Read on for a deep dive into 3 of the artworks included in Marino Marini: Arcadian Nudes (on through June 13, 2020).

– Venere, 1942

Our first stop on this descriptive tour, Marino Marini’s bronze Venere (Venus), cast in 1942 was created to represent a timeless, serene, and tranquil sense of order and balance. The Roman goddess Venus encompasses love, beauty, desire, sex, fertility, prosperity, and victory. Focusing on these characteristics while creating this sculpture, Marini’s result is a rounded and archaic figure as opposed to slender and elegant forms that defined the Classical style. Marini focused on the idea of fertility and prosperity while creating his female figures: the Venus is not sexualized but appears earthlier and more fertile with her shapely curves and swelling belly, alluding to the ideas of hope and regeneration.

It is interesting to note that from the late 1930s on, the amount of female figures produced by Marini increased, perhaps because during that time Italy and Europe were heading for war and hopes for the future became more prominent in the lives of Italians.

‘My nudes … also have, I believe, a classical quality of anonymity. I have tried to express in them no personal sensuality of my own. I wanted to exclude from them the autobiographical element that allows us to recognize, in sculptures of Renoir or even Maillol, the artist’s own mistress or at least a particular contemporary type of feminine beauty that appealed to the sculptor more immediately than an eternal type of classical beauty.’ (Marino Marini, quoted in S. Hunter, Marino Marini – The Sculpture, New York, 1993, p. 171).

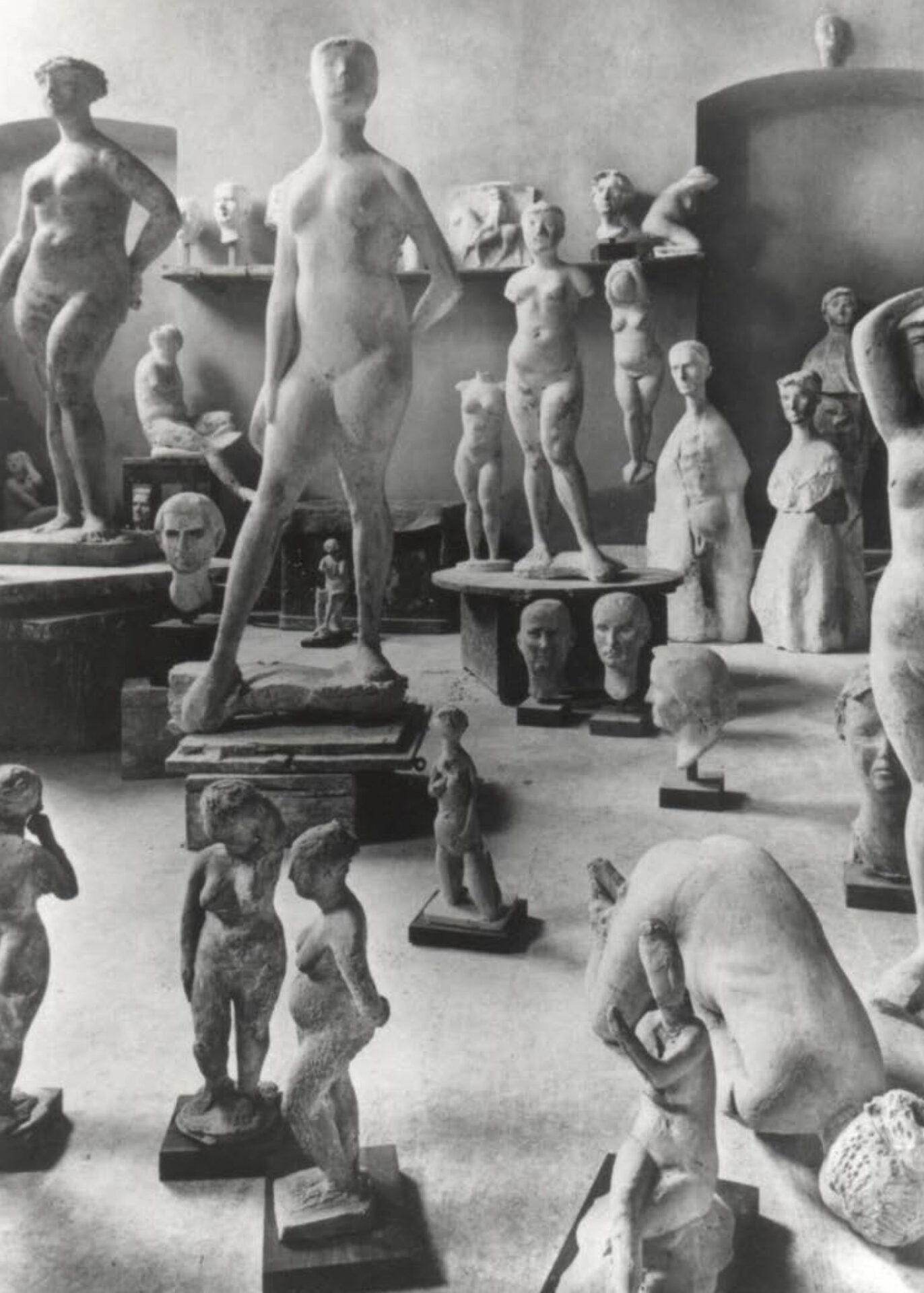

Laura Mattioli, co-curator of this exhibition, adds” This sculpture has an unusual size, it is 110cm tall (43″): it is therefore neither a natural size figure, nor a ‘miniature,’ small bronze–fitting within the Renaissance tradition. Another piece, similar in size and pose is visible in the center, between two natural-size sculptures, in the photo taken in 1945 in Tenero (Switzerland) by Fritz Wotruba, depicting Marini’s studio.

In curating this exhibit, CIMA willingly re-proposed the juxtaposition of sculptures of different sizes, which Marini used to do in his atelier. The unusual dimensions of certain figures highlight their reality of artistic inventions and their distancing from any intention of mimesis of reality–in a space which therefore becomes purely imaginary and surreal.”

– Composizione, 1943:

One of two reliefs in CIMA’s exhibition depicting Ancient Greek subjects, this bas-relief composition is of the Three Graces.

While at first glance, one recognizes the three nude women to be those of the Greek human incarnations of positive qualities, upon further investigation, one finds that the women are considerably different from the exemplary image of this antique trope. Marini’s central Grace does not turn her back towards to the viewer as is traditionally done with Greek representation. Instead, she is positioned facing the viewer. She covers her head, perhaps in frustration.

The Grace on the right also stands facing directly out towards the viewer, and, like the central Grace, abandons the classically predictable S shape of the body with both feet firmly grounded, almost confrontationally.

In comparison to the ideal of visually pleasing Graces, Marino’s Graces appear rough and unpolished. Another aspect of this relief which draws a line between the modern and the antique can be found in the high heels that the otherwise nude Graces are wearing.

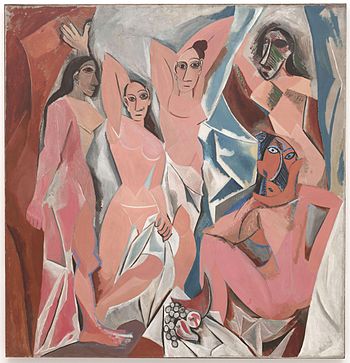

These women do not solely pay homage to the ancient Three Graces, but also project their modern divergence from classical female nudes. Co-curator Laura Mattioli adds “These are an evident fetishistic reference, and a connotation frequently used by painters at the beginning of the century to indicate a prostitute (for

example in Mario Sironi’s Venere dei Porti, which was part of last year’s CIMA exhibition). In this case, the anti-classical treatment of the figures indicates another source and a different meaning of the depiction, deriving from Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Looking more attentively, one can note that the first figure on the right wears tight-fitting hosiery, of which we see a V-neck outline on her chest, and the armhole, while the other two seem to be caught in the act of disrobing from a dress or blouse, with their arms elevated.

These rather ungainly gestures, reveal ponderous bodies and unnatural torsions that contract any possible identification with the Three Graces, and transform the composition into a much more contemporary theme, close to the images that were being painted in Paris in the XXth century.”

– Piccola Danzatrice, 1944:

1944

bronze

23 3/8 x 9 x 6 ½ in.

(59.3 x 22.9 x 16.5 cm)

Fondazione Marino Marini – Pistoia

Laura Mattioli observes, “This piece is titled Piccola Danzatrice (Small Dancer) since its inception and oldest publications. It is part of a group of three sculptures realized between 1943-44 and 1949, depicting a seated woman with crossed legs, and an arm above her head. The sculptures seem to develop the same idea in three phases. The first (Fig. 237 in Marini’s general catalog) is a high relief in contrast with the other two, of small dimensions and made up with a cursory modeling; the second, exhibited at CIMA becomes an all-round sculpture, well-defined in the twisting motion of her volumes, although still in direct relation with the supporting wall for the wooden structure–most likely designed by Marini–that sustains her. The third (Fig. 320 in the general catalog), is a later work of 1m 20cm height (47″) is supported by a

column-shaped pedestal and sets itself as a standalone element in the space. While the small bronze at CIMA is characterized by a lateral point of view that accentuates the dynamism of the juxtaposition of volumes, the last version, albeit almost identical, shifts attention to the overall equilibrium.

The subject of this sculpture seems to be a resting ballerina, rather than a dancing one. Around the invention of the image different models converge, like Degas’ Ballerinas and Toilettes.” Marini’s tryst with the female nude is inspired by Pomona, the Etruscan goddess of fertility who became, for Marino, the symbol of a rural, harmonious and peaceful world. Like Degas’ dancers, this is a movement piece, sensual and spirited, and can only stand upright this way with the wooden support Marini himself designed. In the making of this bronze, Marini alternated between different visual suggestions.

On one hand, it is essential to mention the reference to Indian art (the sculptures of the Temple of the 64 Yogini of Hirapur) proven by the prosperous opulence of the woman’s breasts and the position of the lower limbs. On the other, the ample volumes in the piece call to mind the vigorous female figures created by Henry Moore.

For Marini, as with his other nudes, this figure was one embedded with the entirety of the female figure, and

rooted deep in classical themes. “My ‘Pomone’ live in a bright world, with their sunny disposition, full of humanity, of abundance, and of great sensuality.

They represent a happy season that breaks the tragic time of war. in all these images, femininity is enriched with all its past meanings, those most inherent, most mysterious: a sort of unavoidable necessity, of unmovable stillness, of primitive and unconscious fertility.”

(as quoted in the exhibition text of ‘Marino Marini, Painter, Draughtsman, Sculptor’, Museum de Fundatie, September 2013 to 16 March 2014).