My 2014-15 CIMA fellowship was devoted to studying the American reception of works by the Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso. One of the most interesting stories concerned the Rosso sculptures bought by Lydia Winston Malbin in the early 1960s.

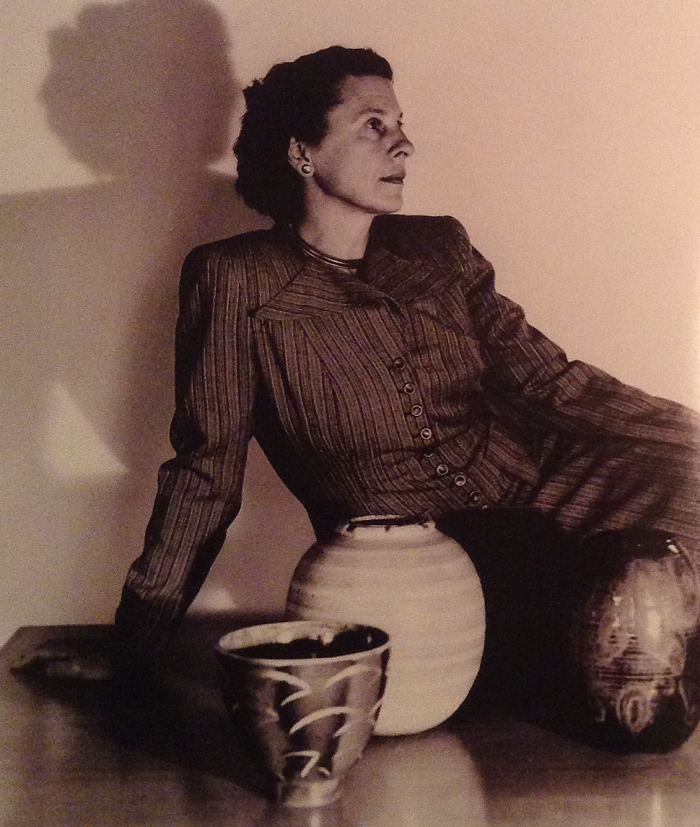

Lydia Winston Malbin (1897-1989) was the daughter of Albert Kahn, the well-known industrial architect who designed the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant in Detroit, among other important industrial buildings in the United States and abroad. She began to collect modern European art in the late 1930s, and over the course of two decades assembled one of the major collections of Futurism—including artists such as Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, and Gino Severini. Medardo Rosso was an artist beloved by the Futurists, especially by Boccioni, and this likely explains how this 19th-century sculptor became part of the Malbin Collection.

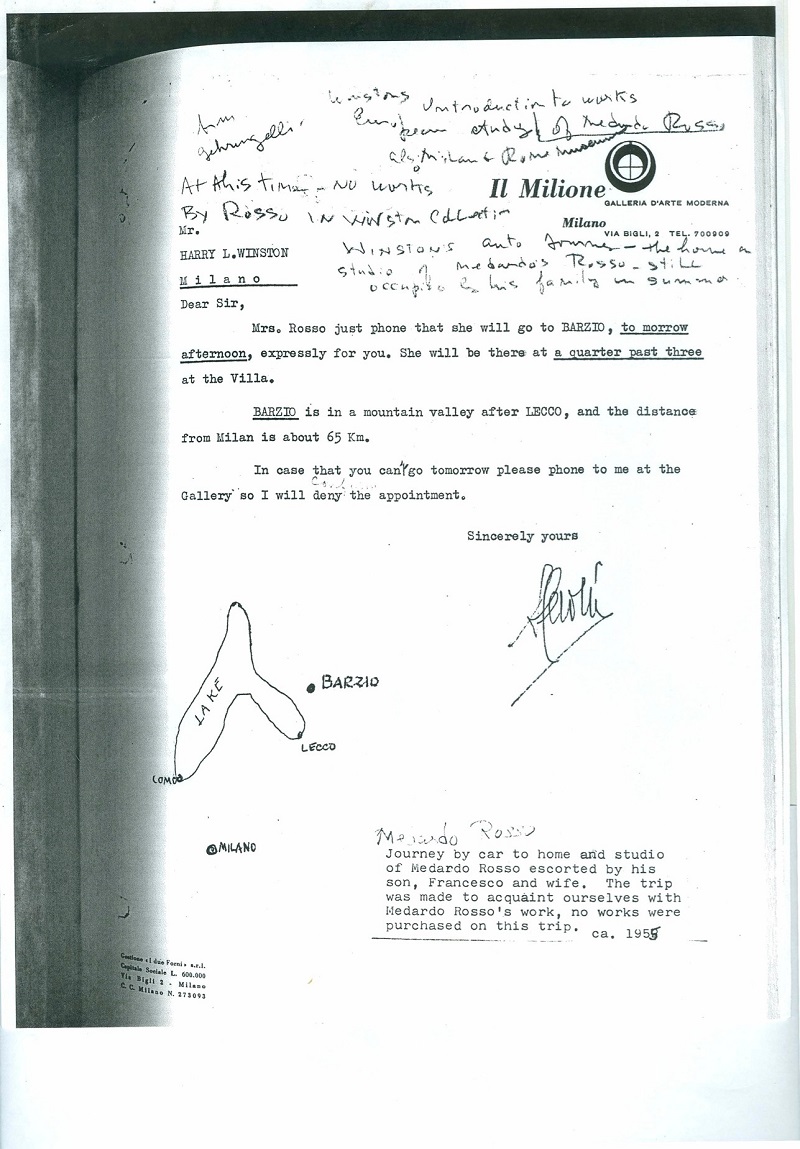

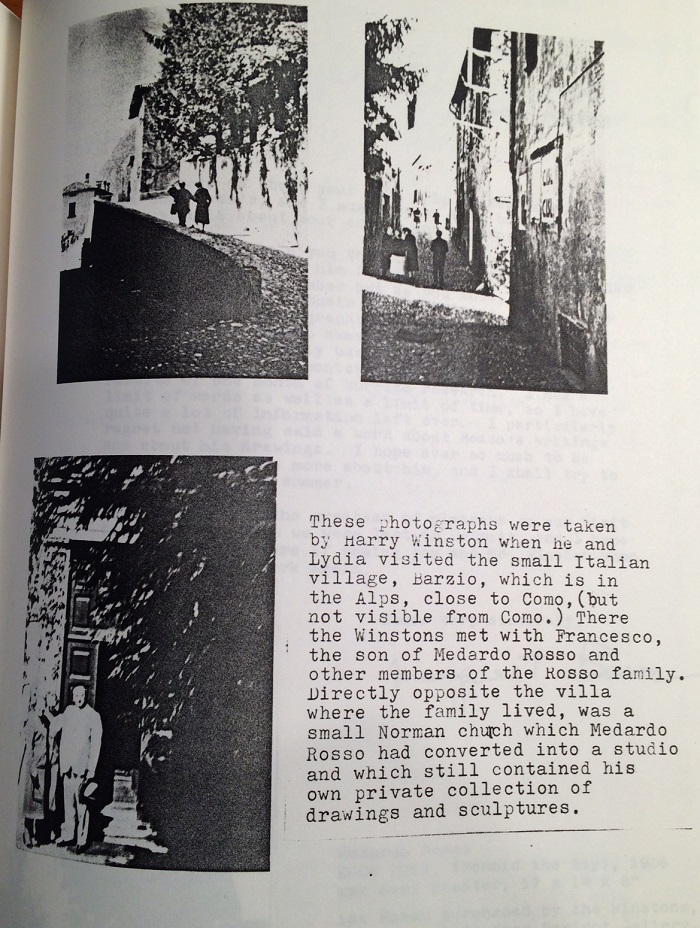

In 1955 Lydia Winston [her second husband was named Malbin], on a trip arranged by the Il Milione Gallery of Milan, had the opportunity to visit the home and museum of Medardo Rosso in Barzio, near Lake Como. Francesco Rosso, the son of the artist, and his wife welcomed her. Even if no works were purchased on this trip, the journey acquainted her with Medardo Rosso’s sculpture.

It was 1960 when Lydia Winston bought her first Rosso: a wax version of Ecce Puer (Behold the Child). She traveled from Detroit to New York City and back in one day, just to see this sculpture, which was on exhibition at the Peridot Gallery. Peridot, a commercial gallery directed by the dealer Louis Pollack, had just held the first Rosso solo show in the U.S.

These years of the late 1950s and early 1960s were crucial ones for the fortunes of Medardo Rosso in the United States. Lydia Winston’s interest in Italian modern art and in Rosso in particular was fostered by Alfred Barr Jr., founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, and his wife Margaret Scolari Barr, the Irish-Italian art historian and teacher. Scolari Barr published, in 1963, the first monograph in English on Rosso. She also encouraged Lydia to buy in October 1963 four additional works by Medardo Rosso: a bronze of the Man in Hospital, a wax of the Jewish Boy, a wax of The Flesh of Others, and the wax version of the Sick boy (fig. 5) that is currently on view at the Center for Italian Modern Art. All of these sculptures were purchased in Amsterdam from a Miss Osterkamp, who was heir to the estate of Etha Fles, the collector, backer-promoter, and lover of Medardo Rosso who played such an important role in the life of the sculptor.

If we situate this episode within the Italian contemporary art scene in the United States, and New York in particular, we can glean additional reasons for this emerging interest in Rosso’s work. American interest in Italian art and culture was rekindled in the 1950s, with the end of the war, the Marshall Plan, and active tourism promotion. This interest came to encompass contemporary art, and consequently the US-Italian art market was no longer restricted to the Old Masters. Among New York’s commercial galleries, the Rose Fried Gallery, the Martha Jackson Gallery, the Catherine Viviano Gallery, The Buccholz Gallery (then the Curt Valentine Gallery), and the World House Galleries all promoted contemporary Italian art. Within this context, Italian sculpture garnered almost equal attention to Italian painting. From 1945 to 1955 the Museum of Modern Art secured several three-dimensional Italian works. In 1949 the museum acquired an Arturo Martini (a sculptor who was almost entirely unknown in the US) along with a Lucio Fontana ceramic, a Marino Marini bronze, and an Alberto Viani marble. In 1956 MoMA bought Giacomo Manzù’s Portrait of a Lady, cast the year before. Some of these sculptures were exhibited in 1949 in Twentieth-Century Italian Art. As Barr underlined at the show’s close, they were an enormous success: “Many visitors to the current exhibition have felt that the recent Italian sculptors surpassed the painters.” (Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers, The Museum of Modern Art Archives)

Of course, Medardo Rosso was an artist belonging to a previous generation; he was born in 1856 and he died in 1928. However, as the Chairman of MoMA Collections James Thrall Soby pointed out in a letter of 1958:

“It’s worth remembering that … Italian art is very chic at the moment. … Americans all over the country have been buying contemporary Italian paintings and sculpture left and right since the war. As an example, a very old friend of Melissa’s and mine just wrote she had bought three paintings from [Gaspero] Del Corso; I don’t think she had ever bought a picture before in her life.” (James T. Soby Papers, The Museum of Modern Art Archives)

At the end of the 1960s, the richness and depth of this American collecting of Italian modern art can also be seen in the number of works that MoMA sent to Italy in 1960 for the exhibition, Italian Art from American Collections (fig. 9). The show, which was made up mostly of loans, comprised more than 150 works, including paintings and sculptures. Medardo Rosso was not exhibited, but his name appeared in an early list of loans, dated October 1, 1959, that Soby compiled for the show. Soby was clearly interested in the artist. I found a fascinating letter in the MoMA archives that he wrote on June 14, 1958:

“My hunch is that somewhere in America there are sculptures by Medardo Rosso, probably belonging to people of the older generation. Rosso worked in Paris for a while and was almost certainly known to Mary Cassatt’s American circle.” (James T. Soby Papers, The Museum of Modern Art Archives)

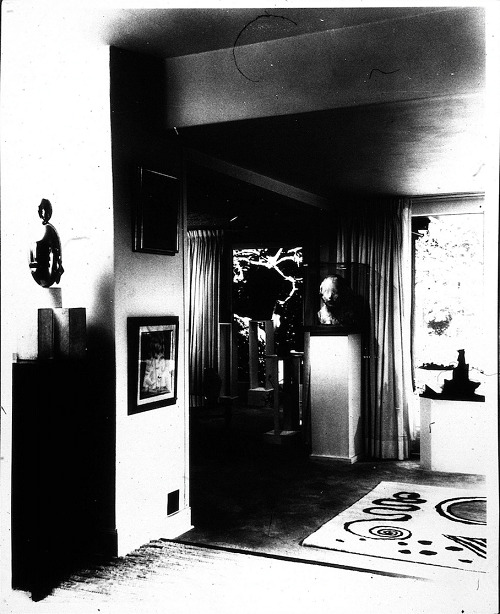

This statement offers the first evidence of any American interest in Medardo Rosso. Years later, the relevance of Medardo Rosso’s work to an American audience found a suitable demonstration in the solo show the Museum of Modern Art devoted to this Italian artist in 1963, the first museum show on Rosso in the United States. It was the same occasion in which Lydia Winston Malbin exhibited for the first time the Rosso sculptures in her collection.

Interested in learning more?

Watch a video of Chiara talking about the Bambino Malato sculptures at CIMA.

The Malbin Collection papers were microfilmed by the Archives of American Art.

There are Lydia Winston Malbin papers related to her collection at the Yale University Beinecke Library.

Read Deborah Goldberg’s 1986 interview with Lydia Winston Malbin for Vassar Magazine.

Read Lydia Winston Malbin’s New York Times obituary of October 18, 1989.