Written by CIMA 2018–2019 intern, Nicole Boyd

The early 2000s were pivotal years for Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu. During this time the couple – already longtime partners in life, as well as in art collecting – relocated to Rome for a year and fell head over heels for the Italian avant-garde movement known as Arte Povera. Their passion for this area of visual culture incited a period of exhaustive research and collecting that, in essence, culminated with the founding of Magazzino Italian Art.

Magazzino is an exhibition space and research center in Cold Spring, NY, whose mission is very much akin to CIMA’s raison d’etre: the institution was established to promote greater awareness of Post-War and Contemporary Italian Art among American audiences and, particularly, to build an environment well-suited to display Olnick and Spanu’s collection of works from the Arte Povera movement. In fulfilling the latter objective, the couple is directly inspired by famed gallery owner Margherita Stein – a champion of Arte Povera who dreamed of creating a home for “her artists” in the United States (and, incidentally, was the subject of Magazzino’s first exhibition in 2017). On Thursday, May 16, CIMA’s members were invited on a private tour of this striking habitat for Arte Povera. Most traveled to the Hudson Valley, by train or car, from New York City – not a small trek; however, at the conclusion of this journey, all were rewarded with an afternoon of art-viewing and artful conversation, in a space, as idiosyncratically beautiful as the artwork it houses.

The facility of Magazzino is an inventive object of art in its own right. Once a computer manufacturing warehouse, the building was transformed by Spanish architect Miguel Quismondo from an L-shaped construction into a rectangle with a courtyard at the center. Its structural metamorphosis notwithstanding, Magazzino (which is the Italian word for “warehouse”) does not abandon its industrial origins. Quismondo’s project – which includes 18,000 square feet of gallery space, as well as an expansive library – pays homage to these roots in plain sight. Far from obscuring the original warehouse with updated architecture, his design celebrates the coexistence of the old and the new and – namely through the manipulation of natural light, as well as different building heights and shells – allows viewers to distinguish between the preexisting structure and the addition.

Against the backdrop of Cold Spring, Magazzino manifests as an outcast of sorts, a massive, gray-white structure whose hard edges and assertive solidity (at least in the warmer months) contrast starkly with the Hudson Valley’s lush, ephemeral greenery. Approaching the art warehouse from Route 9, visitors – CIMA’s tour group included – cannot help but be surprised by the structure’s façade. And inside, the visual spectacle persists.

Art greeted our tour group immediately as we stepped through Magazzino’s main entrance: Michelangelo Pistoletto’s 1933 Stracci italiani (Italian Rags) – an interpretation of the Italian flag in discarded fabric – hangs on a wall to the right, and its vibrant tricolor scheme demanded our (or at least my) gaze in the otherwise monochrome interior. Situated in the center of the lobby, an imposing Sfera di giornali (Sphere of Newspapers), also by Pistoletto, subsequently compelled us to move deeper into the building’s interior.

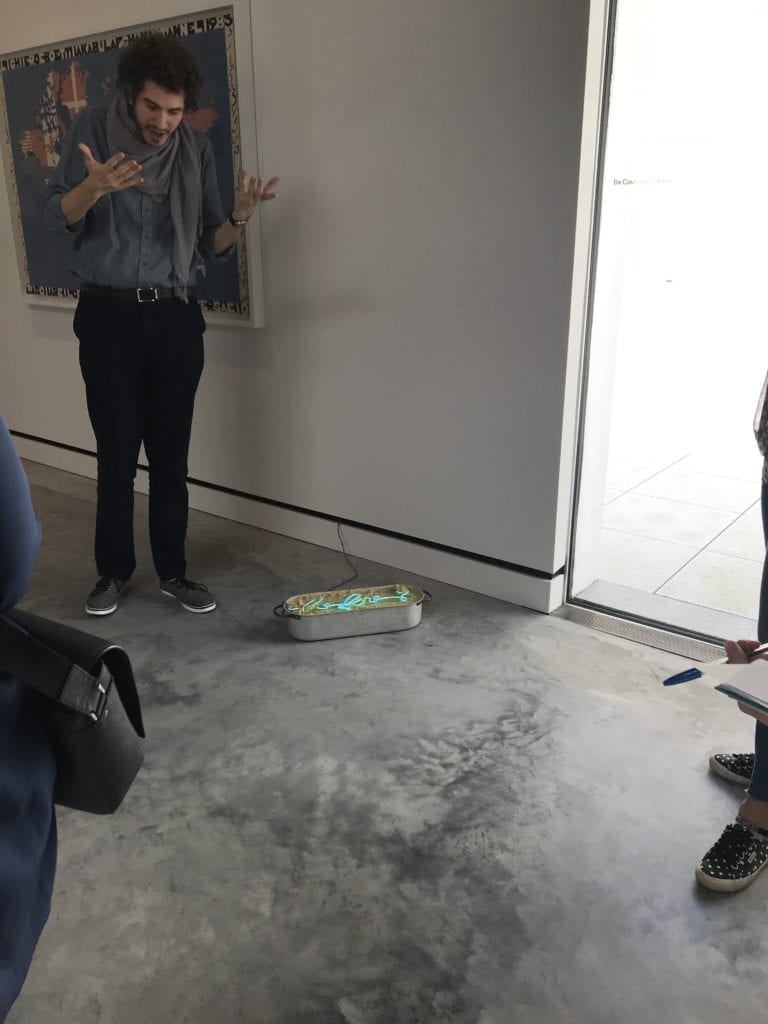

It was then that we were welcomed not only by enticing views into Magazzino’s galleries, but also by two crucial members of the institution’s staff: Director Vittorio Calabrese, as well as Scholar-in Residence (and former CIMA fellow) Francesco Guzzetti, our guide for the afternoon. After relaying a brief account of Magazzino’s history, Calabrese handed over the baton to Guzzetti who launched enthusiastically into a synopsis of Arte Povera: From the Olnick Spanu Collection – the exhibition through which we would soon be navigating – and led us into Gallery 1 to jumpstart his tour.

Arte Povera, we soon learned, is a movement characterized by immense variety, at least where aesthetics are concerned. The artists associated with the movement (i poveristi), are not unified in their approaches to art-making. This condition of variety is presented with particular clarity in Magazzino’s exhibition: the show highlights 12 poveristi – Giovanni Anselmo, Alghiero Boetti, Pierpaolo Calzolari, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascale, Giuseppe Penone, the aforementioned Michelangelo Pistoletto, and Gilberto Zorio – whose works are juxtaposed throughout the warehouse’s galleries, as if to draw attention to their formal differences

Yet, as Guzzetti made clear through his discourse, the objects on display (and, by extension, the authors who conceived them) are far more connected than they initially appear. The poverisiti primarily found common ground in philosophy, a collective mission. During the 1960s – the decade in which their movement technically emerged – all 12 artists were active in Turin, a city in Italy’s northern Piedmont region which, at that time, was transforming into a major industrial center. In the face of this rapid industrialization (and the political upheaval it fomented) the poveristi sought a new mode of artistic expression that was “immediate” and that more aptly reflected the boisterous landscape that surrounded them. Adopting the mantra “Art is Life,” they aimed, in this vein, to eradicate the boundaries between different artistic media, as well as between nature and art.

As suggested, each of the artists in question articulated these views by way of their own artistic language – through distinct styles, subjects, and media. Guzzetti’s tour gave us a taste of each one of these languages. Walking us through the galleries, he did not stop to talk about every work of art on display. Instead, he opted to discuss each artist through the lens of one or two pieces, and, by introducing certain overarching themes, enabled us to understand the ethos uniting them. The first works we observed included Mario Merz’s Che fare? (1967), the mirror paintings of Pistoletto, and Boetti’s Teresa Giancarlo Carlotta Beatrice (1977) and Mappa (1983). In viewing and discussing this diverse grouping, we were introduced to two crucial tendencies in Arte Povera: the use of images and/or materials from everyday life, as well as the integration and involvement of the viewer/the viewer’s space in the display of individual works.

Throughout the remainder of the tour, these habits, among other conceits, emerged continually. A commentary on travel and the transport of goods, Jannis Kounellis’ wall sculpture Bilancino e caffé (2014), for instance, incorporates real coffee grounds, a material that implicates the viewer not only through its unpretentious status as a household staple, but also through its pervasive smell. Giovanni Anselmo’s Particolare (1972-75) likewise demands the involvement of its audience: encompassing a slide projector atop a pedestal, the work seamlessly absorbs its environment into its presentation by projecting the single word in its title onto the wall, as well as any viewer who passes in front of it. Gilberto Zorio’s Stella (1991) combines a large, metal star with a miner’s lamp and a javelin, that similarly (if more aggressively) engages the space of its spectators. Although the work is made of precious materials such as marble, onyx, and gold leaf and, furthermore, bears a title connected to the tradition Greco-Roman myth, Luciano Fabro’s 1997 Eos (L’Aurora) also engages contemporaneity, for, in an effort to invoke issues of sex and sexuality, the artist incorporated condoms into his otherwise lofty composition.

Our afternoon came to a close after observing Giulio Paolini’s Amore e Psiche (1981), a striking work composed of a photo-emulsion on canvas, wood stretches, and colored rayon fabrics. According to Guzzetti, Paolini can very well be considered an outlier among the poveristi group. Relative to his contemporaries, he was ostensibly a far more conceptual artist and explored to a greater extent myth, poetry, and history. Regardless of these idiosyncrasies, Guzzetti deemed Paolini’s masterpiece – based on the story of Cupid and Pysche, as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses – the deal conclusion to our afternoon of art viewing. The work depicts a female form from behind, whose multi-colored garments boldly enter the space of the gallery, evoking the chromatic spectrum. The figure is of course meant to represent the title character of Psyche; however, beyond that she manifests as an analog for her spectators (who look exactly where she looks) and, more broadly, a metaphor for the process of looking, of seeing. By disintegrating the boundaries between viewer and viewed in such a way, the work perfectly encapsulates the mantra central to all Arte Povera: “Art is Life.”