Introduction

An overview of the fifth issue of Italian Modern Art, dedicated to Italian sculptor Marino Marini (1901-1980).

Photographing Sculpture: A Comparison between Marino Marini and Giacomo Manzù from 1930 to 1950

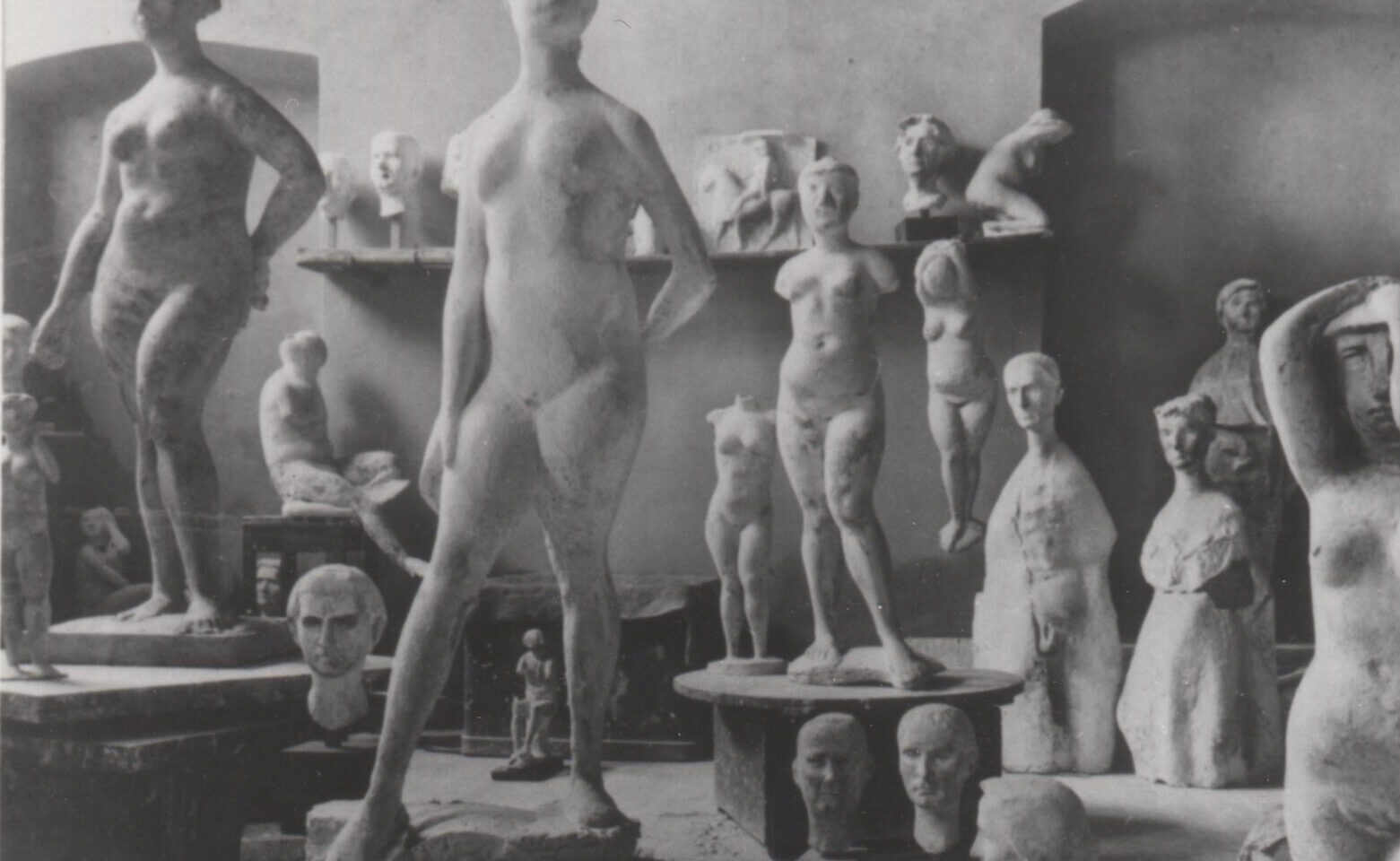

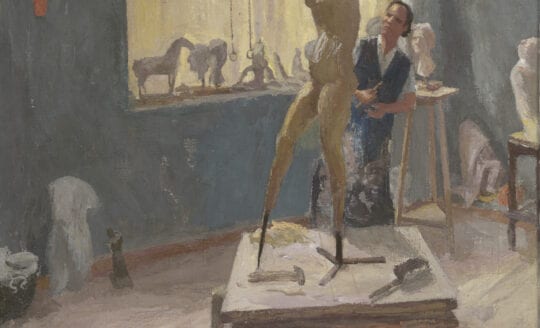

This essay examines the crucial role that photography played in the affirmation and critical interpretation of Marino Marini (1901-1980) and Giacomo Manzù (1908-1991), two of Italy’s foremost modernist sculptors. Through a close comparison of photographs published in books, art journals, and magazines, the author demonstrates how the choices that photographers make when portraying sculpture greatly influence the legibility of a work. The importance of photographic reproduction became particularly evident in Italy during the 1940s: given the constraints that World War II imposed on the travel of artworks and the organization of art exhibitions, the circulation of photographs was a pivotal instrument in establishing the reception of Marini’s and Manzù’s sculptures, with significant reverberations in the postwar era. The photographers’ choices in terms of angle, cropping, backgrounds, and lighting thus provided a first, critical reading that is here thoroughly studied over the course of three decades.

Reclaiming a Past: Marino Marini and the (Non-)Classical Tradition

Strongly rooted in the cultural and visual tradition of his home country, Marino Marini’s artistic production is the result of an uninterrupted dialogue with the art of the past, spanning from archaic Greece to Renaissance Italy, from imperial Rome to nineteenth-century European sculpture. In the vast repository of models that Marini drew upon, ancient art holds a significant place; rather than focusing, however, on the Greek and Roman artworks that fuelled artistic imaginations for centuries, from the 1920s Marini showed an interest in ancient civilizations outside of the established canon of classical antiquity, most notably those of ancient Etruria and Egypt. This appropriation is usually understood in connection with the widespread coeval fascination for archaic and pre-classical forms and as part of the Etruscan revival so proudly pursued by artists such as Arturo Martini and Massimo Campigli. Yet, little attention has been given to the momentous time at which Marini’s interest in such artifacts developed – a time of archaeological discoveries, flourishing scholarly literature, and the rearrangement of key museum collections that Marini had direct access to. By placing Marini’s interest, above all, in Etruscan artworks within the framework of the early twentieth-century cultural interest surrounding that civilization, this paper contributes to a richer understanding of Marini’s sculpture, locating his work more accurately on the map of the reception of antiquity in modern Italian art.

In the Sign of Tuscan Artistic Tradition: The Creative Experience of Marino Marini at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, 1917–1923

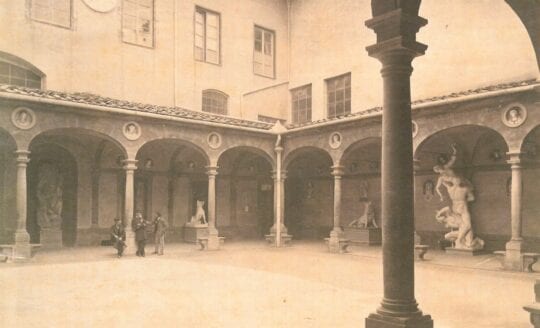

This article investigates Marino Marini’s training at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze on the basis of unpublished documents, preserved in the historical archives of that institution. What emerges from those documents is that Marini was initially enrolled in 1917 in the so-called Scuola di Ornato, under the guidance of Augusto Burchi and, in particular, Galileo Chini. Subsequently, from January to October 1922, Marini attended the Scuola di Incisione with Celestino Celestini, whose results were a series of engravings partly analyzed by Mario De Micheli and Giorgio Guastalla in 1990. Finally, from the fall of 1922 to the summer of the next year, Marini took part in the sculpture lessons held at the Accademia by Domenico Trentacoste, one of the most famous Italian sculptors of the time. Although scholars have always given little importance to Marini’s training at the Accademia of Florence, the legacy of that course has left a trace in the work of the great sculptor through different perspectives. On the one hand, the Accademia initiated him into the practice of engraving and sculpting. On the other, the training with professors such as Galileo Chini convinced Marini to look with interest at the models of Tuscan Renaissance art even in the late 1920s, after the end of a long training phase that lasted a total of six years.

Masks and Faces: Marino Marini’s Dialogue with Antiquity in Female Nudes and Portraits

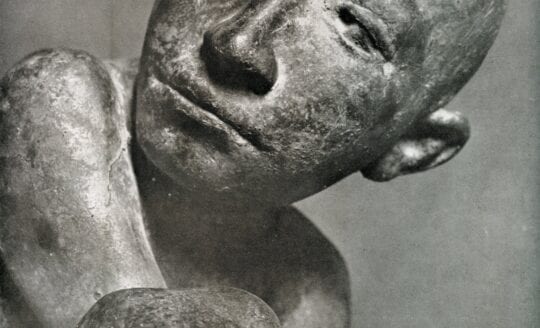

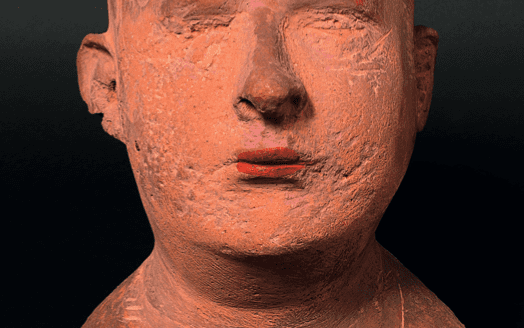

In a long-ignored text, the painter Gabriele Mucchi recalls Marino’s relationship with a fine arts student named Sistina. According to Mucchi, this girl “posed for some versions of the Pomona” and “stayed with Marino until he abandoned her for a girl who oddly resembled her: Mercedes.” This sentence helps to better understand the so-called “portrait” Sistina (c. 1938). This terracotta head, though, seems to have nothing to do with Marini’s several portraits of Mercedes. Instead, it is similar to the faces of some of his female nudes of the late 1930s. Considering both these observations and Mucchi’s testimony, the work cannot be defined as a “portrait” in the strict sense of the word. It is, more likely, a part of a full-length figure, from which it was detached at an unknown date. In other words, Sistina is the model, but she is not portrayed. The Sistina episode leads us to reconsider some differences in the artist’s work on female nudes, on the one hand, and portraits, on the other. Starting from this reflection, the second part of the paper is devoted to Marini’s dialogue with antiquity in the two genres taken into account. Firstly, the text focuses on the sculptor’s attention to some ancient models. In his full-length figures, for example, Marini mainly refers to the seductive bodies and the static faces of Greek art. In particular, the latter seem to be employed as inexpressive “masks” useful for bringing out, by contrast, the vital sensuality of the female nudes. Contrariwise, his portraits seem rather linked to Etruscan, Roman, Egyptian, and Renaissance models, conceived as examples of strong individual characterization. Secondly, the article aims to analyze the surface treatment in the two distinct genres. On the one hand, the scratches on the female nudes provide a new intense humanity and pictorial allure to the plastic construction of volumes. On the other, scraping interventions on the portraits were employed especially to avoid excessive realism and to accomplish an elegant archaeological effect. In both cases, Marino was like an imaginative archaeologist. Through opposite ways, he created his fascinating characters, ancient yet modern.

A Path à rebours for Marino Marini’s Wooden Nudo femminile of 1936–41

In 1939, in one of his best-known statements, Marino Marini juxtaposed life-size female nudes with portraiture. Compared to portraiture, the sculptor wrote, “the statue requires a vaster research into forms, lines, masses. My women, whom some find clumsy, are an answer to this concern. Nevertheless, this search for volumes is not the unique purpose of the sculptor, who must never forget that what touches most in a sculpture is always its poetry.” This paper elaborates on Marini’s female nudes of the late thirties and forties in light of the relationship between form and poetry, or in other words, between the plastic construction of volumes and the expressive power of surfaces. Firstly, it discusses the fracture between form and modeling, volumes and profiles, plastic development and surface definition, tracing a path à rebours from the Danzatrice (Dancer) of 1949 now at MoMA in New York to the Maschera (Mask) of 1936 at the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia. Secondly, it offers an examination of Marino’s wooden Nudo femminile (Female nude) traditionally dated to 1932, showing a mechanical dependency between the latter and the 1936 statue, and fixing the chronology between 1936 and 1941.

From Pomona to the Three Graces: Reshaping Female Nudity in Marino Marini’s Reliefs

In the early-1930s Italy, monumental sculptors were commissioned to create reliefs to be situated within architecture. In the eyes of Marcello Piacentini, the leading voice of the stile littorio (“lictor style”), the constraints inherent to the relief as a sculptural form would lead to an ideal synergy between artists and architects. Already acclaimed for his free-standing sculptures, Marino Marini first presented reliefs at two major exhibitions curated by Mario Sironi: in 1932, at the Mostra della rivoluzione fascista; and in 1933, for the Milan Triennale. For an artist inclined to sculpt in the round, thinking “in relief” involved different problems. This essay aims to investigate Marini’s complex study of the fixed point of view of the relief in the works dominated by the presence of female figures. In 1939, he admitted that his main concern in the full-length figure was to analyze “the natural play of volumes” in space. Thus, transferring that figure to a surface forced him to rethink its sculptural significance. This essay specifically considers Marini’s public commissions in the 1930s, including his attempts to combine the free-standing Pomona with a fixed point of view, as well as his expressionistic turn in the 1940s, starting with his variations on the theme of the Three Graces. The traditional representation of the latter myth, at the core of the sculptor’s interests in the war years, helped Marini to investigate the relation of figures to their background. However, in his reliefs the myth was distorted in its dramatic application to modern-day content, probably looking at the contemporary work of Mario Mafai and Giacomo Manzù. In summary, this group of works helps to define the versatility with which Marini approached the sculptural theme of the female nude in relief.

“A Nordic Mystery”: Insights into Marino Marini’s Sojourn in Switzerland During World War II

This essay focuses on Marino Marini’s self-imposed retreat to Switzerland, his wife’s native country, in December 1942, to escape the bombings in Milan during World War II. He would return to Milan in the winter of 1945, resuming his professorship at the Brera Accademia di Belle Arti. His Swiss years were particularly fruitful and experimental, but also the darkest and least explored of his career. They influenced his most peculiar artworks (including the Archangels, Miracles, and Pomonas), marked by disproportionate shapes and corroded surfaces, and strongly inspired by the “Nordic mystery” towards which he felt instinctively attracted. Against the backdrop of the dramatic war years, this essay reassesses Marini’s work in the light of a broader emerging Swiss art scene of international artists, museum directors, art collectors, and critics who variously contributed to the widespread knowledge of his oeuvre.

When Parallel Lives Overlapped: Alexander Calder and Marino Marini

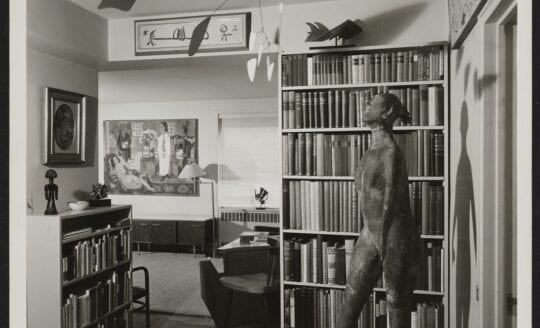

Alexander Calder and Marino Marini first encountered one another in 1950, during the Italian sculptor’s first visit to America. After this initial meeting, the two artists would continue to exchange correspondence for several years, especially during Calder’s participation in the 1952 Venice Biennale. Their social interactions developed out of their mutual friendship with and shared representation by the dealer Curt Valentin. As a result, both artists’ works were collected by the same patrons and displayed in spaces alongside one another, for example in Peggy Guggenheim’s Venice collection and that of Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., the owner of Fallingwater. Although art historical narratives have frequently focused on Marini as a sculptor looking backward, fascinated by the antique, and on Calder as an avant-garde innovator, breaking with traditional definitions of form, the similarities between the two artists—in their subjects and innovative techniques—demonstrate how both were men reflecting on their contemporary era. This article reflects upon surviving archival evidence from both the Calder Foundation and the Fondazione Marino Marini in Pistoia that illustrates their friendship.

Some Reflections on Marino Marini’s Legacy Through the Eyes of His Pupil, Alik Cavaliere

This article assesses Marino Marini’s legacy through the eyes of his disciple and successor as Chair of Sculpture at the Accademia di Brera in Milan, Alik Cavaliere. My investigation concentrates on Cavaliere’s (mostly) unpublished journals, in which the artist reported his thoughts on his relationship with his teacher and most of their private conversations from the 1960s to the 1980s. Based on this information, my essay investigates the impact that Marini had on his pupil within the context of their artistic and personal relationship. The analysis focuses on Cavaliere’s reworking of Marini’s concept of ‘the feminine’, which the journals demonstrate stemmed from an exchange of opinions between the two artists. Exploring Marini’s ambivalent idea of the ‘feminine’, oscillating between ‘traditional kindness’ and ‘cerebral sharpness’, I analyze how this concept affected his poetry and syntax. I argue that the dichotomous character of Marini’s female nudes, seen by critics as struggling between plastic volumes and erotic surfaces, might be traced back to the artist’s ambivalent idea of the ‘feminine’ itself; I then explore how the concept was assimilated and re-semanticized by Cavaliere in his work. In the second section of my paper, I apply this perspective to the analysis of two works, namely Marini’s “Venere” [Venus] (1938-40) and the last work by Cavaliere, “Grande pianta Dafne” [Large Plant Daphne] (1991). Contextualizing my analysis within the frame of their complex artistic, professional, and personal relationship, I demonstrate how Marini continued to inform Cavaliere’s work for years after his death, and that the idea of the ‘feminine’, in its ambivalence, was for both artists a subtle and powerful catalyst to address the complexity of the world.

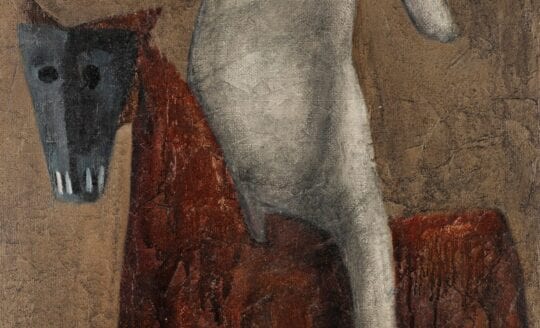

In Between Homage and Parody: On Relationships Between the Practices of Bahman Mohassess and Marino Marini

Bahman Mohassess (1931–2010) is from the generation of Iranian artists who traveled to Italy in the 1950s to study at Italian academies. Mohassess spent time in the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome, and after returning to Iran in the 1960s, he played a prominent role in the new Iranian art scene. Although he was not Marino Marini’s pupil, Mohassess’s practice demonstrates a special relationship with Marini’s art. In this essay, Mohassess’s artistic strategies are examined in the context of Iranian art in the 1960s and in terms of Marino Marini’s practice. Marini’s dialectical approach creates a route for Mohassess to problematize the descriptive qualities of figurative painting, which results in the confrontation of Mohassess with currents of abstract painting in Iran and their socio-political implications.