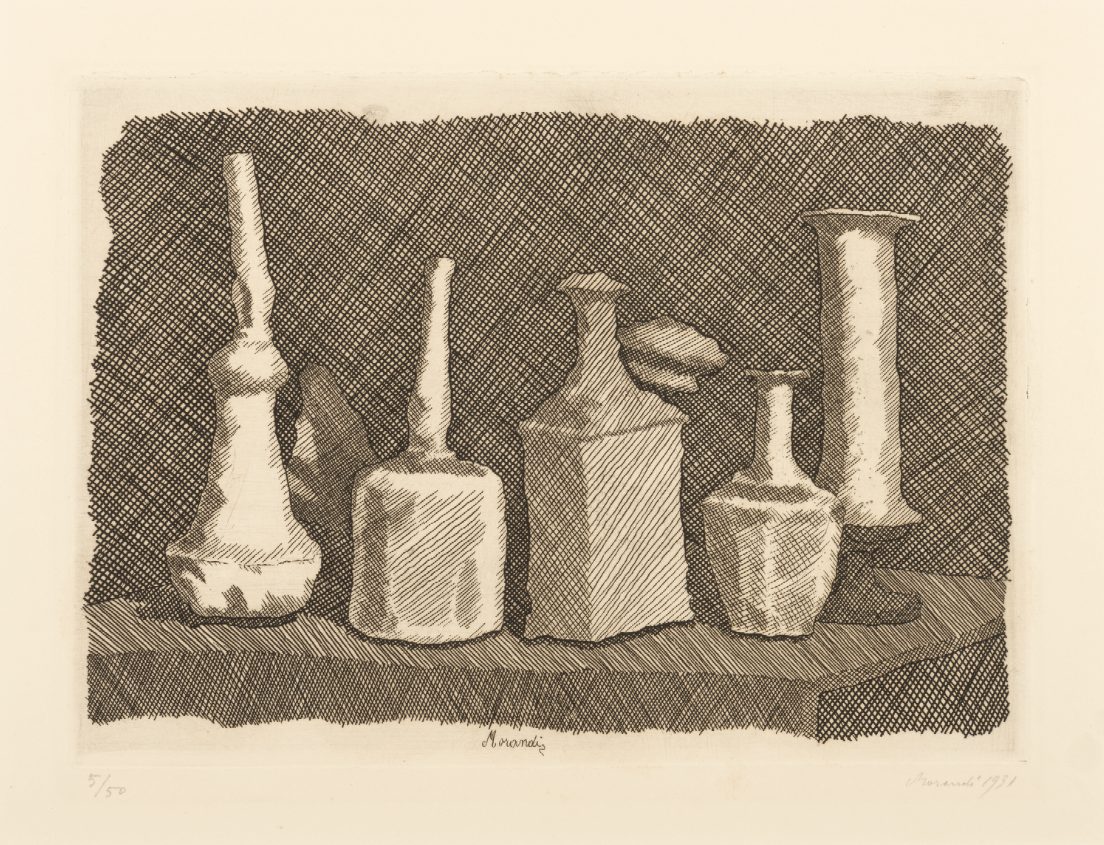

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1932, oil on canvas, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Roma (Vitali 170)

The Center for Italian Modern Art selected Giorgio Morandi’s Still Life, one of the masterpieces in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome, to be part of its Giorgio Morandi exhibition this season. We are pleased to have received an essay written about the work from one of the experts at the museum, Maria Catalano. The original Italian version can be read here. For our blog, we have prepared an edited translation in English.

Giorgio Morandi was born in Bologna, where he spent most of his life. In his studio, his worktops, panels, and objects—the bottles, jugs and cups that are present with subtle variations in all of his paintings and engravings—are still preserved.

Morandi’s artistic production is the result of the silent, methodical, and almost stubborn work of an artist who considered his art the only reason for living and the preeminent expression of inner spiritual searching. The natura morta, or still life, assumed a great importance in the Italian painting tradition in the twentieth century. The first modern painters recreated la forma delle cose (the shape of things) through the careful observation of objects—the trivial detritus of everyday life—by arranging them precisely in the studio, under particular and considered conditions of light.

It is not a coincidence that in the 1920s and 1930s, when the rhetoric of the Fascist regime influenced every aspect of social life, including the arts, the preference for an artistic genre devoid of ideological and celebratory content became an affirmation of the artist’s autonomy. It is through this lens that we can interpret Giorgio Morandi’s paintings and etchings from the 1930s. The Bolognese artist was extremely talented in etching, a complex technique requiring great skill in balancing etching acid and a dense network of marks. By eluding the voluptuousness of color, his engravings convey thoughtful observation of the objects through the dramatic contrast of black and white.

The Galleria d’Arte Moderna’s Still Life, which is the only painting among a small but significant holding of etchings from the early 1930s, belongs to Morandi’s mature period. Emerging out of his Metaphysical phase, this work reveals a greater intensity, poetic search, and grasp of the profound essence of things through the representation of forms as volume and color. In this artwork, as in many others of the artist’s mature period, the objects lose their contours; their forms melt, becoming immaterial subjects. The result is an assimilation of the objects to shadows, without however losing touch with reality. By using calibrated spatial arrangements and refined color compositions, Morandi rooted his works profoundly in reality, while also imbuing them with his broad cultural understanding and his meditative and comprehensive knowledge of the European painting tradition.

In this Still Life from the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, a desire for harmony between the immediacy of the visual sensation and the depth of the observation is palpable. This desire mediates the detachment from reality, creating a tension undoubtedly linked to the cultural debates of those years, especially the value of tradition and a dialogue with the antique.

Morandi, with strength and autonomy, inserts this and other works into a broader artistic milieu, which only a partial view can link solely to the political propaganda of the Fascist regime. Even though, the intentions of the rising regime to create a propagandistic national art started to outline in those years, the theory of the ritorno all’ordine did not interfere with the eremitic research of the Bolognese artist.

Far from clamor, controversy or easy success, Morandi participated in the Quadriennali Nazionali of 1931 and 1935. The exhibitions, organized by the regime at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, consisted in a comprehensive representation of the Italian artistic production, exhibiting the most prestigious artists of the time. Both in 1931 and in 1935, the Governatorato of Rome acquired for its “contemporary works” collection – inaugurated in the Capitol as Galleria Mussolini in 1931- the Still Life and the etchings held today in the collection of the Galleria d’Arte Moderna.

In the early 1930s, Rome represented for the regime not only the political and administrative capital city, but also the capital of the arts. The Galleria Mussolini was, indeed, to take the role of National Museum—becoming, by the number and value of acquisitions, highly representative of contemporary Italian art. Even those isolated acquisitions, such as the Still Life by Giorgio Morandi, do not cease to surprise us today for their artistic value, along with works such as The Family by Mario Sironi, The Combat of the Gladiators by Giorgio de Chirico, Renato Guttuso’s Self-Portrait of 1937, Arturo Martini’s Shepherd, or Marino Marini’s Bather.

In 1938, by order of the Fascist state, the Galleria Mussolini was closed and most of its representative works were transferred to the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, considered the only institution appropriate for documenting the state of contemporary art. Morandi’s Still Life formed part of that transfer. Although it returned only recently to the collection where it first belonged, it has never ceased to feature in the most important national and international exhibitions dedicated to the artist.

—Maria Catalano, Rome 2015