Depero’s ‘Bolted Book’ and Futurist Publishing

Melania Gazzotti Melania Gazzotti Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://italianmodernart-new.kudos.nyc/journal/issues/depero/

This paper summarizes the main features of Futurist books, accounting for their complex originality. Futurists, from early in their movement, employed books as a privileged means of experimentation both in terms of graphics and contents. Authors like Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Francesco Cangiullo, Carlo Carrà, and Ardengo Soffici explored the visual, graphic, and onomatopoeic possibilities of written words in parolibere (words-in-freedom). These authors put into practice a typographic revolution, which aimed to subvert the usual order of language on a page, through the use of different characters and colors. The book Depero futurista, designed by Fortunato Depero and published by Fedele Azari in 1927, also known as ‘Bolted Book,’ can be considered an overview of these graphic innovations and a masterpiece in the history of printing.

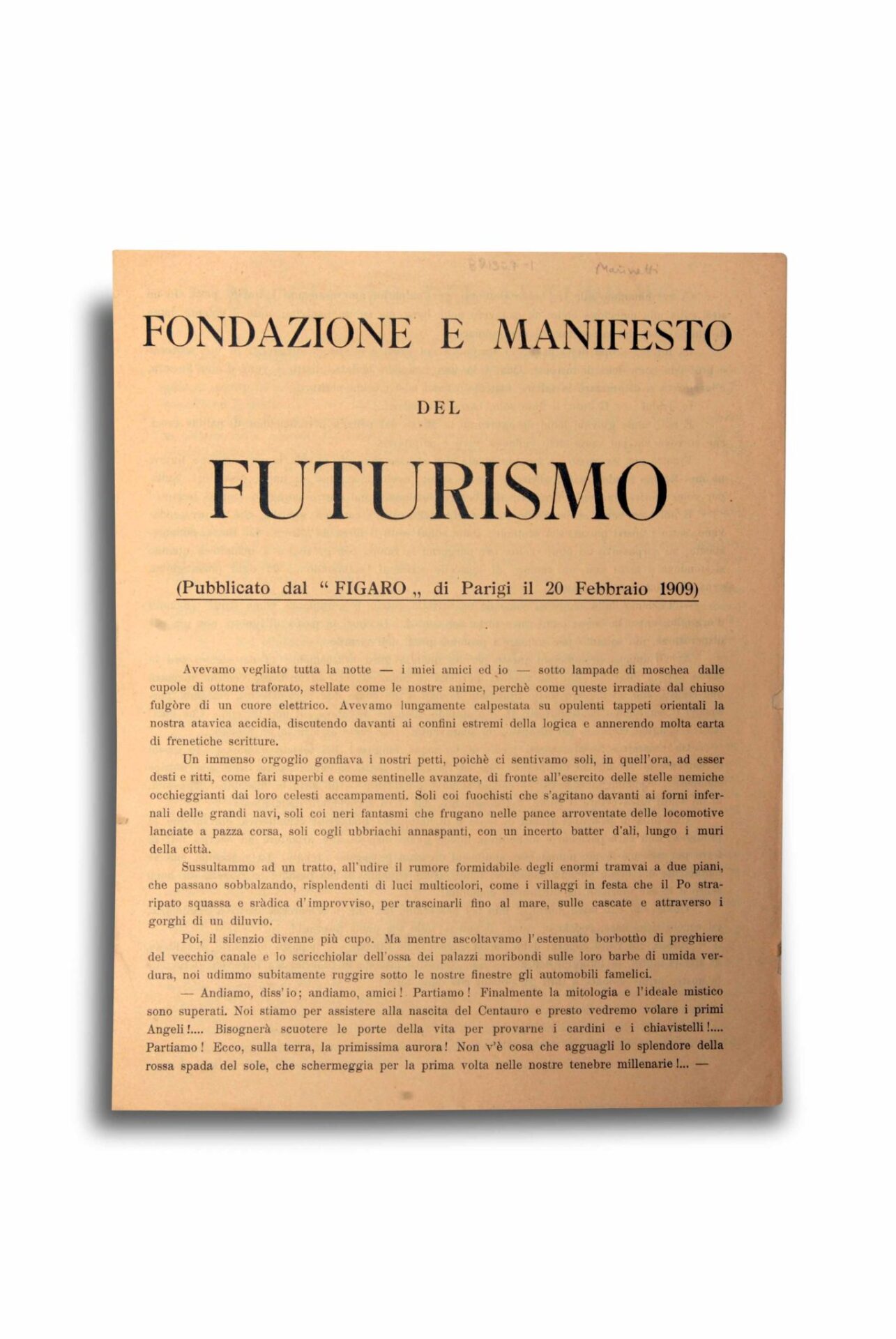

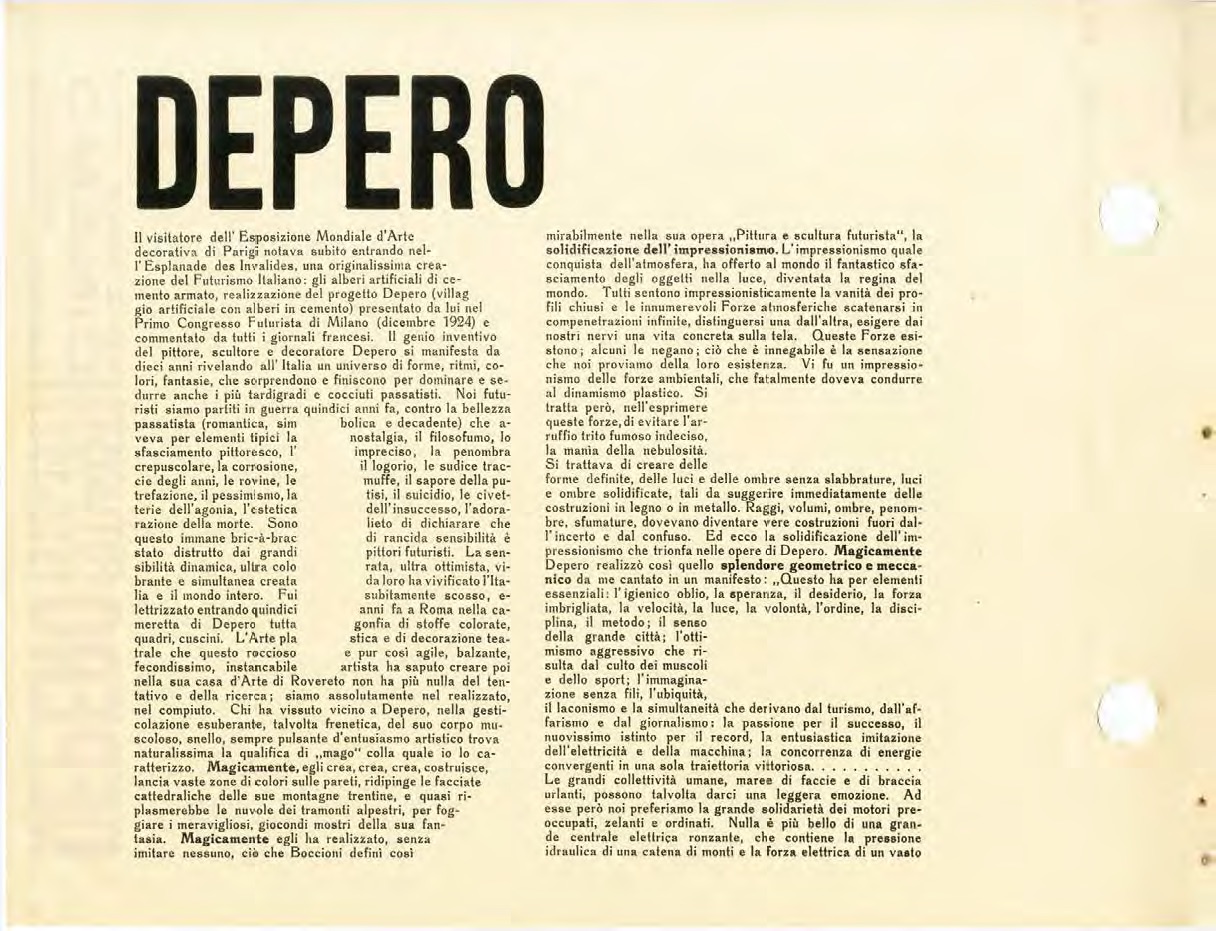

When the first Futurist manifesto was published in the French newspaper Le Figaro on February 20, 1909, no artist could properly define himself as a Futurist (figure 1). Written by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, this founding document outlined the vision of a movement that had not yet been created. With its emphatic prose, the text encouraged artists to break away from the cultural and literary traditions of the time. The true starting point of Futurism was, in this sense, based on a written declaration of intent, as opposed to artistic practice. In transmitting his Futurist ideas to the world, Marinetti continued to employ methods of verbal communication, rather than visual culture; he upheld writing as a powerful tool of persuasion, and printing as a most effective system of dissemination.

Over subsequent years, the Futurists followed Marinetti’s lead and also wrote hundreds of manifestos concerning art – including literature, painting, music, cinema, sculpture, architecture, photography, and theatre – as well as everyday life and customs. These texts were published in newspapers and magazines, or else formatted as leaflets that were printed in hundreds of copies, sent by mail to critics and intellectuals, distributed on the streets, and even dropped from airplanes over towns.1 With the exception of the founding manifesto (which was influenced by the Symbolist tradition), these Futurist treatises were concise, clear, direct, and showed a determinate intention to experiment in writing.

Throughout their many texts, the Futurists fostered innovative styles of writing and justified their choices with precise theoretical references. For example, in the Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista (Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature; 1912),2 which concerns poetic inspiration, Marinetti describes how to transcend free verse: he encourages writers to destroy the syntax, to abolish adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, and punctuation, to use verbs in the infinitive form and to connect nouns by analogy. Marinetti explains the ideal application of these rules through his poem La battaglia di Tripoli (The Battle of Tripoli; 1912), a collection of reports on his war experiences in Libya. Yet, this composition did not completely challenge traditional syntax. As with other texts produced at this initial phase, its innovation primarily lied in themes and content; this can be seen in Marinetti’s editorial work. Through his publishing house, Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia,” Marinetti edited free verse written by young and promising writers. Marinetti considered books to be the main medium of his propaganda. For this reason, he published between one and two thousand copies of each publication, an impressive number for the editorial market of the time. He would then distribute some copies freely by mail to critics, journalists, and intellectuals, with no regard for the economic benefits.

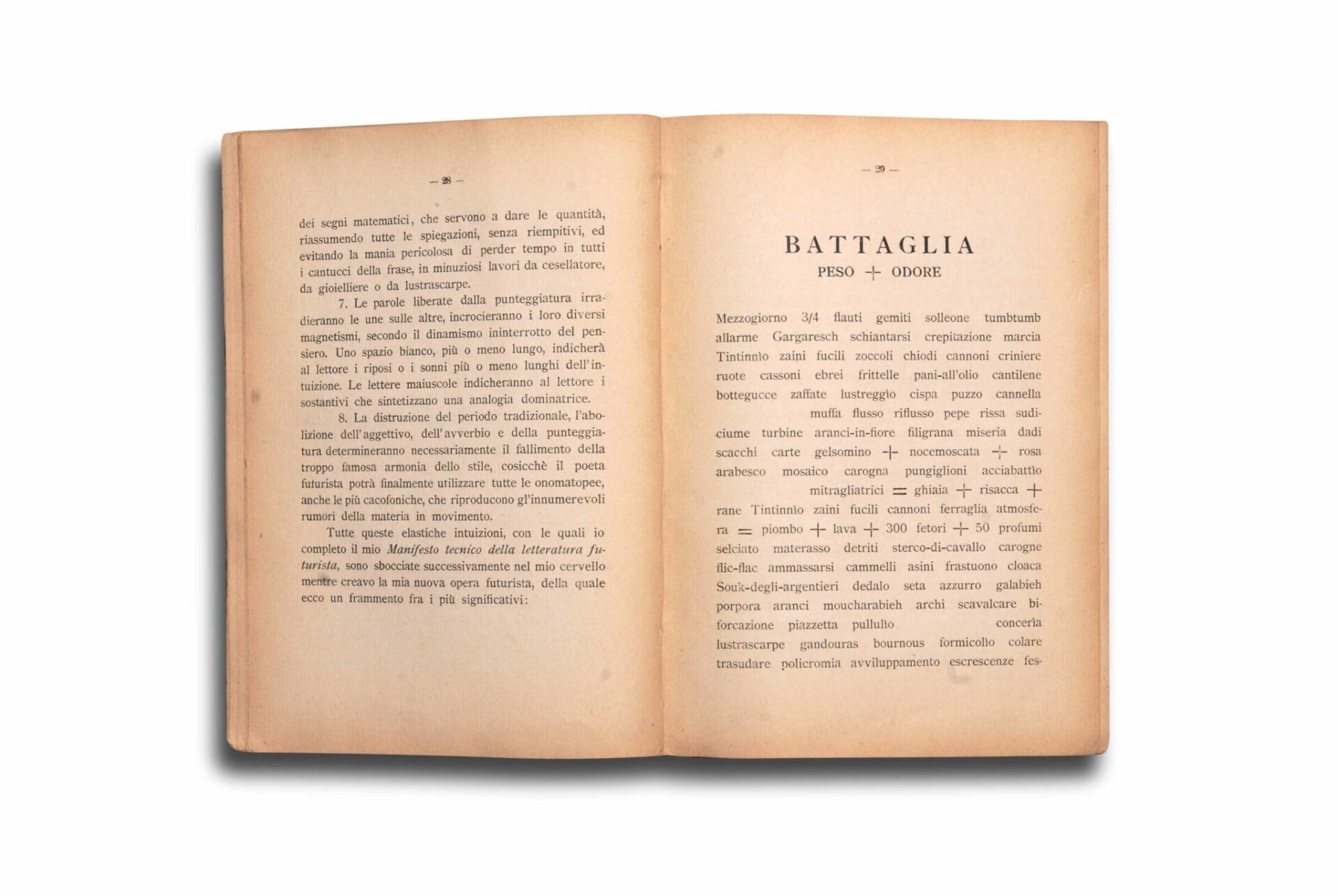

Even Marinetti’s first words-in-freedom composition, Battaglia peso + odore3 (Battle Weight + Smell; 1912; figure 2), did not introduce particularly bold typographic experimentations, though at points mathematical symbols were used in place of punctuation and conjunctions. Written by the poet while he was a war correspondent during the Libyan conflict, this text includes an accumulation of images evoked through a quick succession of nouns and verbs in the infinitive. It may very well be considered the link between the free verse and the subsequent parolibere (words-in-freedom).

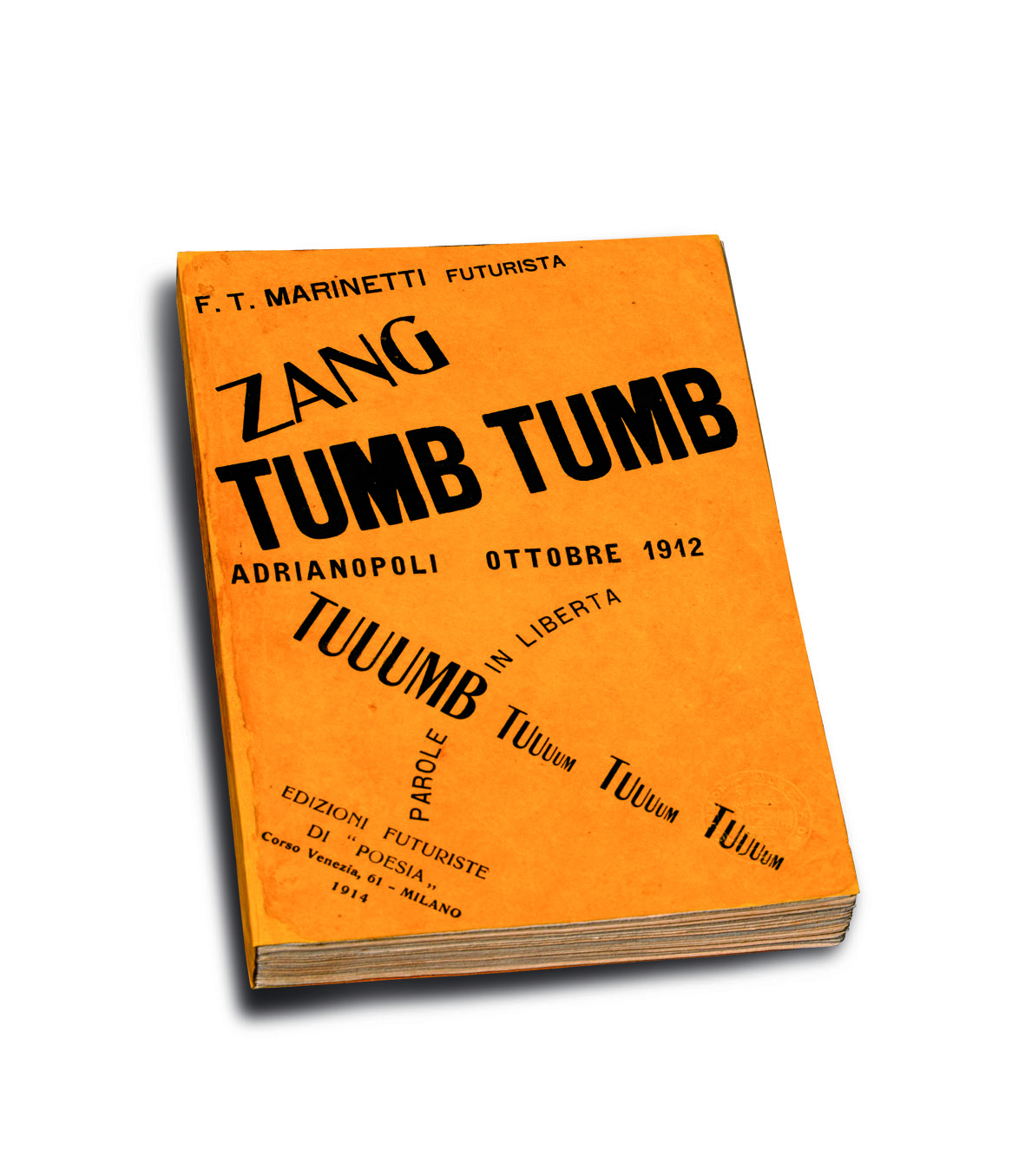

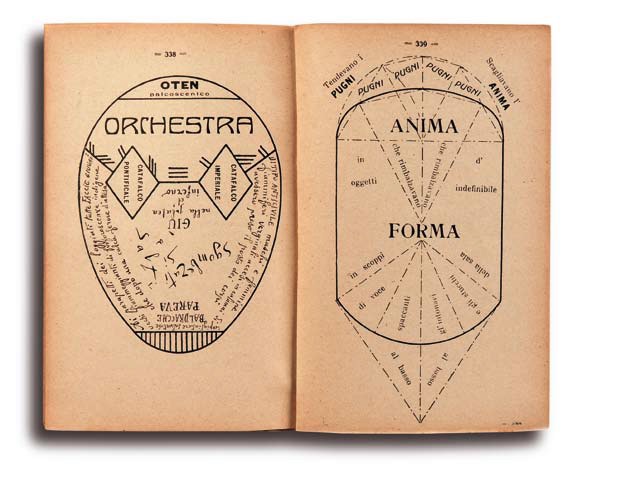

This volume collected various poems previously published in the Florentine magazine Lacerba that center on the besiege of the Turkish town Adrianople. Although Marinetti himself was present at this event, he employed in his own account with an impersonal writing style characterized by the disappearance of the narrator. Marinetti described a collective action, which took place all at once and therefore could not be contained in a rigid narrative structure, organized chronologically (figure 4).

Altogether, this text was designed to surprise the reader; the graphic, visual, and phonetic elements of its words were as important as their respective semantic connotations. Moreover, the linear progression of reading from left to right was disrupted, inviting the readers to instead look haphazardly throughout the page. Marinetti also created a subtle equilibrium between typographic characters and blanks, which transformed them into a structural elements of the composition and emphasized the materiality of words. Blanks were meant not only to evoke silence, but also to imbue the spatial and temporal aspects of the reader’s experience with pauses. The disposition of the text and choice of fonts was revolutionary for this epoch, especially from a technical point of view, if one considers the limited machinery and printing processes available at the time.

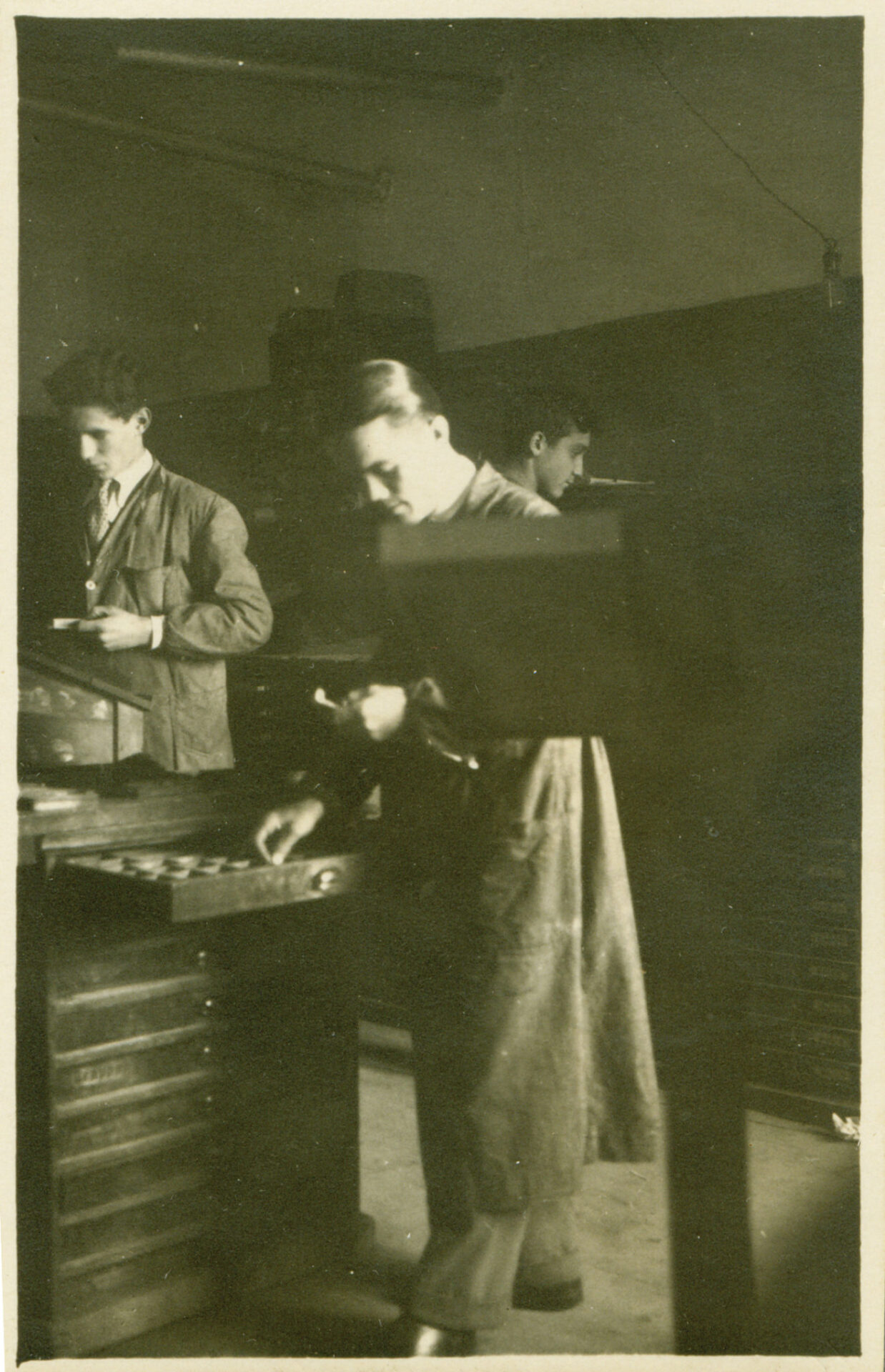

Two techniques were mainly used to compose these texts. In the more artisan method, wooden types were cut and then stacked together. In this case, the printer’s skill was very important, for he had to select the characters that would be included in the poet’s sketches and find technical solutions suitable to achieve the desired outcome. The other, more conventional technique consisted of reproducing the text through photo-engraving, a process in which images were duplicated by transferring graphic material photographically to a plate or another surface that would then be etched for printing.4 Employing this technique, poets could produce collages of characters and graphic elements that were photo-mechanically reproduced by the printer. The results of these two techniques were different. The moveable type press often robbed compositions of their dynamic visual effect; the device enabled individual words to give a powerful impression and endowed artists with ample, yet defined composite solutions. Photoengraving, meanwhile, allowed greater creative freedom. However, the words-in-freedom produced through this technique typically turned out to be photographic reproductions of original works of art.5

As stated at the end of Zang Tumb Tuuum, the realization of the first words-in-freedom book was made possible by the ability and creativity of the printer Cesare Cavanna, a loyal collaborator of the Futurists who worked in Milan for the printing press Angelo Taveggia. A poet as well as an anarchist, Cavanna produced the most famous words-in-freedom books published by Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia” by using inventive typographic strategies, and Marinetti was deeply involved through all the stages of the production.6

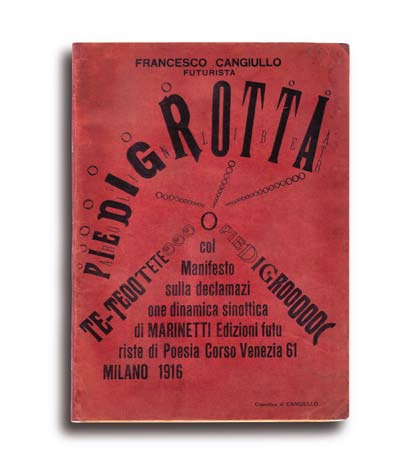

Many Futurist poets followed Marinetti’s principles and instructions. One such author was Luciano Folgore whose Ponti sull’oceano7 (Bridges on the Ocean) was published in the the same year as Zang Tumb Tuuum by the Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia,” a house known for printing the most remarkable publications of this kind, such as Paolo Buzzi’s L’ellisse e la spirale. Film + Parole in libertà (Ellipse and Spiral. Film + Words-in-Freedom; 1915; figure 5), Corrado Govoni’s Rarefazioni (Rarefactions; 1915; figure 6), Auro D’Alba’s Baionette (Bayonets; 1915), and Francesco Cangiullo’s Piedigrotta (1916; figure 7).

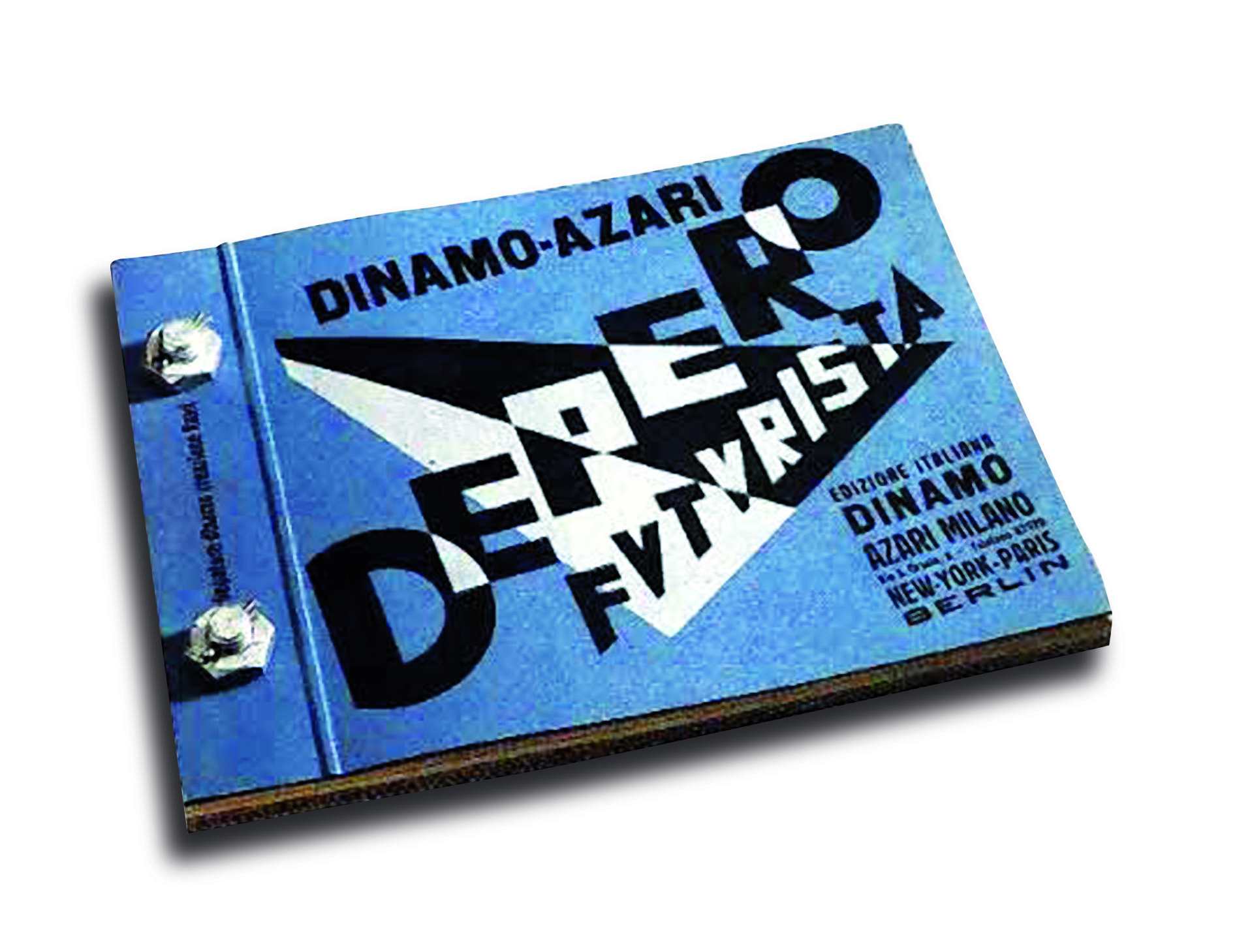

The book Depero futurista, designed by Fortunato Depero and published by Fedele Azari in 1927 can be considered a comprehensive composite of all the Futurist graphic innovations. The volume, printed in an album format, is also known as libro imbullonato (‘Bolted Book;’ figure 8), because the cover boards were held together by two metal bolts. Azari, who was also an aviator, initially proposed the idea for the bolts, and they were originally designed to be in wood8 for the hardback edition and in metal for the luxury edition. However, ultimately, they were all produced in metal for economic reasons. Incidentally, the use of metal was completely in step with the focus on the machine that characterized Futurism in the early 1920s. The presence of bolts likened the book to a mechanical object that, as such, could be disassembled and reassembled to modify the order of its unnumbered pages or even add additional pages.9 Considering these associations, it is no surprise that Depero described his book in the introduction of the text as a product of the Machine age.10

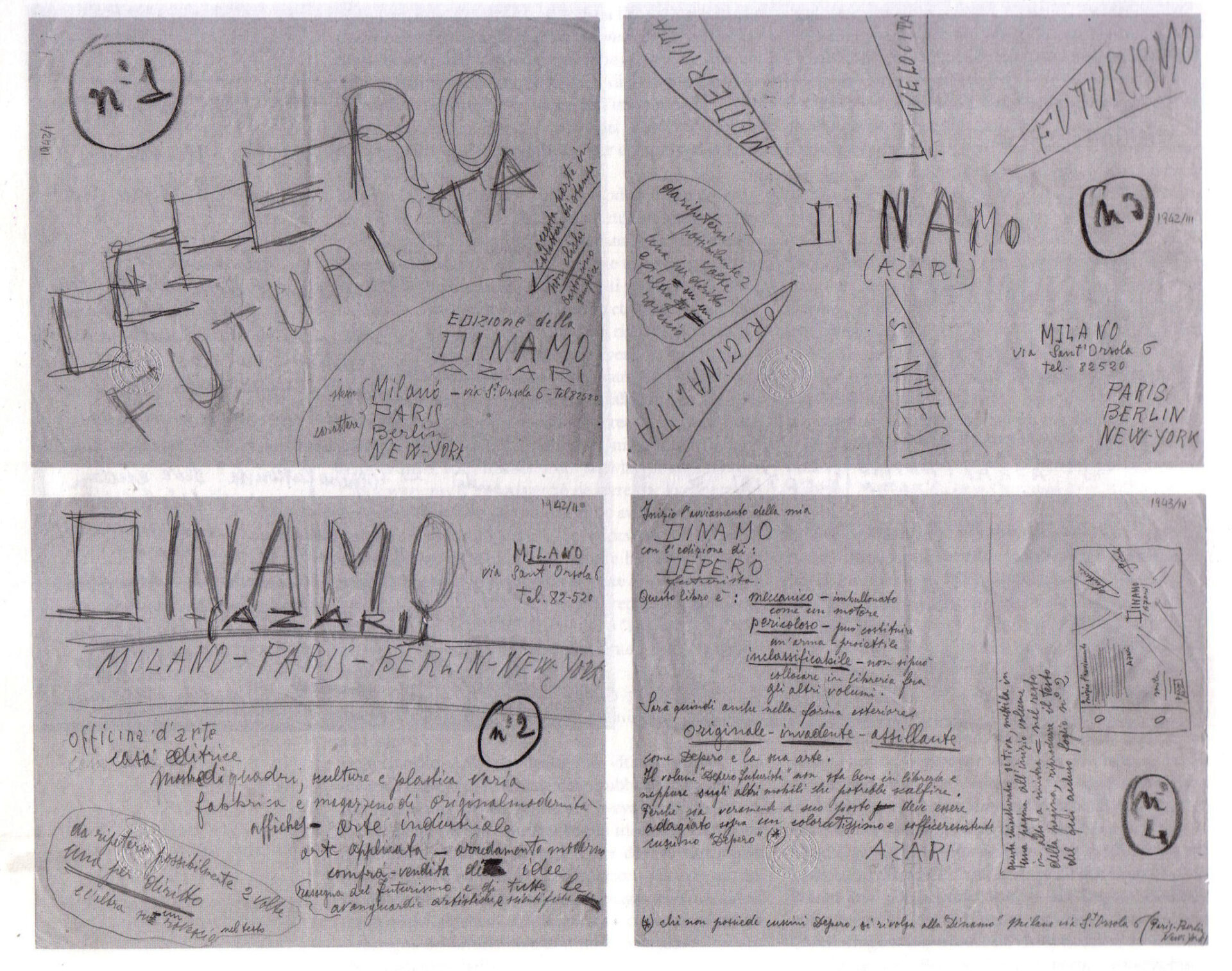

The ‘Bolted Book’ was published by the Milanese publishing house, Dinamo Azari (figure 9). Although the text was initially intended to be printed in 2000 copies,11 the publisher later realized this plan would be too expensive; the run was thus cut to 1000 copies. The editions contained at least three different covers. Produced for celebrities such as Mussolini and Marinetti, the luxury edition, for instance, had a metal cover.12 This construction anticipated Marinetti’s later Parole in libertà futuriste tattili termiche olfattive (Words in Futurist, Olfactory, Tactile, Thermal Freedom), a book with metal pages and binding, published in 1932 and printed by a lithographic process.

A strong proponent of advertising and self-promotion (or auto-réclame, as he called it),13 Depero conceived his book to spread and promote Futuristic aesthetics and, particularly, his own work as a painter, as well as a graphic and set designer. The volume was also designed to advertise the artist’s own Casa d’Arte (The House of Art) based in his hometown Rovereto, Azari’s Casa d’Arte, and his publishing house in Milan (figures 10–11).

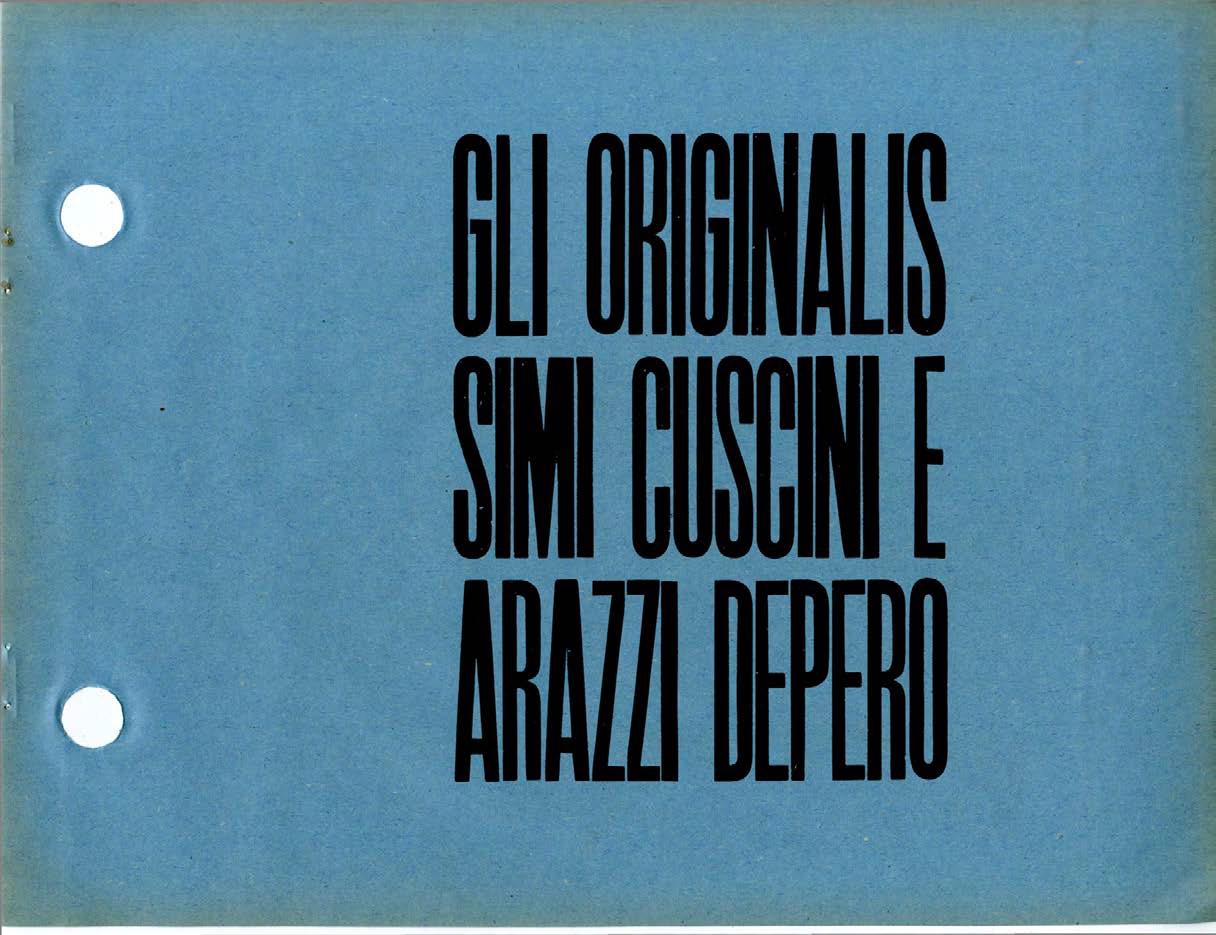

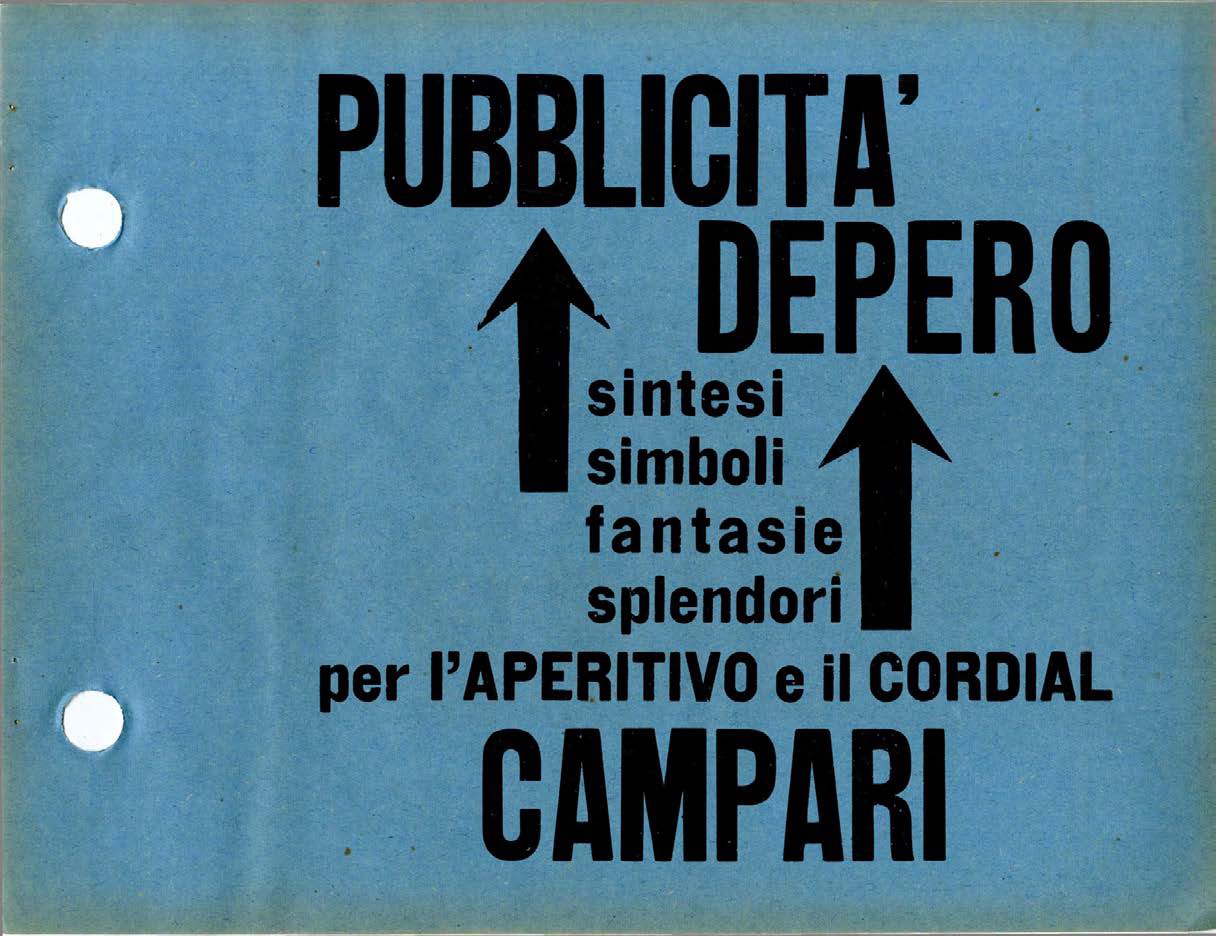

Depero understood the importance of an artist promoting his own work and how a book could serve as an effective tool for the dissemination of that work. In this sense, he was clearly influenced by Marinetti and his idea of spreading the Futurist theories through printed manifestos, books, and magazines. The ‘Bolted Book’ was an overview of Depero’s work from 1913 to 1927, including his theatrical projects (such as Il canto dell’usignolo [The Song of the Nightingale] and Balli plastici [Plastic Ballets]), drawings, and photographs of his set designs and costumes. It also encompassed images of objects produced in the Casa d’Arte Depero, the studio-workshop where, along with his wife Rosetta, he produced a vast quantity of toys, decorative objects, tapestries, and fabric. A chapter of the book was even devoted to Depero’s first Campari advertising campaign. Depero worked for Davide Campari for more than ten years, starting in 1925 (figure 12). Under Campari, he designed posters and advertising gadgets, such as lamps, trays, puppets, and the famous Campari soda bottle (1932), which is still in production today.

The text of Depero’s book introduced many typographic innovations; each page combined different fonts, colored paper of varying thicknesses, and colored inks (figures 13–14). In these typographic compositions, Depero refused symmetry and perpendicularity in favor of dynamism. He formed text into different shapes, so that words took on an autonomous and iconic status, and the writing was transformed into a figure. Depero was influenced by German and Russian typographical innovations, but above all by words-in-freedom poems. He created the expression ‘onomalingua’ (onomatopoetic language) in order to describe a personal onomatopoetic and non-semantic interpretation of words-in-freedom.

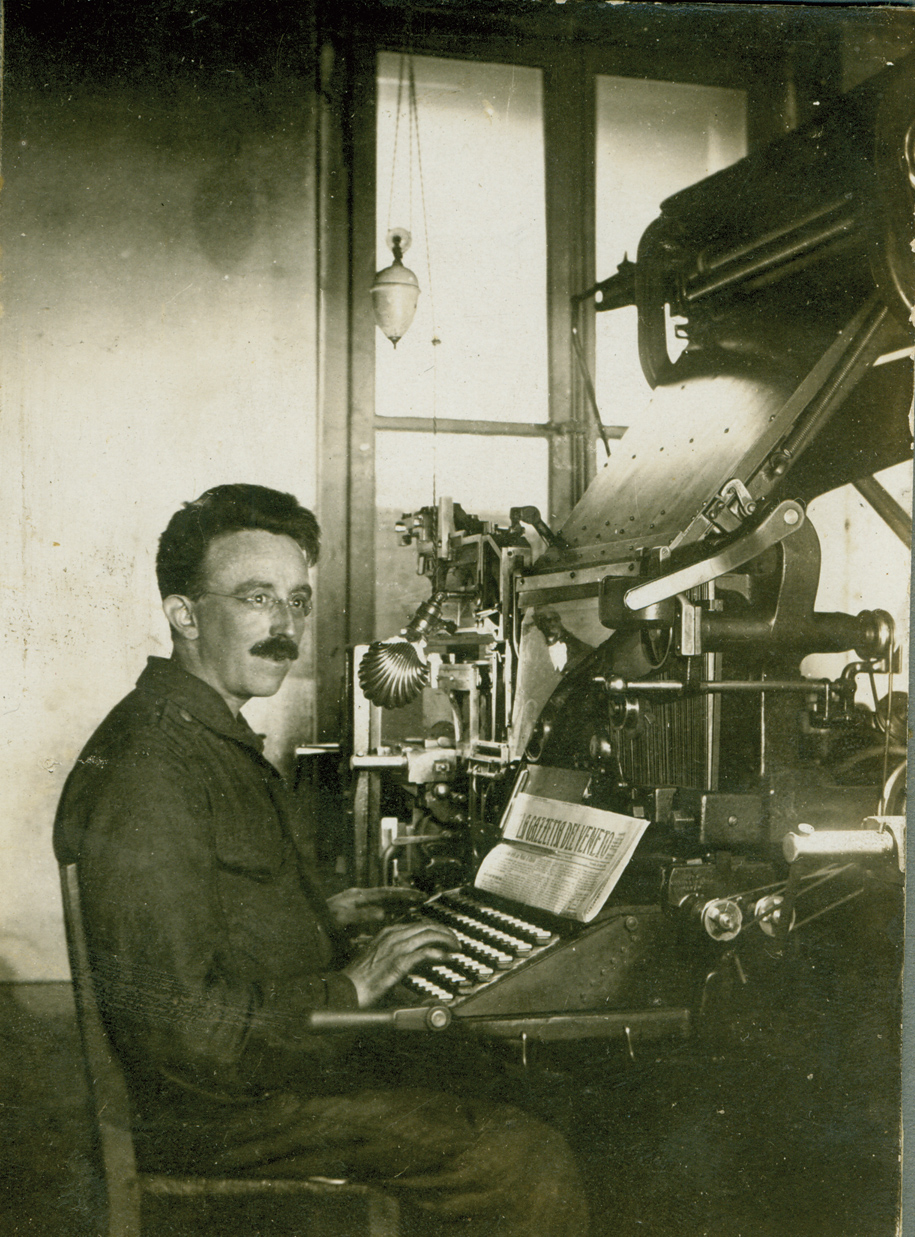

Depero futurista was printed in a small and artisanal print shop in Rovereto called Mercurio, which is still operating today (figures 15–17). Like Marinetti, Depero was familiar with the different techniques of printing and the distinct possibilities they offered. For this reason, he was deeply involved in the production of his book and was especially concerned with the typesetting and printing.

Being physically present during this process allowed him to direct and supervise every single detail. Throughout production, he kept in constant contact with the publisher Azari14 in order to obtain his approval regarding the graphic composition of each page (figure 18). Their correspondence suggests that Azari proposed the idea of the bolts, as well as the cover design and the title of the book.15 It also reveals that the book’s extraordinary range of graphic solutions were conceived by Depero. The result of this collaboration is a masterpiece in the history of printing where each page is a manifesto of innovative graphic design as well as an instrument with great promotional and propagandistic impact.

The immense influence of the ‘Bolted Book’ on the epoch’s graphic design scene is demonstrated by two occurrences. In 1928, the Dada artist Kurt Schwitters saw the volume and wrote a letter to Depero asking to meet him and to congratulate him on “his magnifique book.”16 When Schwitters got a copy of the ‘Bolted Book’ for his personal library, he enthusiastically showed it to all of his visitors. Later in 1933, Jan Tschichold, the author of the seminal book Die Neue Typographie, also wrote a postcard to Depero acknowledging the significance of this work in the development of German and Swiss typography over the previous five years.17

Another fact makes the story of the ‘Bolted Book’ unique in the Futurist publications panorama. The production of the book mirrored the aspiration that Futurist art could be spread to the most advanced and modern art market of the world: the American market. In fact, Azari intended to open a publishing house and a branch of his Casa d’Arte in New York as was announced in the cover of Depero futurista. Azari’s project was scheduled for 1927, the year the ‘Bolted Book’ was published. As evidenced by the letters between Azari and Depero, he saw the book as his calling card for America.18 Unfortunately Azari was only able to stay in New York for a month before returning to Italy because of bureaucratic complications.19 Whereas after the release of Depero Futurista, Depero moved to New York in 1929 (figure 19), becoming the first – and only – Italian Futurist to live in the United States. In his adventure across the ocean, Depero took various copies of the ‘Bolted Book’ to donate to celebrities, clients, and institutions. He had also the occasion to exhibit his publication and all its graphic innovations to the American audience in 1929 during the Mostra del libro italiano (Exhibition of the Italian Book at Arnold-Consable & Co, New York, March 15–30, 1929).20

Bibliography

Antolini, Roberto, ed. Libri taglienti esplosivi e luminosi: Avanguardie artistiche e libro tra Futurismo e libro d’artista. Rovereto: Nicolodi, 2004.

Belli, Gabriella. “La scrittura futurista e l’uso del manifesto.” In La parola nell’arte: Ricerche d’avanguardia nel ‘900: dal Futurismo a oggi attraverso le collezioni del Mart, 45–49. Milan: Skira, 2007.

Caruso, Luciano, ed. Il libromacchina (imbullonato) di Fortunato Depero. Florence: S.P.E.S., 1987.

D’Alessandri, Antonella. “La genesi del libro imbullonato dalle lettere di Fedele Azari e Fortunato Depero.” In Libri taglienti esplosivi e luminosi. Avanguardie artistiche e libro tra Futurismo e libro d’artista, edited by Roberto Antolini, 115–128. Rovereto, Nicolodi, 2004.

Depero, Fortunato. Depero Futurista. Milan: Dinamo Azari, 1927.

Hollis, Richard. Graphic Design: A Concise History. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994.

Rothschild, Deborah, Darra Goldstein, and Ellen Lupton, eds. Diseño gráfico en la era mecánica: La colección Merrill C. Berman. Valencia: IVAM, 1999.

Salaris, Claudia. “Dalle Dolomiti ai grattacieli.” In Fortunato Depero: Un futurista a New York, edited by Claudia Salaris, 215–223. Montepulciano: Del Grifo, 1990.

Salaris, Claudia. Marinetti: Arte e vita futurista. Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1997.

Tonini, Bruno. “Avant-Garde Typography (1900–1945): Theories and Typefaces.” In La vanguardia aplicada: tipografía y diseño gráfico (1890–1950), 397–419. Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 2012.

How to cite

Melania Gazzotti, “Depero’s ‘Bolted Book’ and Futurist Publishing,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/deperos-bolted-book-and-futurist-publishing/, accessed [insert date].

- Gabriella Belli, “La scrittura futurista e l’uso del manifesto,” in La parola nell’arte: Ricerche d’avanguardia nel ‘900: dal Futurismo a oggi attraverso le collezioni del Mart (Milan: Skira, 2007), 46.

- The manifesto Supplemento al Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista (Supplement to the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature) was also published as a leaflet in Italian and French in 1912.

- Battaglia peso + odore (Battle Weight + Smell) was included in the Supplemento al Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista (Supplement to the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature).

- Richard Hollis, Graphic Design. A Concise History (London: Thames & Hudson, 1994), 39.

- Deborah Rothschild, Darra Goldstein and Ellen Lupton, eds., Diseño gráfico en la era mecánica: La Colección Merrill C. Berman (Valencia: IVAM, 1999), 68.

- Claudia Salaris, Marinetti: Arte e vita futurista (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1997), 73.

- The cover of Ponti sull’oceano was designed by the architect Antonio Sant’Elia.

- Azari’s letter to Depero is dated March 13, 1927 and preserved at MART – Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (from now MART). Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero.

- Bruno Tonini, “Avant-Garde Typography (1900–1945): Theories and Typefaces,” in La vanguardia aplicada: tipografía y diseño gráfico (1890–1950) (Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 2012), 404.

- In Depero futurista, Depero described the volume as “mechanical, bolted together like an engine – dangerous, capable of serving as a weapon. It cannot be placed on the shelves amongst other books.”

- Azari’s letter to Depero (February 16, 1927; MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero).

- We know from a letter by Azari to Depero (July 27, 1927; MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero) that 10 copies of the luxury edition were planned: one for Mussolini, one for Marinetti, one for Depero, one for Azari plus six other copies. One of these six copies was bought by Castello di Trento and it is still preserved in the institution’s library.

- Depero described in Depero futurista the auto-réclame as “not a vain, useless and exaggerated expression of megalomania, but rather an essential NECESSITY to let the public quickly get to know ideas and creations.”

- Azari’s letters to Depero are preserved at MART. Archivio del’900. Fondo Depero. Part of their correspondence is published in Roberto Antolini, ed., Libri taglienti esplosivi e luminosi: Avanguardie artistiche e libro tra Futurismo e libro d’artista (Rovereto: Nicolodi, 2004). A few letters are also published in Luciano Caruso, ed., Il libromacchina (imbullonato) di Fortunato Depero (Florence: S.P.E.S., 1987).

- Azari’s letter to Depero (July 11, 1927; MART. Archivio del’900. Fondo Depero).

- The letter, dated to April 6, 1928, and sent from Porto Empedocle, is also signed also by Rudolf Dustmann. This document is preserved in the Fondo Depero at MART.

- Tonini, La vanguardia aplicada, 404.

- Azari’s letter to Depero (August 3, 1927; MART. Archivio del’900. Fondo Depero).

- Antonella d’Alessandri, “La genesi del libro imbullonato dalle lettere di Fedele Azari a Fortunato Depero,” in Libri taglienti esplosivi e luminosi, 118.

- Claudia Salaris, “Dalle Dolomiti ai grattacieli,” in Fortunato Depero. Un futurista a New York, ed. Claudia Salaris (Montepulciano: Del Grifo, 1990), 219.