“Io non lavoro per i miei contemporanei, lavoro per il futuro” (I don’t work for my contemporaries, I work for the future.) —Medardo Rosso

Currently on view in London is a show at the Waddington Custot Galleries exploring the role of photography in the practice of three sculptors: Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brancusi, and Henry Moore. The relation between sculpture and photography is an idea that is certainly in the air right now. Last spring the Museum Boijmans van Bueningen in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, hosted an exhibition entitled Brancusi, Rosso, Man Ray: Framing Sculpture, which brought together sculptures and photographs of the sculptures by these three artists. And on view now at the Center for Italian Modern Art, through June 27, is the first exhibition in the United States to highlight the extraordinary experimental photographic practice of Medardo Rosso, featuring nearly sixty photographs alongside Rosso’s sculptures and drawings.

Medardo Rosso was ahead of his time, and he knew it.

He was a photographer himself, because he knew that professional photographers weren’t able to properly see his work, to understand and represent it. Their traditional studio methods were not appropriate for his sculptures—so modern, shaped by light and shadows, requiring one single best point of view to be appreciated.

He also cast his works himself, rather than use a professional foundry like Rodin and other Parisian sculptors did, because he couldn’t entrust the realization of his sculptures to someone else. For Rosso all the material phases of the creative process were intimately intertwined with the concept itself.

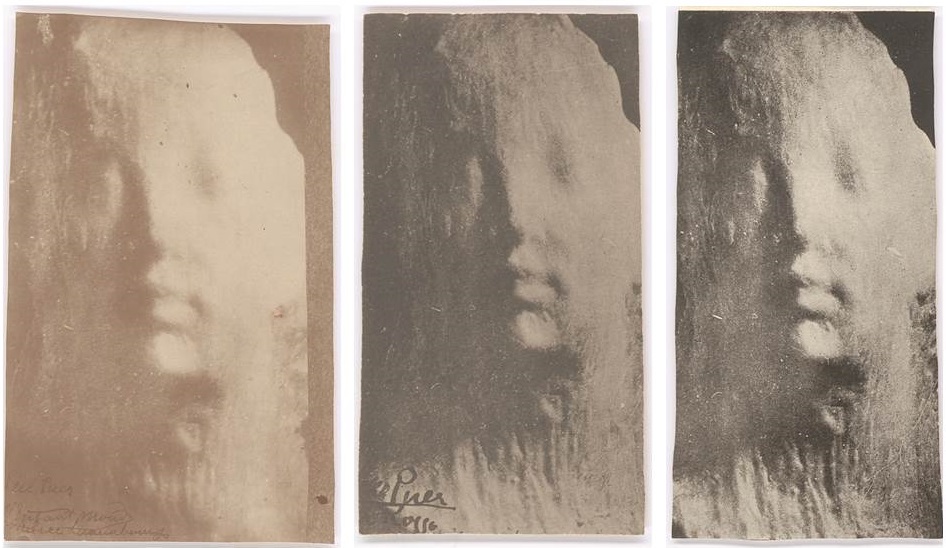

Both in sculpture and in photography he worked intensely on repetition and serialization, thinking and rethinking the same subject matters in varied materials (wax, plaster, bronze and for his photography using many kind of papers, different exposures,and different chemical processes for the development).

Among his contemporaries there were other artists—painters in particular—working on the idea of the series, that is also to say exploring a theme in its many various iterations. The best known of these is probably Claude Monet, with his Rouen Cathedrals, his haystacks, and his water lilies.

We can imagine how hard it must have been in the context of the second half of the 19th and the early 20th century for people to deal with Rosso’s photographic series. Here was the new language of photography being used in an extremely experimental way—one that strikes us as contemporary even today.

Today we are his future. And we have new methodological and interpretative tools—developed during the last one hundred years or so, in order to understand the avantgardes of the early 20th century, Pop Art, and conceptual art—with which to understand how truly groundbreaking Rosso was.

We are living in the age of mechanical reproduction, as predicted by the great thinker Walter Benjamin. We know how art can work on multiple copies and serialism; we are familiar with a widespread proliferation of icons; and we know the strong impact of mass media and digitization. Photoshop has made practices of cutting and pasting and endlessly editing familiar to millions of people on the planet. Tongue in cheek, we could say this is the post-Andy Warhol era…

Rosso’s photographs were (are) finished and independent works of art. At the same time, they were born from a substantial connection with his sculpture; they offer a way of exploring it at another level. And a way of enlivening the sculptures, too.

The case of the Rieuse is singular in Rosso’s photographic panorama: he realized a dynamic sequence of five pictures by just slightly moving the sculpture from one snapshot to another.

Thanks to a recent visitor to CIMA, illustrator and graphic artist Jonathon Rosen, the Rieuse sequence has come to new life. Rosen, one of the authors of the forthcoming Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema, was inspired after his visit to the Rosso show to animate this series, thus revealing its great cinematic potential. Now the movement is not in our eyes only any longer, as it was when we looked at the five separate images.

Medardo Rosso’s photographic investigations and series are no longer so disconcerting or obscure for 21st-century people. Yet they nevertheless remain mysteriously fascinating, having kept through time all the pioneering strength of works conceived by a visionary artist who was able to foresee the very modern idea of visual representation through repetition.