Giovinetta.

However, Marini’s most interesting female figure to be characterized by this arrangement of the arms can be dated to the mid-thirties. It also constitutes the first example of the thematic interference of the nude and theater in Marini’s work. Generally believed to be from 1932, and published with this date in the sculptor’s catalogue raisonné,27 it was actually conceived around 1936.

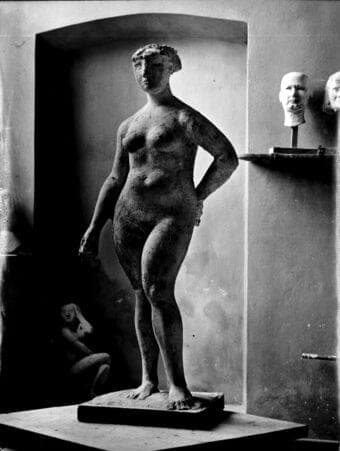

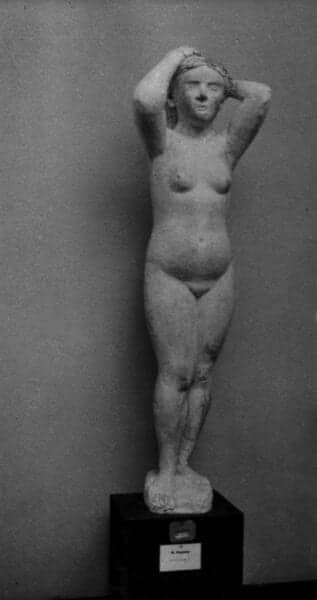

Not by chance, that same year the figure’s plaster preparation was exhibited by the artist at the Venice Biennale with eight other works, among which the first Cavallo e cavaliere (Horse and rider) of Marino’s oeuvre stood out.28 The importance of this occasion for the development of the master’s sculptural research is easily understood. While all the critics condemned the merciless abstraction and sinister primitivism of that “equestrian Mamluk,”29 the authoritative voice of the acclaimed painter Carlo Carrà celebrated the “formal balance” and “curious realism” of the last nude mentioned.30 He referred to this work entitled Maschera (Mask), for it clearly represented a young woman with her arms raised and her hands behind her head in the attempt to put on or take off a mask (figure 16).

Compared to all the themes within which Marini interpreted the female nude subject, this is undoubtedly the most mysterious and disturbing. Even Pomona’s tale, like Venus’s, could better marry the aesthetic meanings of its creation thanks to the link that the ancient pre-Italic deity of fruitful abundance had with Etruscan tradition. Studying the Maschera in relation to Marino’s oeuvre allows us to attune this sophisticated intellectualism to some slightly earlier works, informed by an idea of sculpture still close to Arturo Martini’s sensual anecdotal reenactments, first of all the Bagnante of 1934, exhibited at the Second Quadriennale in Rome in 1935.

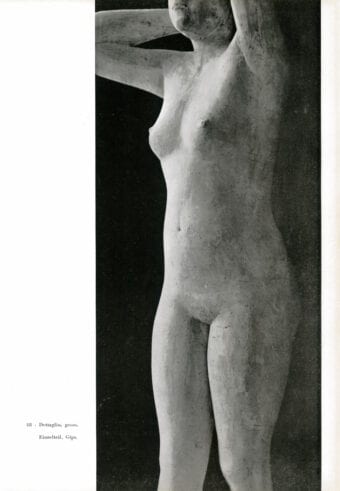

The title Maschera is not found in any of the publications covering the chronological period in question. In a booklet edited by Lamberto Vitali in 1937 for the Italian Modern Art series by Giovanni Scheiwiller, the caption of the work’s photograph reads “Giovinetta.”31 In the 1941 volume prefaced by Filippo de Pisis, three reproductions of the statue are present. Two are not mentioned in the caption because one is in the background of the 1928 Vittoria in stone(figure 17),32 and the other is replicated in various plaster casts in the artist’s studio in Monza (figure 18).33 Under the third image (figure 19), previously published by Vitali, we simply read “Detail, plaster.”34 In Carrieri’s book for Edizioni del Milione (1948), the figure is accompanied by the words “Nude – 1935 (detail).”35 Nudo con la maschera (Nude with the mask), or more simply Maschera, exhibited by Marini at the 1936 Biennale, perhaps already made the previous year (as underlined by the image published by Carrieri), was baptized with various titles that swept away the subject’s impenetrable meaning and reduced it to a more approachable Giovinetta (1937) or a purer detail (1941) of any female nude (1948).

The absence of the title Maschera in the three mentioned captions explains the decisive close-up made of the 1935–36 statue. This is the official historical photograph of Marini’s work, and the young woman is captured from her mouth to her knees. She thus appears deprived of most of her arms and face, and her head and upper limbs are mutilated, as in the great nudes made by the sculptor in the season between 1938 and 1942, or in the Danzatrice of 1945. The history of the ways of photographing Marini’s works in the thirties and forties leads us to consider the possibility of a real collaboration between the artist and the photographer,36 even in the critical and iconographic resemantization of the Maschera in the years following 1937. It is believable that in 1936 Marini conceived a work in a puzzling narrative vein, immersed in a magical suspension between realism and abstraction. Once the main preoccupations of his profession as sculptor were clarified in the 1936 Venice Biennale, he had to reinterpret this work of the past as a clear development of forms in space and sophisticated graphic refraction in the environment, according to what he had developed starting from the Giovinetta exhibited at the 1939 Roman Quadriennale.37

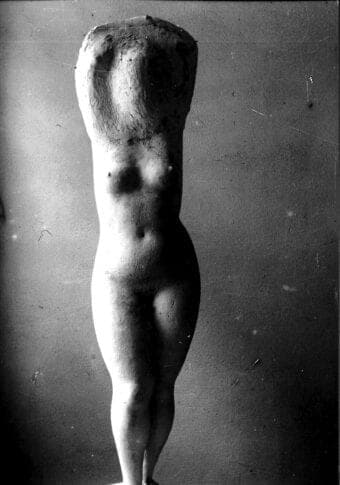

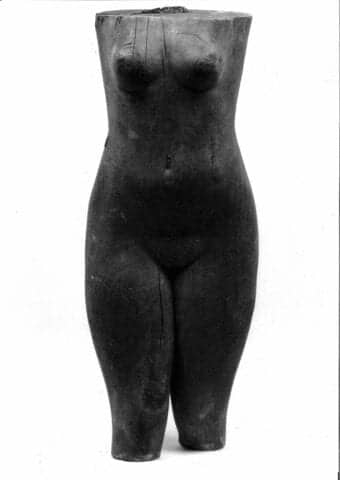

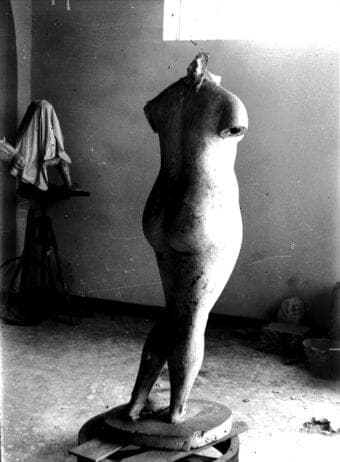

This order of problems leads me to consider the wooden Nudo femminile kept at the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia (figure 20) and lent to the 2019–20 CIMA exhibition,38 which speaks to the material product of the refinement of the sculptor’s aesthetic and poetic tools between the end of the thirties and the beginning of the forties. The Maschera’s cropped photograph was first published by Vitali and then by de Pisis and can in fact be considered the critical suggestion for obtaining a totally renewed and far more modern work from the ancient prototype, thus moving from a work with indefinite narrative outlines to one of pure formal interrogation.

The mechanical process through which Marini obtained the new nude illustrates this transition. At first, he had to make a hollow mold in the initial wooden model in which to cast the plaster to be exhibited at the Venice Biennale. It has not been established when the master was able to saw the wooden prototype from the chest up and the knees down, but I suspect this took place around 1941 – namely, after the publication of de Pisis’s book and the mutilation of the Pomona sdraiata’s arms.39 The measurements of the wooden fragments of the Maschera practically coincide with those of the plaster work,40 reassuring us on the mechanical dependency between the pieces.

The result is a dramatically mutilated female nude or, if one prefers, a severe architectural volume vaguely reminiscent of a female nude. The use of wood, an anti-academic and avant-garde material par excellence, allowed Marini not only to visually emphasize the gesture of the cut (evenly cut only in the upper part, but not leveled at the knees), but also to impart a soft and sensual touch to the coldness of the operation: the grain of the wood, along with the cracks opened over time, almost seems to evoke the wrinkles and roughness of the skin of a real female body, relating the surface of the work to a sort of geographical map requiring slow and contemplative reading.

The stunning photographic image made by Herbert List in Marini’s studio in Milan in 1950 (figure 21) encourages this interpretation.41 In fact, the photograph immortalizes the wooden nude upside down against a wall with a double layer of plaster (one left rough, the other finished) and invites us not only to linger on the suggestive tactile potential of the materials, but also on the infinite possibilities of how the work might be positioned. In CIMA’s important exhibition, one could have imagined admiring this masterpiece upside down, as in List’s photograph. On this imaginary path, one could then envision the Pomona of 1941, exhibited on her back, as in the various historical shots (figure 22) that—to this day—still help us study and understand the nuances of Marino Marini’s female nudes.

Bibliography

XX Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Catalogo. Venice: Ferrari, 1936. Exhibition catalogue.

Carandente, Giovanni, ed. Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura. Milan: Skira, 1998.

Carrà, Carlo. “Scultori italiani e stranieri alla XX Biennale di Venezia.” L’Ambrosiano, August 1, 1936.

Carrieri, Raffaele. Marino Marini. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1948.

Contini, Gianfranco. Vingt Sculptures de Marino Marini présentées par Gianfranco Contini. Lugano: Quaderni della Collana di Lugano, 1944.

Fabi, Chiara. “Cavalli e Cavalieri.” In Marino Marini. Passioni visive, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi, 172–89. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Fotografare (e pubblicare) le sculture. Un antefatto anni trenta-quaranta per Marino e Manzù.” In Manzù/Marino. Gil ultimi moderni, edited by Laura D’Angelo and Stefano Roffi, 45–61. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Prima della fama internazionale. Temi della ricerca scultorea di Marino Marini tra gli anni trenta e i quaranta.” In Marino Marini. Passioni visive, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi, 12–39. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

Fergonzi, Flavio, ed. Marino Marini: Arcadian Nudes. New York: Center for Italian Modern Art, 2019. Exhibition catalogue.

Giovanola, Gian Luigi. “Artisti Italiani. Marino Marini.” La Fiera Letteraria, January 7, 1951.

Guzzetti, Francesco. “Espressionismi.” In Marino Marini. Passioni visive, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi, 152–71. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

Marini, Marino. “Le mie sculture.” Tempo 4, no. 29 (December 14, 1939): 19.

Ojetti, Ugo. “La XX Biennale Veneziana. Scultori nostri.” Corriere della Sera, May 12, 1934.

Pazzaglia, Chiara. “Marino monumentale. I cinque rilievi per l’Arengario di Milano.” Studi di scultura 1, no. 1 (2019): 138–57.

Russo, Gianmarco. “I nudi femminili e le Pomone.” In Marino Marini. Passioni visive, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi, 122–37. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

Russo, Gianmarco. “Ragghianti critico di Manzù.” In Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti e l’arte in Italia tra le due guerre. Nuove ricerche intorno e a partire dalla mostra del 1967 “Arte Moderna in Italia 1915–1935”, edited by Paolo Bolpagni and Mattia Patti, 185–95. Lucca: Edizioni Fondazione Ragghianti Studi sull’arte Lucca, 2020.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, ed. Giovanni Carandente (Milan: Skira, 1998), 172 (no. 243) and 226 (no. 321).

- See Gianmarco Russo, “I nudi femminili e le Pomone,” in Marino Marini. Passioni visive, ed. Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2017), 130–31. See also the article by Giorgio Motisi in this issue.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 74 (no. 101).

- Ibid., 190 (no. 273).

- Ibid., 211 (no. 301) and 228 (no. 324). The link between this Pomona and the aforementioned Piccola danzatrice is underlined by the Danzatrice of 1949, which is a second redaction of the statuette formerly exhibited at CIMA. See ibid., 225 (no. 320).

- See the examples recorded by Chiara Fabi, “Cavalli e Cavalieri,” in Marino Marini. Passioni visive, 172–89.

- “The statue requires a […] vast research into forms, lines, masses. My women, whom some find clumsy, are an answer to this concern. In the figure, I commit myself to analyze, within the ever more unified, fixed and yet free and relaxed whole, the natural play of volumes. Nevertheless, this search for volumes is not the unique purpose of the sculptor, who must never forget that what touches most in a sculpture is always its poetry.” (“La statua impone […] una vasta ricerca di forme, di linee, di masse. Le mie donne, che alcuni trovano goffe, rispondono a questa preoccupazione. Nella figura, io mi propongo di approfondire, nell’insieme più unito, più fermo, e pure libero e sciolto, il giuoco naturale dei volumi.”) Marino Marini, “Le mie sculture,” Tempo 4, no. 29 (December 14, 1939): 19. All translations by the author.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 186 (no. 267).

- Raffaele Carrieri, Marino Marini (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1948), figure 61.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 97 (no. 138), 100 (no. 141), 105 (no. 147), 116 (no. 166), and 106 (no. 149). The Venere is catalogued by Carandente as a 1938–40 Giovinetta.

- Ibid., 120 (no. 171). See Russo, “I nudi femminili e le Pomone,” 132.

- See Francesco Guzzetti, “Espressionismi,” in Marino Marini. Passioni visive, 152–71, and the essay in this issue by Chiara Pazzaglia.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 142–43 (no. 197–99) and 169 (no. 240).

- Ibid., 154–55 (no. 213–15). On Marino and the bas-relief, see Chiara Pazzaglia, “Marino monumentale. I cinque rilievi per l’Arengario di Milano,” Studi di scultura 1, no. 1 (2019): 138–57.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 139 (nos. 193–94) and 187 (no. 268).

- See Russo, “I nudi femminili e le Pomone,” 132–35.

- “Poète de surfaces.” Gianfranco Contini, Vingt Sculptures de Marino Marini présentées par Gianfranco Contini (Lugano: Quaderni della Collana di Lugano, 1944), iv.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 121 (no. 172).

- “Onda plastica.” Carrieri, Marino Marini, 20.

- “Tronchi di cono.” Gian Luigi Giovanola, “Artisti Italiani. Marino Marini,” La Fiera Letteraria, January 7, 1951.

- See Gianmarco Russo, “Ragghianti critico di Manzù,” in Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti e l’arte in Italia tra le due guerre. Nuove ricerche intorno e a partire dalla mostra del 1967 “Arte Moderna in Italia 1915–1935”, ed. Paolo Bolpagni and Mattia Patti (Lucca: Edizioni Fondazione Ragghianti Studi sull’arte Lucca, 2020), 195.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 166 (no. 235).

- Ibid., 174 (no. 246).

- Ibid., 116 (no. 166).

- Ibid. See also Flavio Fergonzi, “Prima della fama internazionale. Temi della ricerca scultorea di Marino Marini tra gli anni trenta e i quaranta,” in Marino Marini. Passioni visive, 31.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 105 (no. 147).

- Ibid., 58 (no. 78).

- XX Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Catalogo (Venice: Ferrari, 1936), 51.

- “Mammalucco equestre.” Ugo Ojetti, “La XX Biennale Veneziana. Scultori nostri,” Corriere della Sera, May 12, 1934.

- Carlo Carrà, “Scultori italiani e stranieri alla XX Biennale di Venezia,” L’Ambrosiano, August 1, 1936.

- Lamberto Vitali, Marino Marini (Milan: Hoepli, 1937), plate 23.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 33 (no. 31).

- Marino Marini, ed. Filippo de Pisis (Milan: Edizioni della Conchiglia, 1941), figures 37 and 60.

- “Dettaglio, gesso.” Ibid., figure 48.

- “Nudo – 1935 (particolare).” Carrieri, Marino Marini, plate 3.

- See Flavio Fergonzi, “Fotografare (e pubblicare) le sculture: un antefatto anni trenta-quaranta per Marino e Manzù,” in Manzù/Marino. Gil ultimi moderni, ed. Laura D’Angelo and Stefano Roffi (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana, 2014), 45–61, and the text by Fergonzi in this issue.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 100 (no. 141).

- Ibid., 63 (no. 84).

- See Russo, “I nudi femminili e le Pomone,” 122–38.

- See Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, 58–59 (no. 78), 62 (no. 83), and 63 (84b)

- Marino Marini: Arcadian Nudes, ed. Flavio Fergonzi (New York: Center for Italian Modern Art, 2019), 63.