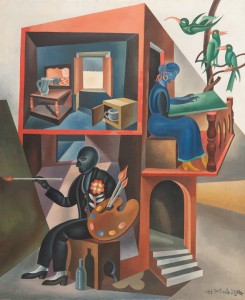

In 1940 Depero wrote these lines about his painting, Io e Mia Moglie (I and My Wife), one of the only self-portraits he ever made: This painting is one of the first examples of a ‘psychological portrait.’ It was conceived in Viareggio in 1918 and finished in Rovereto in 1919. Made and inspired by the house that I lived in in the Tyrrhenian city. My wife in blue stitching on the balcony, with three arms, showing the constant activity of a housewife. The bedroom is open to light and intimacy. In the foreground is the large painter, his colorful palette on his arm, in contrast to all his mournful figure of abject poverty, silent and sealed as if in a diving suit, obstinate in his constant dream of plumbing the depths of the imagination. A bottle of diluent or solvent at his feet, he sits on the stool and paints, inside the red house that is opened as if it were a magic box.

The artist wrote these lines many years after the execution of the painting, at a time when the disillusionment of maturity led him to rethink in pathetic terms his first glorious years of work.

Io e mia moglie is an important painting made at a decisive moment of Depero’s career, in 1919 when – after nearly six years in Rome – he returned to his native Rovereto and opened the Casa d’Arte Depero. Depero always wanted to exhibit this work, and it was included at the Palazzo Cova exhibition in Milan in 1921, and in later years could be found in Rome, Prague, and Berlin. The painting remains pivotal in Depero’s work because it is one of the very few self-portraits that he made (despite his big ego!), and its unique iconography is worthy of note. It is not a simple self-portrait. Although the artist is visible, he also includes his house and particularly his wife, Rosetta Amadori, the woman who remained by his side throughout his life, through all his travels in Italy and abroad.

Io e mia moglie is a painting executed by an avant-garde artist. The irrational sense of the space, the unnatural and vivid colors, the angular and stylized shapes, the fantastical multiplication of Rosetta’s arms—everything expresses Depero’s modernity. There is also the dreamy atmosphere typical of all his works, which probably derives from Henri Rousseau, an artist who met with great success in Italy in the early Twentieth century (Fig. 2).

Nevertheless Io e mia moglie gives the greatest insight into Depero’s deep interest in the art of tradition. Where we have already seen those unrealistic proportions between the figures and the architecture? And above all, where have we already seen a house represented without walls, sliced open like a box to reveal the scene inside? The answer, of course, is in the Italian painting of the fourteenth century. Think about the paintings by Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, or Ambrogio Lorenzetti. The comparison becomes most impressive if we think of Giotto. Take, among the many examples that we might choose, the Annunciation of Anna, one of the frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1303-1306) [Fig. 3].

The house without walls, the balcony, and the relationship between the figures and the architecture are the same. I do not know if this was the exact model for Depero, but it is certain that when Io e mia moglie was painted Giotto was a name that was being discussed among Italian avant-gardist artists. For Carlo Carrà, especially, Giotto had become indispensable since 1916, when Carrà moved from Futurism to embrace a totally different painting style with an archaic or medieval taste.

Today Io e mia moglie looks dramatically different from when Depero painted it in the fall 1919. If we look at photos Depero took in the early 1920s (now kept in the Depero Archives at MART in Rovereto) [Fig. 4], the design remains the same, but it is apparent that the original paint surface was flatter, devoid of the lights and shadows that we see today that seem to liven up the whole painting.

What happened? In the early 1940s Depero completely repainted the work. This took place around 1944, shortly before Gianni Mattioli acquired the work. Why? Io e mia moglie, like many other paintings of the same period, had traveled a lot, in Italy and abroad. As a result of these trips, the painting suffered damage and paint loss, requiring restoration only a few decades later.

Mattioli paid 5,000 lire for the painting. Interestingly, he paid an additional 10,000 lire for its restoration—which was probably at least in part an effort to help the artist have work in a period when he was struggling and not earning much money. In a letter dated June 18, 1944, Mattioli enthusiastically described the work that had just entered his collection: “I saw with great joy all these thy works. You know how much I like them; also retouching Io e mia moglie and the Selvaggetti is perfect. The fresh and bright colors with which you have been able to rejuvenate them, like a true magician, your technique and your own personal fantasy created two works that excite me as much today as many years ago, the first time I saw them. I am happy to be the lucky owner of all the drawings and paintings that you sent me.”

Depero is an excellent example of an artist who continued to define himself as “futuristic,” while, in reality, introducing in his work many references to the past. His work thus becomes a complex set of elements and styles: Futurism, Metaphysical Painting, “return to order,” Art Deco, etc. We see this so well in Io e mia moglie, which has all the solidity of an antique painting and shares similarities to paintings made by the artists that worked around the roman magazine “Valori Plastici” looking for a new art, an art far from the avant-garde experimentalism (Fig. 6).