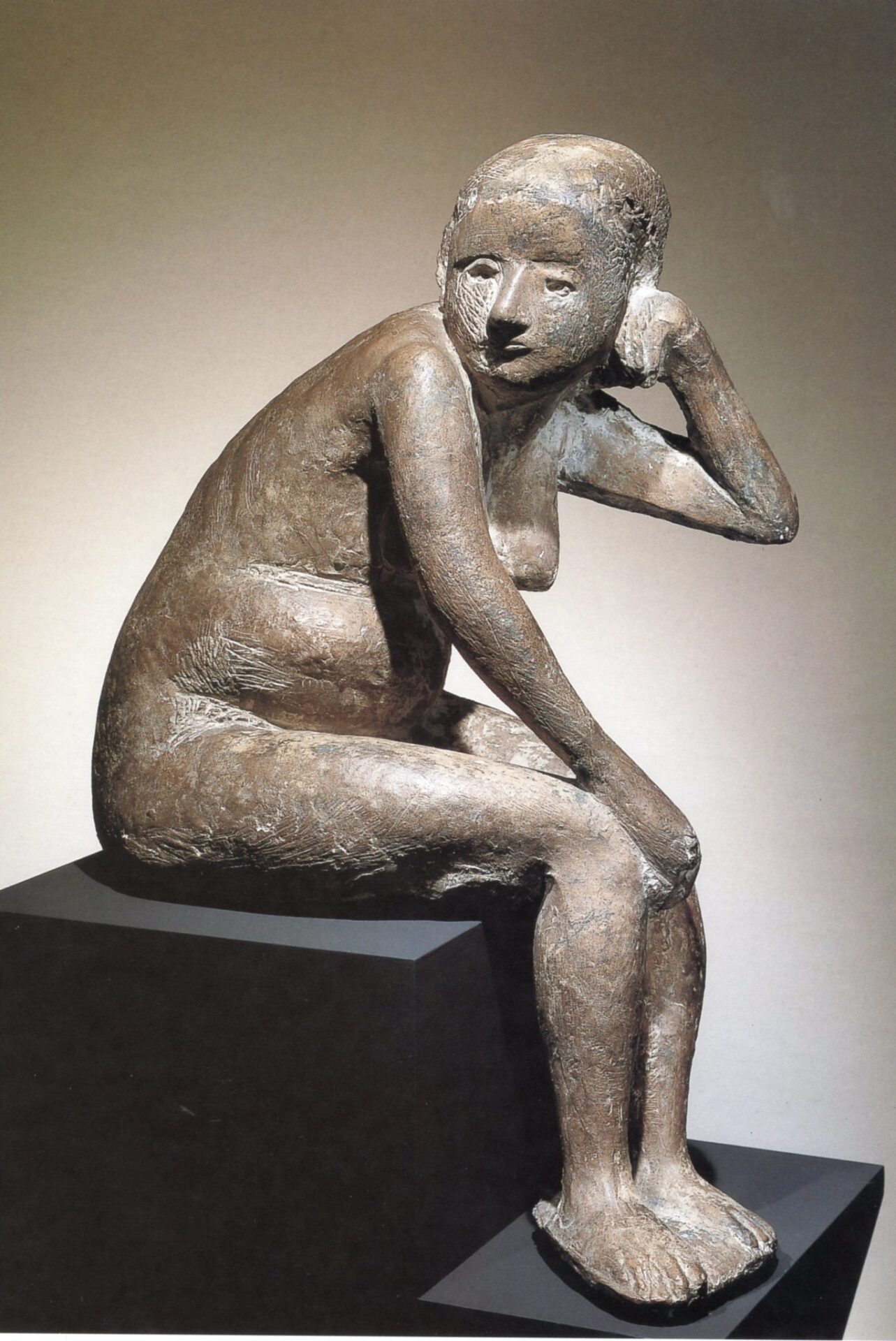

‘Susanna’ (Susanna) is the title of a fascinating sculpture by Marino Marini that is on view here at CIMA as part of the Marino Marini: Arcadian Nudes exhibition [Figure 1].

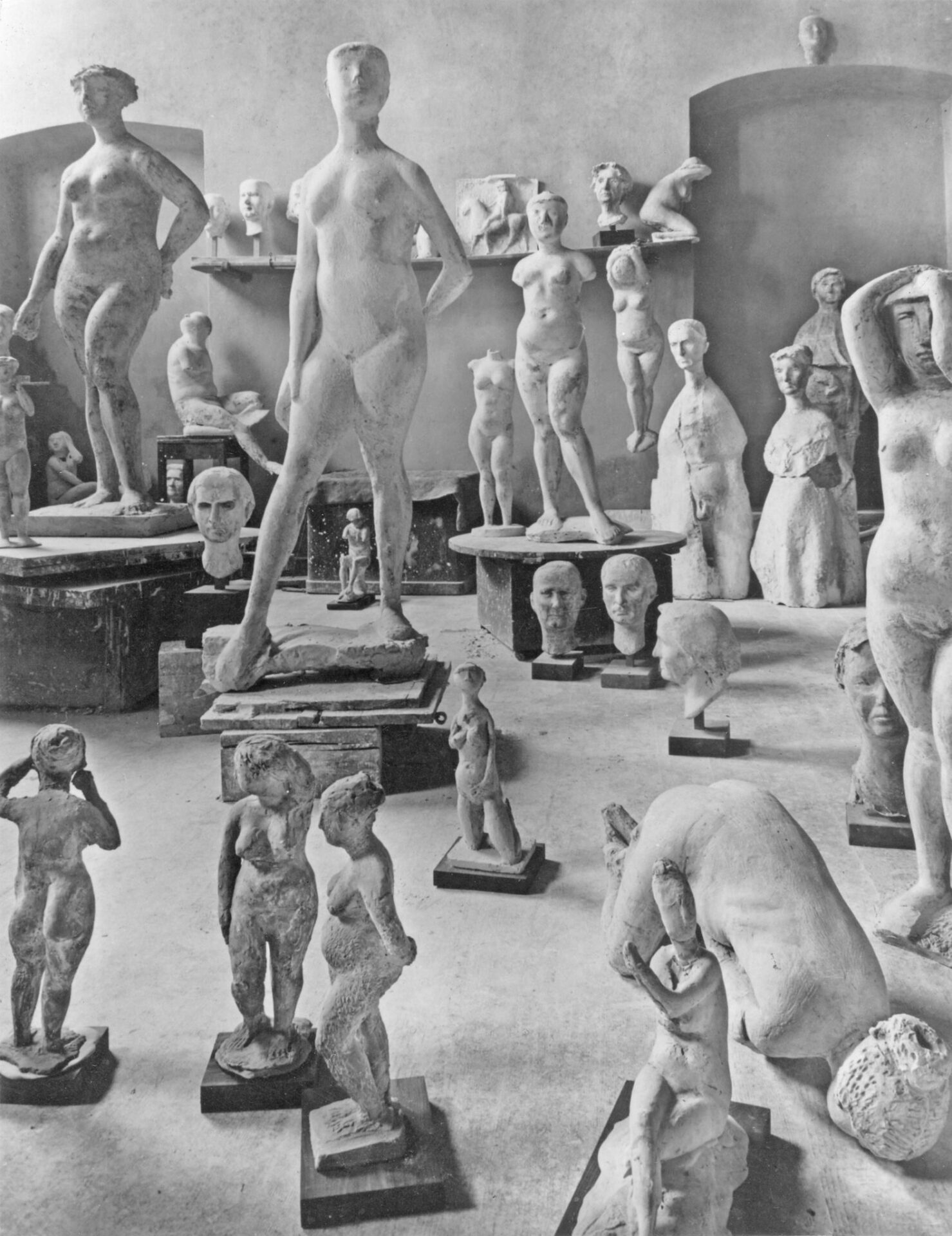

Cast in bronze after the Second World War, its plaster was conceived in 1943 during Marini’s self-imposed sojourn in the village of Tenero-Locarno, in Switzerland (his wife’s native country), to escape the Allied bombings that shortly afterwards would destroy both his Milanese house and his studio in nearby Monza. Surrounded by the peaceful Alpine environment, Marini would spend three and a half years there, from December 1942 till spring 1946, giving rise to one of the most fertile and creative periods of his career, as documented by a picture taken by the Austrian sculptor Fritz Wotruba [Figure 2].

It shows Marini’s small studio in Tenero populated by various artworks, above all portraits, little horses and female nudes, the latter being his favorite subject from the early 1930s, besides his most typical Nordic-inspired creations named ‘The Archangel’ (L’Arcangelo), ‘The Miracle (Gothic Cathedral)’ (Il Miracolo [Cattedrale gotica]) [Figure 3] and ‘Juggler’ (Giocoliere).

‘Susanna’ — alongside its counterpart-sculpture ‘The Bather’ (Bagnante) [Figure 4], alternatively called ‘Susanna II’ (Curt Valentin Papers, MoMA Archives, Series IV: Photographs, folder IV.57) — embodies one of his most enigmatic

works of the exilic period, which were almost exclusively done in clay and plaster rather than the more expensive cast in bronze.

The title possibly bears reference to the biblical story of Susanna and the two Elders included in the Book of Daniel. Trapping Joachim’s wife alone while bathing in her garden, the elders attempted to rape her, intending to blackmail her if she refused their advances. Susanna rejects them and is slandered to death, until the truth is brought to light by Daniel himself.

Whether intentionally or not, Marini’s young girl seems to be taken by surprise, too. The sudden movement of her naked body adorned only with a ring, and

precariously posed on a wooden base, as well as the slightly blurred surfaces, betray a state of ambiguous anxiety, that overturns the reassuring stillness and pre-classical naïveté of Marini’s prewar works. Other plastic details help convey the humanity and fleshy consistency of this solitary figure, accentuated by the self-absorbed expression upon her face, the naturally rounded back that shifts her weight forward, the pronounced breasts, the prominent belly, the protruding ribs, and the hair tied up [Figure 5 a, b].

Its cultural tradition and iconography are deeply rooted in late-Renaissance and Baroque art, especially of northern Europe — from Lucas Cranach the Elder (Giuseppe Marchiori, Scultura italiana moderna, Venice: Alfieri Editore 1953, 29) to Rembrandt (Lester D. Longman, Foreword, in Fifth Summer Exhibition of Contemporary Art, exh. cat. Iowa, State University of Iowa, June 15-August 7, 1949), as evidenced by coeval critics and journalists. But its emotional outcome and plastic style of disproportionate shapes and corroded surfaces were strongly influenced by Marini’s personal contacts and exchanges with other émigré artists and Swiss residents during World War II, such as Germaine Richier, Otto Bänninger, Hermann Haller, and Wotruba, with whom he closely associated in those years, taking part in group exhibits in Bern and Basel.

In his 1944 monograph on Marini, the Swiss-based philologist Gianfranco Contini introduced him as “a poet of surfaces,” stressing “the strictly figurative and extra-literary nature” of his latest characters, as opposed to those, for example, of Arturo Martini and Giacomo Manzù [Figure 6], who had already dealt with the same subject matter.

Some critics and photographers in the aftermath focused on this brand new meaning given to Marini’s vibrant surface textures, filled with “nostalgic pathos,” (‘pathos nostalgique,’ G.Contini 1944, VII) “homogeneous expressionist vision” (‘unità di visione espressionistica,’ G.Marchiori 1953, 29) and “esthetic vitality” (L.D. Longman 1949), wide-spreading a more intimate and existentialist interpretation of his sculptures, clearly to be understood as a resistance (Widerstand) to the phenomenon of fascism and as a reaction to the war drama. C. Ludwig Brumme, referring chiefly to Susanna, spoke about a “sad world” which Marini’s figure contemplates, “a subtle but forceful comment on our failure to assert the nobler side of man when the pattern of history so clearly demonostrates its need.” (‘Contemporary Sculpture: A Renaissance,’ Magazine of Art 42, October 1949, 216).

‘Susanna’ enjoyed under this light great international success since its creation: first presented at the 1944 collective exhibition in the Kunstmuseum Basel (Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz, October 14 – November 26, cat. no. 28), and one year after at the Galerie Aktuaryus in Zürich, it traveled overseas thanks to Marini’s first American merchant Curt Valentin, who exhibited it at the 1949 Fifth Summer Exhibition of Contemporary Art in the State University of Iowa (June 15-August 7), and at the first solo show devoted to Marini held in his New Yorker Buchholz Gallery in 1950 (February 14–March 11, 1950). Acquired in September 1954 by the art collector Joseph H. Hirshhorn, ‘Susanna’ was gifted ten years later, in 1966, to the homonymous Museum in Washington D.C., becoming part of its renowned collection.

IMAGE CAPTIONS:

Figure 1. Marino Marini, ‘Susanna’ (Susanna), 1943 (cast 1946-51). Bronze, 28 7/8 x 21 1/8 x 10 5/8 in. (73.3 x 53.7 x 27 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Figure 2. Fritz Wotruba, Marino Marini’s studio in Tenero, 1945. black and white photo, Archivio Fotografico of the Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia

Figure 3. Marino Marini, ‘The Miracle [Gothic Cathedral]’ (Il miracolo [Cattedrale gotica]) 1943. Polychrome Plaster and collage, 27 9/16 x 14 61/64 x 11 27/64 in. (70 x 38 x 29 cm). Brera Art Gallery, Jesi Collection, Milan

Figure 4. Marino Marini, ‘The Bather’ (Bagnante), 1943-44 c. Plaster, 23 45/64 x 19 11/16 x 11 21/32 in. (60.2 x 50 x 29.6 cm). Marino Marini Foundation, Palazzo del Tau, Pistoia

Figure 5 a / b. Marino Marini, ‘Susanna’ (Susanna), 1943. From Vingt Sculptures de Marino Marini présentées par Gianfranco Contini, Lugano: Collana di Lugano 1944, plates 2, 3.

Figure 6. Giacomo Manzù, ‘Susanna’ (Susanna), 1937. Wax, height 19 3/32 (48.5 cm). National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome