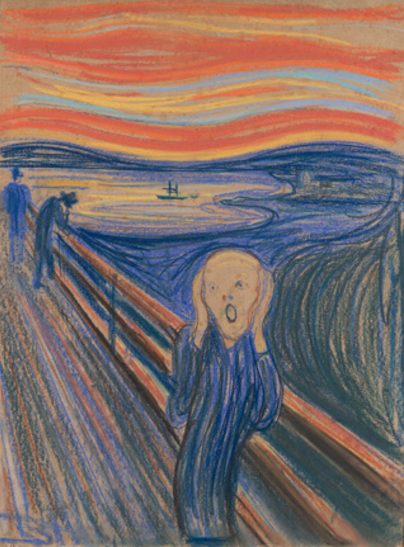

Credit 2016 Edvard Munch/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Private Collection

The Neue Galerie is presenting Munch and Expressionism, an exhibition that explores the mutual influence and intense dialogue between Edvard Munch (1863-1944) and the generation of German-Austrian artists from the early 20th century. Curated by Jill Lloyd, in collaboration with the Munch Museum in Oslo, the exhibition comprises 85 works, including paintings and graphic works, that have never before been shown in New York. The exhibition is divided into four themed rooms, each illustrating a significant aspect of the interaction that arose from the need to express a sense of confusion and disquiet in the face of a growing standardized, alienated, and militaristic capitalist society. Munch’s Self-Portrait with a Skeleton (1895) greets us as a prelude to the exhibition: the disconcerting face of the young artist surfaces from the dark background, his face aged, his gaze lost in space. At the bottom edge of the painting, the arm of a skeleton reminds us of our fleeting existence, a theme which recurs obsessively in the oeuvre of Munch, whose life was scarred by madness and family deaths.

The first room, entitled EXPERIMENTAL PRINTMAKING and dedicated to graphic work and to wood engravings in particular, represents the height of the exchange between the Norwegian painter and the Expressionist Group Die Brücke, which included Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Expressive distortions that border on the grotesque, theatrical gestures, and strong contrasts heightened by acidic, clashing colours are some of most recurring visual elements. The works are displayed in two parallel rows, showcasing the artists’ predilection for serial work, following a practice that was common among contemporary artists such as Claude Monet or Giorgio Morandi (currently on view at the Center for Italian Modern Art). One example is the famous series of Munch’s Madonna (1895/1902), which he realized with different techniques, all united by the iconic portrayal of the female figure, both seductive and evil, an expression of fertility (the swimming sperm depicted on the frame), and death (the skeleton depicted on the bottom edge). Nolde’s Young Danish Woman (1913), marked by the clashing hues of make-up and by the typical rigidity of African idols, is also presented in four variations. At the end of the room a display cabinet contains letters and photos and Gustav’s Schiefler’s monography of Munch’s graphic oeuvre that was very popular among the Expressionists.

The second room, MUNCH AND THE EXPRESSIONISTS IN DIALOGUE, presents several Austrian-German artists’ landscapes and life-sized portraits alongside Munch’s work. In Munch’s Puberty (1894/c. 1915) a nude adolescent is sitting on an unmade bed, her shadow cast on the wall behind her, embodying the anguish of the changes brought on by puberty and the destiny that awaits her of both mother and lover. Girl with a doll (1910) by Heckel contains the same enigmatic ambivalence. A young unclothed woman is lying on a bed, a doll on her knee and a pair of black stockings depicted on her left; here Munch’s theme is revisited, with a clear reference to Manet’s Olympia. Another theme dear to Munch and shared by the Expressionists is of Nature as a safe haven against industrial urbanization, as seen in The Bathers, which is set in an unspoiled environment, and in his other landscapes unmarred by progress. These are intended as landscapes of the soul, like screens on which internal troubles can be projected; they are rendered with flowing brush marks juxtaposed with distorted perspectives and pervaded by a sense of disquiet and deep mysticism. The Blue Gable (1911) by Gabriele Münter, the only female artist in the show, uses the same figurative and expressive language of Munch’s Winter Landscape Elgersburg (1906).

The third room, INFLUENCE AND AFFINITY, readdresses the thematic and expressive affinities in terms of mutual influence and deep consonance with the cultural mood of anguish and introspection ascribed to Expressionism. Kirchner’s Street, Dresden (1908) placed in relation to Munch’s The Book Family, which was exhibited in Dresden in 1906, are examples of spiritual synergy, where the urban environment reflects the sense of disorientation when faced with an anonymous crowd, albeit comprising heavily made-up fashionable female figures. The same feeling of loneliness pervades Munch’s Two Human Beings: The Lonely Ones, in which a man dressed in black and a woman dressed in white, maybe lovers, gaze at the horizon, locked in their inability to communicate; and Separation (1896), which describes the desperation of a man who clutches at his bleeding heart, while a ghostly female figure dressed in white flees in the opposite direction. If for Munch love is often conceived as abandonment or a ghost-like presence, the Viennese painter Egon Schiele represents it in its carnal realism: in Man and Woman (1914), a man and woman lie in a domestic setting, their bodies contorted, their nudity obscene. The space is oppressing with no way of escape. It is framed by a crumpled sheet; the figures are painted from an elevated perspective, which makes the foreshortening extreme. An extraordinary series of self-portraits, another highlight of Expressionism, closes this part of the exhibition. These works by Munch, Richard Gerstl, Ludwig Meidner, and Max Beckmann are depicted with strong colors that are rendered even more dramatic by the shrill tones and the fragmented form that underpins their inner psychological isolation.

It is in the last room, dedicated to Munch’s famous SCREAM, that the autobiographical work is at its most dramatic. The work today is a pop icon of alienation, a manifestation of existential angst, with its skull-like face, the wide eyes, the mouth opened in a cry of pain, the hands covering the eyes as if to display horror at the uproar of the world. The protagonist is the splendid pastel from 1895, which alone is reason enough to see the show. It was inspired by an autobiographical incident, as the caption reads: I was walking along the road with two friends. /The Sun was setting – the Sky turned blood-red. / And I felt a wave of Sadness – I paused tired to Death – Above the blue-black / Fjord and City Blood and Flaming tongues hovered / My friends walked on – I stayed behind – quaking with Angst – I felt the great Scream in Nature. Munch’s pastel is complemented by several of Schiele’s impressive self-portraits from the first decade of the 20th century and Heckel’s etching Man in Pain (1917), in which the upheaval of war becomes a tragic expression of contemporary life.

“Munch and Expressionism” continues through June 13 at the Neue Galerie, 1048 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan; 212-628-6200; neuegalerie.org.